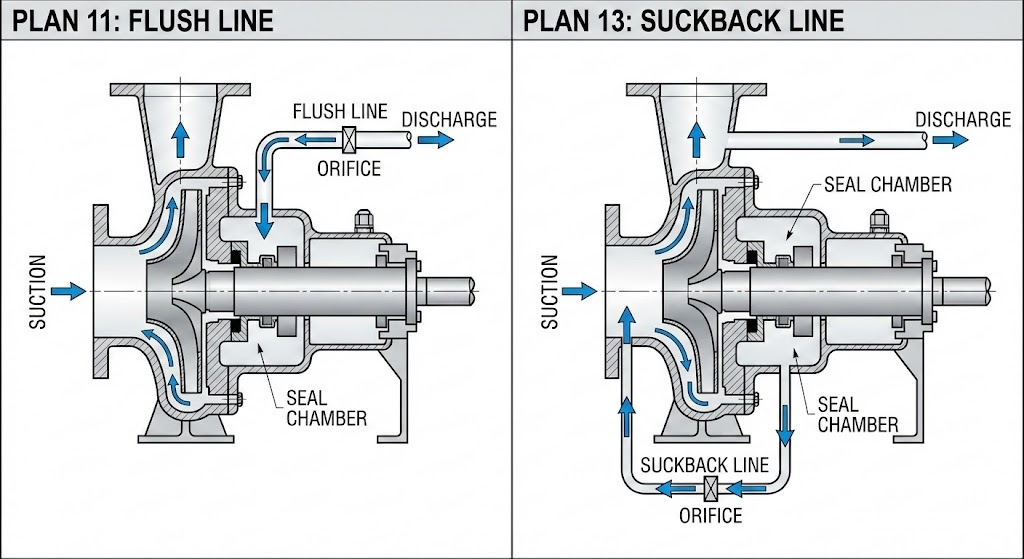

The fundamental difference between these two piping plans comes down to pressure direction. A flush line (Plan API 11) increases cámara del sello pressure to 100% of discharge pressure. A suckback line (Plan API 13) reduces it to equal suction pressure. This pressure difference fundamentally changes seal behavior and determines which applications each plan suits.

This comparison will give you a clear decision framework for selecting the right plan, complete with specifications, troubleshooting guidance, and a straightforward selection matrix.

What Is the Functional Difference Between a Flush Line and a Suckback Line?

The core difference is flow direction and its effect on stuffing box pressure in a mechanical seal. A flush line pushes fluid into the seal chamber from discharge. A suckback line pulls fluid out of the seal chamber toward suction.

Flush Line (API Plan 11): Flow from Discharge to Seal Chamber

A flush line routes high-pressure fluid from the pump discharge through an orifice and into the seal chamber. The flow direction is: Discharge to Orifice to Seal chamber to Back into pump.

This arrangement increases stuffing box pressure to 100% of discharge pressure. The primary purposes include flushing debris away from seal faces, cooling the seal, and maintaining adequate vapor pressure margin. Plan API 11 remains the default choice for most applications because it accomplishes multiple objectives with simple piping.

The orifice controls flow rate by creating a pressure drop between discharge and the seal chamber. For most horizontal pump applications, I recommend Plan 11 as your starting point – it covers 50-75% of all seal applications for good reason.

Suckback Line (API Plan 13): Flow from Seal Chamber to Suction

A suckback line works in reverse. Fluid flows from the seal chamber through an orifice back to pump suction. The flow direction is: Seal chamber to Orifice to Pump suction.

This arrangement reduces stuffing box pressure to equal suction pressure. The primary purposes include relieving excessive seal chamber pressure, providing self-venting capability, and removing vapor from vertical pump configurations. Plan API 13 is sometimes called a “reverse flush” because of this opposite flow direction.

The orifice in Plan 13 creates backpressure rather than controlling inlet flow. This distinction matters for sizing calculations.

