How often do you actually need to pull a pump apart and repair the seal? If you’re relying on a fixed calendar schedule, you’re probably either wasting perfectly good seals or missing failures that develop between intervals. After a decade of field service work across refineries, water treatment plants, and chemical facilities, I’ve found that the answer depends far more on what the seal is telling you than what the calendar says.

The industry standard Mean Time Between Repair (MTBR) for centrifugal pumps sits at 60 months. Top-performing plants push past 100 months. But these numbers mean nothing if you don’t match your maintenance approach to your specific operating conditions.

Typical Maintenance Intervals and MTBR Benchmarks

Most mechanical seals should deliver a minimum of two years of service life. Seals built to API 682 standards target three years or more. In practice, typical plant MTBR ranges from 48 to 76 months depending on application severity and maintenance quality.

These benchmarks give you a baseline, but they’re averages. A seal running in clean, cool water at stable conditions will outlast a seal handling hot slurry by a factor of five or more. The most common mistake I see is plants using a single replacement interval across all their pumps — treating the clean water booster the same as the aggressive chemical transfer pump.

Your actual seal lifespan depends on fluid properties, operating temperature, shaft speed, and how far the pump runs from its best efficiency point. Before setting any schedule, categorize your equipment by severity. A pump that consistently runs 20% away from BEP puts much more stress on the seal than one operating near design point.

Why Time-Based Schedules Fall Short

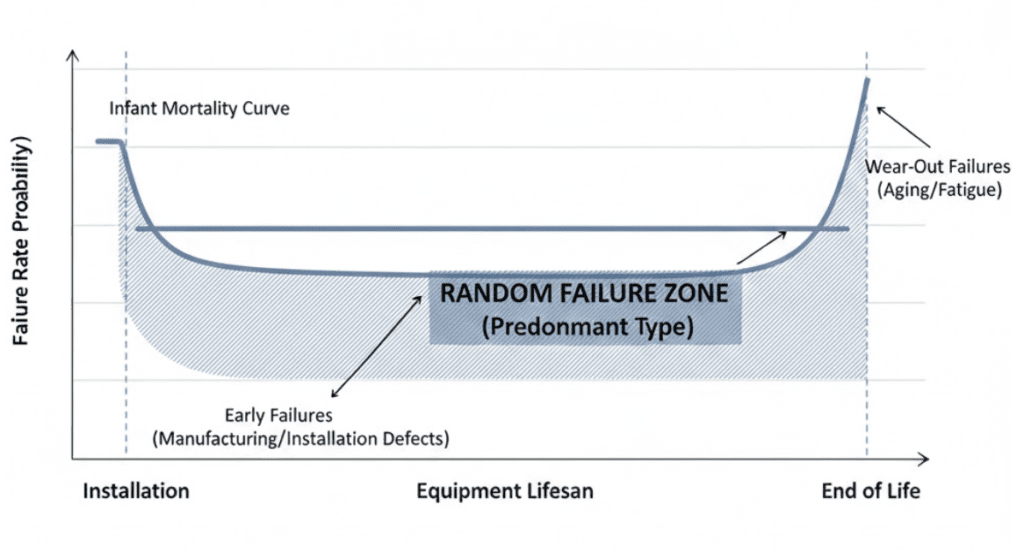

Random failures are the predominant type of mechanical seal failure. Not infant failures from bad installation, not gradual wear-out — random, mid-life failures caused by process upsets, cavitation events, or unexpected contamination.

This single fact undermines fixed replacement schedules. You cannot predict random events with calendar intervals. A seal replaced at 12 months might have lasted another three years. A seal scheduled for replacement at 18 months might fail at month 14 from a process excursion nobody anticipated.

Some operations justify time-based replacement regardless. Pharmaceutical plants often change seals annually whether they need it or not, because contamination risk outweighs the cost of a premature swap. That’s a valid risk management decision for regulated environments, not a maintenance strategy you should copy without the same regulatory pressure.

For everyone else, time-based schedules create two expensive problems. You either replace seals that still have useful life — wasting parts, labor, and introducing the risk of installation errors during unnecessary teardowns. Or you miss failures developing between intervals, turning a manageable repair into catastrophic pump damage that takes out bearings, sleeves, and sometimes the casing itself.

