Your pumps are failing again. The maintenance team just pulled another seal, and the faces show the telltale signs of heat damage. Sound familiar?

Here’s what most plant managers don’t realize: getting the flush flow rate wrong is one of the biggest reasons mechanical seals fail prematurely. Too little flow and your seal overheats. Too much flow and you’re eroding components while burning through your operating budget.

Calculating the right flush flow rate isn’t complicated once you know the method.

Start with 1 GPM per inch of seal size for standard services. For flashing hydrocarbons, double it to 2 GPM per inch. But that’s just the starting point.

What Information Do You Need Before Calculating Flush Flow Rate?

You need six key pieces of data before running any flush flow calculation: seal size, pump speed, seal chamber pressure, fluid properties, operating temperature, and your flush plan type.

What Data Should You Gather First?

Grab these numbers from your pump datasheet or measure them directly:

- Seal size – The nominal seal diameter in inches. If you can’t find this, use the shaft diameter as a close approximation.

- Pump operating speed – Usually 1800 or 3600 RPM for most industrial pumps. Higher speeds generate more heat.

- Seal chamber pressure – This determines how much differential pressure your flush system works against. Typical estimate: 80% of discharge pressure plus suction pressure.

- Process fluid properties – You’ll need specific heat capacity, density, and vapor pressure for detailed calculations.

- Process fluid temperature – Critical for determining how close you are to the vapor pressure limit.

- Flush plan type – Different plans require different calculation approaches.

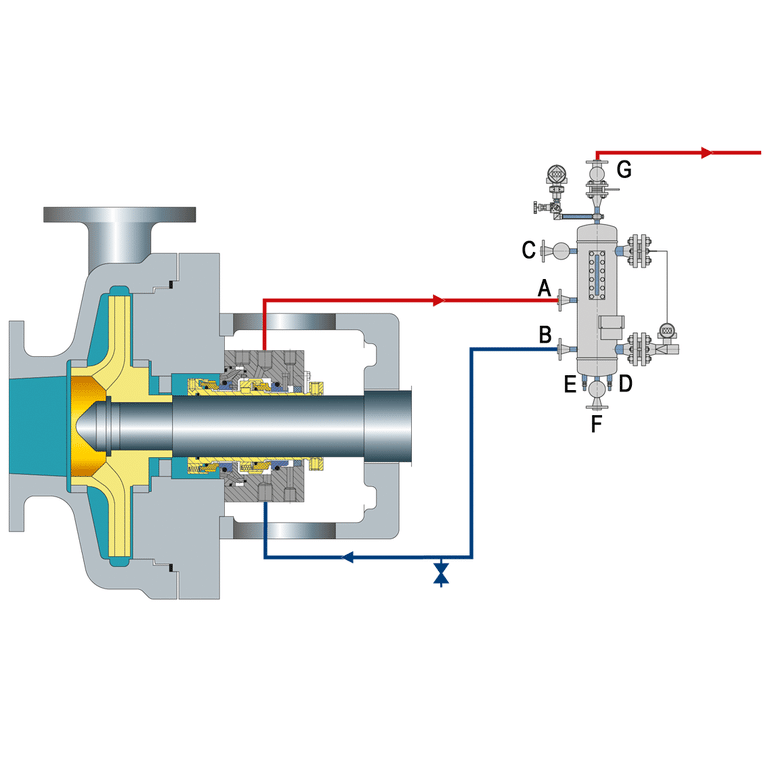

Which Flush Plan Are You Using?

Your flush plan determines which calculation method applies. Here’s a quick reference:

| Flush Plan | Description | Best For | Calculation Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plan 11 | Discharge bypass through orifice | Clean fluids, standard services | Orifice sizing, recirculation rate |

| Plan 21 | Single-pass with cooler | High-temperature services | Heat removal capacity |

| Plan 23 | Closed loop with cooler | Hot services, limited cooling water | Heat exchanger sizing |

| Plan 32 | External flush injection | Dirty, abrasive, or contaminated fluids | Throat bushing velocity |

Plan 11 handles over 50% of all seal installations. It’s the default choice for clean services where the process fluid can lubricate and cool the seal. Plan 32 is your go-to when the process fluid contains solids or contaminants that would damage the seal.

How Do You Calculate Flush Flow Rate Using the Rule of Thumb Method?

The rule of thumb method gives you a reliable flush flow rate in under a minute. It works for most standard applications running below 3600 RPM and 500 psig.

Step 1: Measure Your Seal Size

Find the seal size on your pump datasheet or seal documentation. It’s usually listed as the nominal shaft diameter at the seal location.

Can’t find it? Measure the shaft diameter where the seal mounts. A 2-inch shaft typically uses a 2-inch seal. For between-bearing pumps, measure at each seal location.

Pro tip: Most single-stage process pumps use seals between 1.5 and 4 inches. Larger pumps might run up to 6 inches or more.