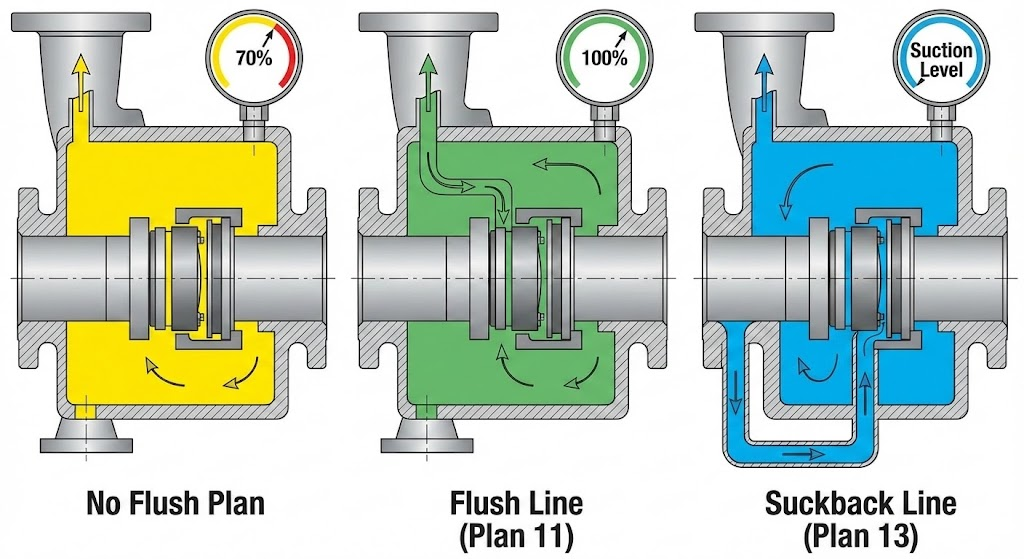

The Pressure Rule: 70% / 100% / Suction

Understanding the pressure effects provides a clear mental model for selection decisions. The table below shows how each configuration affects seal chamber pressure.

| Configuration | Stuffing Box Pressure |

|---|---|

| No plan de lavado | Approximately 70% of discharge pressure |

| With flush line (Plan 11) | 100% of discharge pressure |

| With suckback line (Plan 13) | Equal to suction pressure |

This 70/100/suction rule provides the foundation for understanding when each plan applies. If you need higher pressure at the seal, use a flush line. If you need lower pressure, use a suckback line.

When Should You Use a Flush Line vs a Suckback Line?

Selection depends primarily on pump orientation and pressure requirements. Horizontal pumps generally favor Plan 11. Vertical pumps typically require Plan 13 or Plan 14.

Choose Flush Line (Plan 11) When:

Plan 11 should be your default consideration for the following situations:

- Horizontal pump applications with standard configurations

- Clean, non-polymerizing fluids that won’t clog the orifice

- Applications requiring increased seal chamber pressure

- Sufficient differential pressure exists between discharge and seal chamber

- Hydrocarbon service under 150 degrees Celsius with satisfactory vapor pressure margin

The key advantage of Plan 11 is more efficient heat removal compared to Plan 13. The higher pressure also increases vapor pressure margin, which prevents the pumped fluid from flashing at the seal faces.

Choose Suckback Line (Plan 13) When:

Plan 13 becomes the better choice in specific circumstances:

- Vertical pumps without a bleed bush installed below the seal chamber

- High-head horizontal pumps where Plan 11 cannot provide adequate flow

- Applications requiring pressure reduction at the seal

- High differential pressure situations that would require multiple orifices with Plan 11

Vertical pumps should use Plan 13 or Plan 14. Plan 11 alone cannot provide adequate venting in vertical configurations because vapor tends to collect at the top of the seal chamber with no escape path.

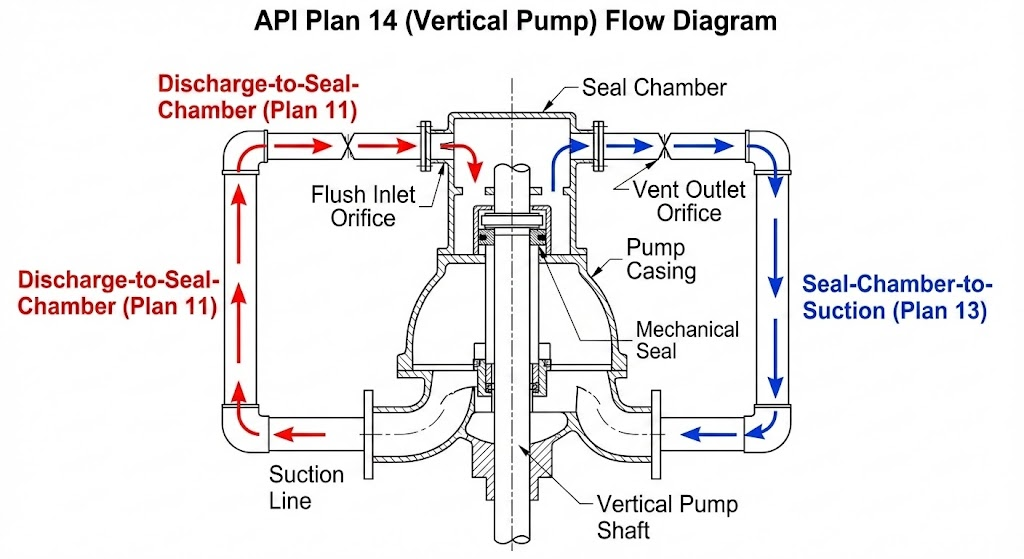

What About Plan 14? The Combination Approach

Plan 14 combines Plan 11 and Plan 13 simultaneously. Flow recirculates from the pump discharge into the seal chamber while also flowing from the seal chamber to the pump suction.

