You’re standing in front of a pump with a leaking seal. The old seal has a faded part number stamped on it: “VCFZF” followed by some digits. What does it all mean?

I’ve been there. The first time I needed to order a replacement seal, I stared at those cryptic codes for 20 minutes before calling the supplier. Turns out, those letters and numbers tell you everything you need to know about the seal – if you know how to read them.

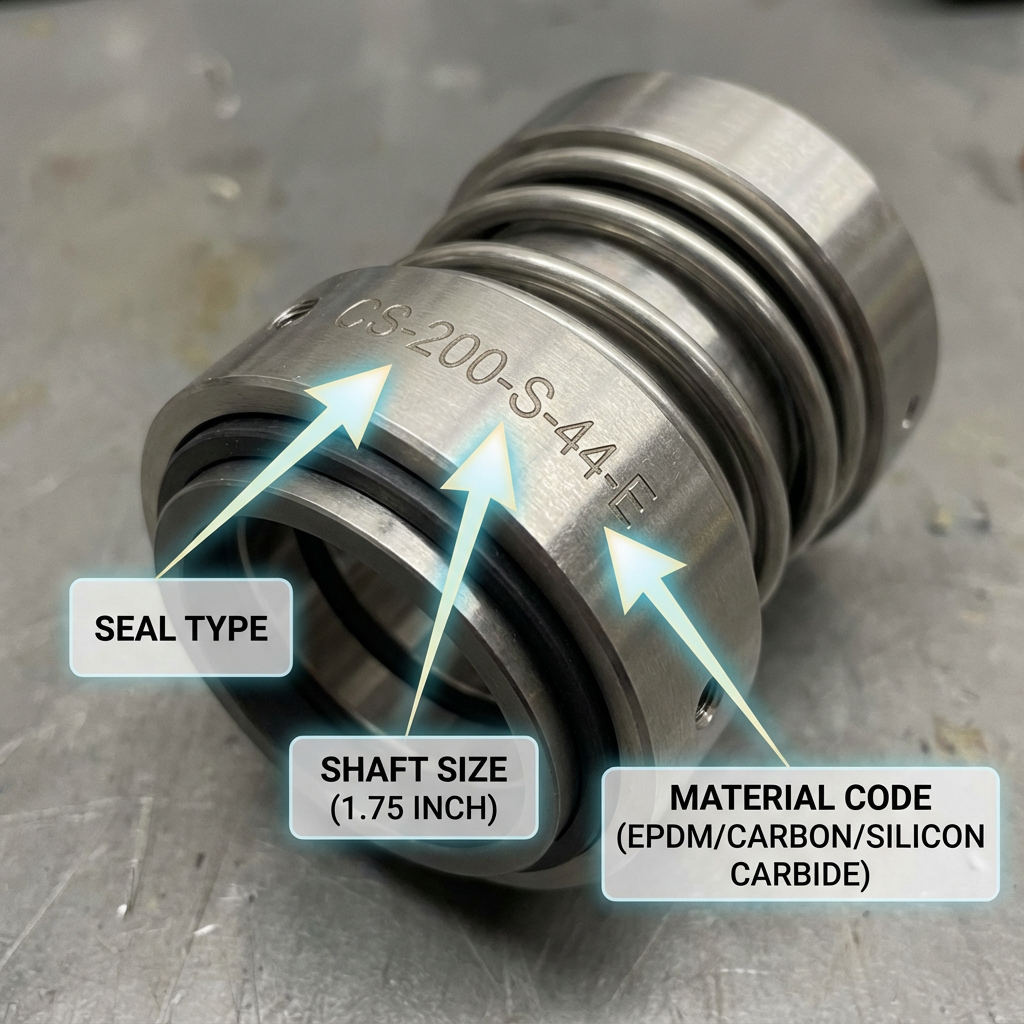

What Information Does a Mechanical Seal Part Number Contain?

A mechanical seal part number packs a lot of information into a short string of characters. Most part numbers include these key elements:

- Seal type or series – Identifies the basic seal design (Type 21, Type 1, MG1, etc.)

- Shaft or sleeve diameter – The size the seal fits

- Material code – Usually 5 characters representing the key component materials

- Configuration indicators – Style, orientation, or special features

- Manufacturer identifiers – Prefixes or suffixes unique to each brand

The most universal piece across manufacturers is the 5-character material code. Master this, and you’ll understand 80% of what any part number tells you.

How Do You Decode the 5-Character Material Code?

The 5-character material code is your Rosetta Stone for mechanical seals. Each position represents a specific component, always in the same order. Let’s decode a common example: BCFZF.

Step 1: Identify the First Character (Elastomer/O-Ring Material)

The first character tells you what the O-rings and gaskets are made of.

In our example, B stands for Buna (also called Nitrile or NBR). This is the most common elastomer in general industrial applications. It handles petroleum-based oils and fuels well, with a temperature limit around 225°F.