Step 2: Apply the Basic Formula

For standard services (water, clean hydrocarbons, non-flashing liquids):

Flush Rate (GPM) = Seal Size (inches) × 1.0

For flashing services (light hydrocarbons near their boiling point):

Flush Rate (GPM) = Seal Size (inches) × 2.0

Example: You’ve got a 3-inch seal pumping cooling water at 150°F.

- Standard formula: 3 inches × 1.0 = 3 GPM

Same pump, but now you’re handling propane at elevated temperature:

- Flashing formula: 3 inches × 2.0 = 6 GPM

The simplest approach? Just use 2 GPM as a baseline for any standard application. This works for the vast majority of refinery and chemical plant pumps.

Step 3: Adjust for Operating Conditions

The rule of thumb assumes typical operating conditions. Adjust upward when:

- Speed exceeds 3600 RPM – Higher speeds generate more friction heat

- Seal chamber pressure exceeds 500 psig (35 bar) – Higher pressures mean more face loading and heat

- Fluid has poor heat capacity – Some fluids don’t absorb heat as efficiently

You might get away with less flow when:

- Speed is below 1800 RPM – Less friction, less heat

- Service is clean and cool – Clean water at ambient temperature, for instance

- Application is non-critical – Some low-flow applications run fine at 0.25-0.5 GPM

I’ve seen plants run small utility pumps at minimal flush rates for years without issues. But for anything critical? Stick with the rule of thumb minimum.

How Do You Calculate Flush Flow Rate Using the Temperature Rise Method?

The temperature rise method calculates exactly how much flow you need to remove the heat generated by your seal. It’s more precise than the rule of thumb but requires more data.

Step 1: Determine Your Allowable Temperature Rise

Different fluids tolerate different amounts of heating before problems start. Use these limits:

| Fluid Type | Maximum Temperature Rise | Why This Limit? |

|---|---|---|

| Light hydrocarbons (propane, butane) | 5°F (2.8°C) | Close to boiling point, flashing risk |

| Water | 15°F (8.3°C) | Good heat capacity, stable |

| Oils and heavy hydrocarbons | 30°F (16.7°C) | High boiling point, viscosity concerns |

These aren’t arbitrary numbers. They represent the point where fluid properties start degrading or you risk flashing at the seal faces.

Step 2: Estimate Heat Generated by the Seal

The seal faces generate heat through friction and fluid shear. The basic formula:

Q = μ × P × V × A

Where:

- Q = Heat generated

- μ = Friction coefficient (typically 0.05-0.1 for lubricated seals)

- P = Face pressure

- V = Surface velocity at the seal face

- A = Face contact area

That looks complicated. Here’s the shortcut: ask your seal manufacturer.

Seal vendors calculate heat generation for every application. It’s part of their selection process. For a typical balanced seal running at 3600 RPM, expect heat generation between 500 and 2000 BTU/hr depending on size and face loading.

If you need a rough estimate without manufacturer data, most seals generate about 300-500 BTU/hr per inch of seal size at 3600 RPM.

Step 3: Calculate the Required Flow Rate

Once you know heat generation and allowable temperature rise:

Flow Rate (GPM) = Heat Generated (BTU/hr) ÷ (500 × ΔT × Specific Gravity)

The “500” factor converts the units for water-like fluids. For other fluids, adjust based on specific heat capacity.

Example: Your seal generates 1,200 BTU/hr. You’re sealing water with an allowable ΔT of 15°F.

Flow Rate = 1,200 ÷ (500 × 15 × 1.0) = 1,200 ÷ 7,500 = 0.16 GPM

That seems low, right? That’s because water has excellent heat capacity.

Step 4: Compare with Rule of Thumb and Use the Higher Value

Here’s the critical step most people skip. Always take the larger of:

- Your calculated minimum flow rate

- The rule of thumb rate (1 GPM per inch of seal size)

Example continued: For a 2-inch seal:

- Calculated minimum: 0.16 GPM

- Rule of thumb: 2.0 GPM

- Use: 2.0 GPM

Why? The rule of thumb accounts for factors beyond pure heat removal—like flushing debris, providing margin for process upsets, and compensating for fouled coolers.

For that propane application with a 5°F limit? Your calculated flow will likely exceed the rule of thumb. In that case, use the calculated value plus some margin.

How Do You Calculate Flush Flow Rate for API Plan 32 (External Flush)?

Plan 32 injects clean flush fluid from an external source to keep contaminants away from the seal. The calculation focuses on throat bushing velocity rather than just heat removal.

Step 1: Determine Target Throat Bushing Velocity

The industry standard target is 15 feet per second (fps) velocity across the throat bushing.

Why 15 fps? At this velocity, the flush creates enough flow to sweep process fluid away from the seal faces. Lower velocities let contaminants migrate toward the seal. Higher velocities can cause erosion.

For particularly dirty or abrasive services, some engineers push to 20-25 fps. But 15 fps handles most applications.

Step 2: Calculate the Bushing Annular Area

The throat bushing creates an annular gap between the bushing bore and the shaft. You need this area for the flow calculation.

Annular Area = π × (D²bushing – D²shaft) ÷ 4

Example: Your throat bushing has a 2.010-inch bore, and your shaft is 2.000 inches.