This combination is most commonly used on vertical pumps. Plan 14 provides adequate flush flow, continuous venting capability, and improved vapor pressure margin – addressing limitations that either plan has individually.

Consider Plan 14 for viscous products where the buje de garganta restricts flow, light hydrocarbons subject to flashing, or any vertical pump application where single plans prove inadequate.

What Are the Advantages and Disadvantages of Each Approach?

Each plan involves trade-offs. The comparison table below summarizes the key differences for decision-making.

Comparison Table: Flush Line vs Suckback Line

| Factor | Flush Line (Plan 11) | Suckback Line (Plan 13) |

|---|---|---|

| Heat removal | More efficient | Less efficient |

| Autoventilación | Sí (bombas horizontales) | Sí (mejor para bombas verticales) |

| Efecto de presión | Aumenta la presión de la cámara | Reduce la presión de la cámara |

| Mejor para | Bombas horizontales, servicio general | Bombas verticales, alta carga |

| Control de flujo | El orificio controla el flujo | El orificio genera contrapresión |

| Complejidad | Simple, el más común | Estándar para aplicaciones específicas |

| Uso en el mercado | 50-75% de todas las aplicaciones de sellado | Aplicaciones especializadas |

El Plan 11 domina el mercado porque maneja efectivamente la mayoría de los escenarios de bombeo comunes. Sin embargo, forzar el Plan 11 en aplicaciones de bombas verticales es un error que veo con frecuencia.

Limitaciones a considerar

Limitaciones de la línea de lavado (Plan 11):

- Evitar con medios que contengan sólidos, abrasivos o sustancias polimerizantes

- No recomendado cuando la presión diferencial entre la descarga y la cámara del sello es demasiado baja

- El orificio puede obstruirse con fluidos contaminados

- Sin capacidad de ventilación de vapores en configuraciones de bombas verticales

Limitaciones de la línea de retorno por succión (Plan 13):

- Refrigeración menos eficiente, requiere mayores caudales para compensar

- Puede necesitarse un control de flujo complejo para altas presiones diferenciales

- No es adecuado cuando la presión de la cámara del sello es muy cercana a la presión de succión

- Bajo flujo si la presión diferencial es mínima

¿Qué caudales y límites de temperatura se aplican?

Un dimensionamiento correcto previene tanto el enfriamiento insuficiente como la erosión excesiva. Las siguientes pautas se aplican tanto a configuraciones de lavado como de retorno por succión.

Pautas de caudal

La regla general de la industria es 1 GPM por pulgada de tamaño del sello. Para un sello de 2 pulgadas, planifique aproximadamente 2 GPM de flujo de lavado.

Los servicios con vaporización requieren el doble de la tasa estándar: 2 GPM por pulgada de tamaño del sello. El flujo adicional compensa el calor absorbido durante la vaporización.

Todos los orificios deben tener un diámetro mínimo de 3 mm (1/8 de pulgada). El Plan 13 típicamente utiliza un orificio mayor de 6 mm (1/4 de pulgada) para ventilar vapores efectivamente.

Para cálculos detallados, consulte la guía sobre cómo calcular el caudal de lavado para sellos mecánicos.

Límites de aumento de temperatura

La temperatura de las caras del sello debe mantenerse dentro de límites aceptables para prevenir el desgaste prematuro. El aumento máximo de temperatura permitido varía según el tipo de fluido.

| Tipo de Fluido | Aumento Máximo de Temperatura |

|---|---|

| Agua | 15 grados Fahrenheit |

| Hidrocarburos ligeros | 5 grados Fahrenheit |

| Aceites lubricantes | 30 grados Fahrenheit |

Estos límites explican por qué los servicios con hidrocarburos requieren atención particular. Un sello mecánico puede experimentar choque térmico y fracturarse en 30 segundos de funcionamiento en seco – haciendo que un flujo de lavado adecuado sea crítico.

El margen de presión de vapor debe ser aproximadamente 50 psi por encima de la presión de vapor para evitar la vaporización en las caras del sello. Si su plan de lavado no puede mantener este margen, considere actualizar a Plan 23 con un enfriador o al Plan 32 con una fluido de lavado externo fuente externa.