Other elastomer codes you’ll see:

- V = Viton (FKM) – Handles chemicals and high temps up to 400°F

- E = EPDM – Great for hot water and steam up to 300°F

- T = PTFE (Teflon) – Nearly universal chemical resistance

- N = Neoprene – General purpose, good weather resistance

Step 2: Identify the Second Character (Rotary Face Material)

The second character identifies the rotating seal face – the part that spins with the shaft.

In BCFZF, the C means Carbon (or Carbon Graphite). This is the workhorse face material. It’s self-lubricating, handles moderate pressures, and works well against harder mating surfaces.

Other rotary face codes:

- L = Silicon Carbide – Harder, handles abrasives better

- Z = Tungsten Carbide – Extremely hard, for severe duty

Carbon faces work great in most water and light chemical applications. For abrasive fluids or high pressures, silicon carbide is usually the better choice.

Step 3: Identify the Third Character (Seal Body Material)

Position three tells you what the seal housing or body is made of.

The F in our code means Stainless Steel (typically 304 or 316). This is standard for most industrial seals and provides good corrosion resistance.

Other body material codes:

- R = 316 Stainless Steel

- G = Cast Iron

- P = Plated Steel

- K = Ni-Resist (for seawater and chloride environments)

Step 4: Identify the Fourth Character (Stationary Face Material)

The fourth position identifies the stationary seat – the fixed component the rotating face runs against.

Z stands for Tungsten Carbide. This extremely hard material pairs well with carbon rotating faces. The hardness difference between carbon and tungsten carbide creates ideal sealing conditions.

Common stationary face codes:

- Z = Tungsten Carbide

- L = Silicon Carbide

- R = Ceramic

- H = Glass-Filled PTFE

Step 5: Identify the Fifth Character (Spring Material)

The final character tells you the spring material.

In BCFZF, the second F again means Stainless Steel. Most springs are stainless for corrosion resistance.

Other spring material codes:

- R = 316 Stainless Steel

- H = Hastelloy (for severe chemical service)

So BCFZF translates to: Buna elastomers, Carbon rotary face, Stainless Steel body, Tungsten Carbide stationary face, Stainless Steel spring. This is one of the most common material combinations for general industrial pump applications.

What Do Common Material Codes Mean?

Here are the quick reference tables I keep at my workstation. Print these out – they’ll save you time.

Elastomer Codes

| Code | Material | Max Temp | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| B | Buna (Nitrile/NBR) | 225°F | Petroleum, oils, hydraulic fluids |

| V | Viton (FKM) | 400°F | Chemicals, fuels, high temp |

| E | EPDM | 300°F | Hot water, steam, ketones, alcohols |

| T | PTFE | 500°F | Nearly all chemicals |

| N | Neoprene | 200°F | Refrigerants, moderate chemicals |

| Y | Kalrez | 600°F | Extreme chemical resistance |

Face Material Codes

| Code | Material | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| C | Carbon/Graphite | Self-lubricating, standard duty |

| L | Silicon Carbide | Hard, abrasion resistant |

| Z | Tungsten Carbide | Extremely hard, severe duty |

| H | Glass-Filled PTFE | Chemical resistant, lower cost |

| R | Ceramic | Economical, moderate duty |

Metal Component Codes

| Code | Material | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|

| F | Stainless Steel (304/316) | Standard industrial |

| R | 316 Stainless Steel | Better corrosion resistance |

| P | Plated Steel | Economy applications |

| G | Cast Iron | Heavy duty, non-corrosive |

| K | Ni-Resist | Seawater, chlorides |

| S | Tool Steel | High wear applications |

How Do You Read Shaft Size in a Part Number?

Shaft size encoding varies by manufacturer, but there’s a common system you’ll encounter on many seals.

Step 1: Identify the Unit System Indicator

Look for a letter at the start of the size portion:

- E = English (inches)

- M = Metric (millimeters)

Step 2: Decode the Diameter Digits

For English (inch) sizes, you’ll typically see 6 digits:

- First 3 digits = whole inches

- Last 3 digits = decimal portion

Example: E001500 means 1.500 inches (1-1/2″)

For Metric sizes:

- First 4 digits = whole millimeters

- Last 2 digits = decimal portion

Example: M003800 means 38.00 mm

Some manufacturers simplify this. You might see “1.500” or “38mm” directly in the part number. John Crane’s Type 21 seals, for instance, often include the shaft size as a simple decimal: T21-1.500 means a Type 21 seal for a 1.500″ shaft.

Pro tip: When in doubt, grab your calipers and measure the shaft. The part number tells you the intended size, but the actual shaft might have wear. I’ve seen shafts worn 0.002″ undersized that caused seal leaks on brand new seals.

How Do Major Manufacturers Structure Their Part Numbers?

Each manufacturer has their own system. Here’s what you’ll encounter from the big names.