The middle ground is not run-to-failure either. Deliberately running seals until they blow saves on planned maintenance but gambles with secondary damage costs that can exceed the seal cost by ten to twenty times. Condition monitoring is the path between these two extremes.

Condition-Based Monitoring That Works

About 80% of mechanical seal failure root causes trace back to pump operating conditions, not the seal itself. The pump’s flow rate, operating point, temperature, and vibration determine seal fate far more than the seal’s age.

This means monitoring the pump is more important than monitoring the seal. At minimum, track three parameters:

Leakage rate. A sudden increase signals face damage or elastomer degradation. Gradual increases over weeks indicate normal wear approaching end of life. I recommend establishing a baseline leakage rate for each seal shortly after commissioning and tracking deviations. A seal that goes from barely visible weepage to steady dripping has crossed a threshold that demands attention within days, not months.

Temperature. Seal chamber temperature trending upward suggests deteriorating lubrication, inadequate cooling, or process fluid changes. Maintain seal chamber pressure at least 345 kPa (50 psi) above the fluid’s vapor pressure to ensure the faces stay properly lubricated. When that margin erodes, the seal faces can flash the fluid film and run in a semi-dry condition that accelerates wear fast.

Vibration. Overall vibration catches misalignment and bearing problems that kill seals. Be aware that vibration is a lagging indicator — the damage already exists when vibration spikes. Pair it with temperature and leakage trends for earlier warning. Vibration alone is not truly predictive, but combined with the other two parameters, it forms a practical early detection system.

Setting Monitoring Frequency by Criticality

Not every pump deserves the same level of attention. Hindustan Petroleum’s Mumbai Refinery runs a tiered monitoring program across 600 seals: critical equipment gets checked every 10 days, semicritical every three months, noncritical on an as-needed basis.

This frequency-by-criticality approach works because it concentrates resources where failures cost the most. A seal inspection on a critical reactor feed pump justifies frequent cycles. A standby utility pump with a spare on hand can tolerate longer intervals between checks.

Plants running predictive maintenance programs consistently achieve MTBFs of 48 to 80 months. Those are field-verified numbers from programs operating since the mid-1990s. The investment is not exotic sensors — it’s discipline in collecting readings and acting on trends before they become emergencies.

How Application Severity Affects Repair Frequency

Not every seal operates under the same stress. Instead of asking “how often should I repair?” ask “how severe is this application?” and let the answer set your inspection baseline.

Each adverse operating condition compounds multiplicatively against expected seal life. A pump with standard (non-cartridge) seals applies a 0.5 correction factor to the baseline MTBR. Inadequate pressure-temperature margin adds another 0.5 factor. Operating below minimum continuous flow more than 25% of the time adds 0.5. No predictive monitoring program applies a 0.8 factor.

Stack these up: a pump with standard seals, poor PT margin, and no monitoring has an estimated MTBR of 100 x 0.5 x 0.5 x 0.8 = 20 months. That means you should expect to repair that seal roughly every 20 months and set your inspection schedule accordingly — probably monthly checks at minimum.

That same pump with cartridge seals, proper margins, and active monitoring? Expected MTBR jumps to 100 months. One Bay Area refinery achieved exactly that — averaging 100-month MTBR across their rotating equipment by focusing on daily communication between repair teams and engineers, condition monitoring, and proper startup and shutdown protocols. They nearly doubled the API-610 industry standard over five years.

If you skip this step of calculating your expected MTBR, you’ll set intervals that are either wastefully short or dangerously long. Here’s a trick that saves time: calculate the correction factor for each pump criticality class rather than each individual pump. Group similar services together and assign monitoring tiers to the groups.

When evaluating replacement versus repair costs, factor in the true cost of unplanned failures — not just the seal, but lost production, secondary damage to bearings and sleeves, and emergency labor rates that can run triple the normal shop cost.

Making Your Maintenance Schedule Work

Stop asking how often seals need repair on a calendar. Start asking what your seals and pumps are telling you right now. Categorize equipment by severity, set monitoring frequency by criticality, and let condition data — not dates — trigger your repair decisions. The plants achieving 80 to 100 month MTBR aren’t using better seals. They’re watching closer and responding to what the equipment actually needs.