John Crane Part Numbers

John Crane uses a type numbering system that’s become an industry standard. Their most common seals:

- Type 21 – Elastomer bellows seal, the most widely used OEM seal

- Type 1 – Metal bellows seal for demanding applications

- Type 5610 – Cartridge seal for ANSI pumps

A typical John Crane part number might look like: T21-1.750-BCFZF

This breaks down as:

- T21 = Type 21 seal

- 1.750 = 1-3/4″ shaft size

- BCFZF = Material code

John Crane also uses working length designations:

- L3 = Standard working length

- L3* = DIN L1K standard (seat not included)

- L3** = DIN L1N standard (seat not included)

Flowserve Part Numbers

Flowserve uses several formats depending on the product line:

- Numeric format: 21-050-04 (Type 21, specific size and configuration)

- Alphanumeric: A2R14569-01 (catalog reference number)

- OEM numbers: 75630517

The Pac-Seal line from Flowserve uses standard material codes similar to what we covered above.

Other Manufacturers (Burgmann, AESSEAL, Chesterton)

Here’s a quick reference for common model designations:

EagleBurgmann:

- MG1, MG12 – Standard component seals

- M2N, M3N, M7N – Various configurations

- H12N – Heavy duty

- BT-RN, BT-FN – Bellows types

AESSEAL:

- B02, B012 – Common replacement models

- P04, P04T – Equivalent to Type 21

Chesterton:

- 891 – Rotary single inside seal

- 1810 – Heavy duty cartridge seal

These manufacturers often cross-reference to John Crane types. A Type 21 equivalent exists in almost every brand’s catalog.

What If the Part Number Is Worn or Missing?

Old seals often have illegible markings. Here’s how to identify a seal without a readable part number.

Step 1: Measure the Shaft/Sleeve Diameter

Remove the seal from the shaft. On the back of the seal head (the end that faces the spring), measure the inside diameter with calipers.

This gives you the shaft size the seal was designed for. Add about 0.016″ to account for the interference fit on the elastomer.

Step 2: Measure the Seal Head Dimensions

Measure the outside diameter of the seal head assembly. This tells you if the seal will fit in your stuffing box bore.

Also measure the inside diameter of the seal head where it contacts the shaft or sleeve.

Step 3: Measure the Stationary Seat

Take three measurements on the seat:

- Inside diameter (bore)

- Outside diameter

- Thickness (including any gasket)

The OD is especially important – subtract 0.010″ to 0.020″ from the measured bore to account for the rubber squeeze fit.

Step 4: Identify the Materials Visually

Look at the elastomers:

- Black rubber that’s soft and flexible = likely Buna

- Brown or tan rubber = often Viton

- Gray or white = possibly EPDM or PTFE

Check the seal faces:

- Dark gray/black with a slight sheen = Carbon

- Very hard, light gray = Silicon Carbide or Tungsten Carbide

- White or off-white = Ceramic

Step 5: Use a Cross-Reference Chart

With your measurements in hand, use a dimensional cross-reference chart. US Seal Manufacturing publishes a detailed “Cross Reference by Shaft Size” guide that matches dimensions to part numbers.

Start with the shaft size column, then match the seal head OD, operating height, and seat dimensions. This narrows down the options to one or two possible seals.

If you’re still stuck, email a photo and your measurements to a seal supplier. Most can identify the seal from pictures and dimensions, even when the markings are completely gone.

What Common Mistakes Should You Avoid When Reading Part Numbers?

I’ve seen these errors trip up even experienced technicians:

- Confusing similar manufacturer codes – A “Type 21” from John Crane isn’t identical to Flowserve’s “21 series.” Cross-reference carefully.

- Misreading inches vs. millimeters – A 1.500″ seal and a 38mm seal look similar on paper but won’t interchange properly. Always verify the unit system.

- Ignoring material compatibility – That EPDM seal looks identical to the Buna one, but it’ll swell up and fail in petroleum service. Match materials to your fluid.

- Using outdated cross-reference charts – Manufacturers update their product lines. A chart from 2010 might reference discontinued seals. Use current resources.

- Assuming universal coding – Not all manufacturers use the same letter codes. Some use “V” for Viton, others use “F” for Fluoroelastomer (same material). Check manufacturer-specific documentation.

Putting It All Together

Reading mechanical seal part numbers is straightforward once you understand the pattern. The 5-character material code (elastomer, rotary face, body, stationary face, spring) is consistent across most manufacturers. Shaft sizes follow logical numeric patterns. Seal types and configurations vary by brand, but cross-reference resources make translation easy.

When you can’t read the part number, measure everything and work backwards. Shaft diameter, seal head dimensions, and seat measurements will get you to the right replacement.

Keep a material code reference chart at your workstation. Bookmark the cross-reference resources from US Seal, Springer Pumps, and All Seals. Next time you need to decode a part number, you’ll have the answer in minutes instead of hours.