- Bushing bore: 2.010 inches

- Shaft diameter: 2.000 inches

- Diametrical clearance: 0.010 inches

Area = π × (2.010² – 2.000²) ÷ 4

Area = 3.14159 × (4.040 – 4.000) ÷ 4

Area = 3.14159 × 0.040 ÷ 4

Area = 0.0314 square inches

Can’t find exact dimensions? API 682 specifies typical clearances. For pumps per API 610, expect 0.010-0.015 inch diametrical clearance.

Step 3: Calculate Required Flow Rate

With velocity target and area known:

Flow Rate (GPM) = Velocity (fps) × Area (sq in) × 60 ÷ 231

The 60 converts seconds to minutes. The 231 converts cubic inches to gallons.

Example continued:

Flow Rate = 15 × 0.0314 × 60 ÷ 231

Flow Rate = 28.26 ÷ 231

Flow Rate = 0.12 GPM

Wait, that seems low. Let’s check with the rule of thumb: 1 GPM per inch of seal size gives us 2 GPM for a 2-inch seal.

Here’s the catch—the velocity calculation gives minimum flow to maintain the velocity barrier. Most plants use 3-5 GPM per seal for Plan 32 systems to provide adequate margin.

Step 4: Set Flush Pressure

Your flush must overcome the seal chamber pressure plus provide velocity across the bushing:

Target flush pressure: 10-15 psi above seal chamber pressure

For critical applications or services where even small amounts of process contamination are unacceptable, push to 20-25 psi above.

One more thing: the flush must be compatible with your process fluid. You’re injecting this flush directly into the pump. Water is the most common choice, but some applications need specific solvents or clean product.

How Do You Size the Orifice for Your Flush System?

The orifice controls your flow rate. Size it wrong, and your carefully calculated flush rate becomes meaningless.

Step 1: Know Your Pressure Differential

Calculate the pressure drop available across your orifice:

ΔP = Source Pressure – Seal Chamber Pressure

For Plan 11 systems:

ΔP = Pump Discharge Pressure – Seal Chamber Pressure

Typical seal chamber pressure runs about 80% of discharge pressure plus suction. So if your pump develops 200 psig discharge with 20 psig suction:

Seal chamber pressure ≈ (0.80 × 200) + 20 = 180 psig

ΔP available = 200 – 180 = 20 psi

That’s not much. It’s why Plan 11 orifices tend to be small—you don’t have much driving force.

Step 2: Select Minimum Orifice Size

Never go smaller than 1/8 inch (3 mm) orifice diameter unless your process is exceptionally clean.

Why? Smaller orifices plug. When your orifice clogs, your seal gets no flush. Game over.

Standard orifice sizes by plan:

| Flush Plan | Typical Orifice Size | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Plan 11 | 1/8″ (3 mm) | Most common, clean services only |

| Plan 13 | 1/4″ (6 mm) | Larger to allow vapor venting |

| Plan 21 | 1/8″-1/4″ | Depends on cooler pressure drop |

| Plan 32 | No orifice | Flow meter or valve for control |

Step 3: Calculate Orifice Size for Target Flow Rate

For cases where you need a specific size, the orifice flow equation:

Q = Cd × A × √(2 × ΔP ÷ ρ)

Where:

- Q = Flow rate

- Cd = Discharge coefficient (typically 0.6-0.65)

- A = Orifice area

- ΔP = Pressure differential

- ρ = Fluid density

In practice, you’ll find that a 1/8-inch orifice delivers 2-3 GPM at 100 psi differential. That’s enough for most applications.

When standard orifices won’t work:

High differential pressure creates a problem. A single 1/8-inch orifice with 500 psi differential could deliver 6+ GPM—way more than you want.

Solutions:

- Multiple orifices in series – Mount them at least 6 inches apart

- Choke tube – A length of small-bore tubing that creates distributed pressure drop

- Flow control valve – More expensive but adjustable

I prefer the choke tube approach for high-pressure applications. It’s simple, reliable, and won’t plug like a tiny orifice would.

Quick Reference: Flush Flow Rate Calculation Summary

Here’s everything in one place for quick field reference.

Calculation Methods at a Glance

| Method | When to Use | Formula | Typical Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rule of Thumb | Standard services, <3600 RPM, <500 psig | GPM = Seal Size (in) × 1.0 | 1-4 GPM |

| Flashing Services | Light hydrocarbons near boiling | GPM = Seal Size (in) × 2.0 | 2-8 GPM |

| Temperature Rise | Critical applications, unusual fluids | Q ÷ (500 × ΔT × SG) | Varies |

| Throat Bushing Velocity | Plan 32 external flush | V × A × 60 ÷ 231 | 3-5 GPM |

Quick Decision Guide

Is your application standard or special?

Standard application (use rule of thumb):

- Clean fluid

- Speed ≤3600 RPM

- Pressure ≤500 psig

- Plan 11 or Plan 23

- Non-critical service

Special application (run detailed calculations):

- Dirty, abrasive, or contaminated fluid

- Speed >3600 RPM

- Pressure >500 psig

- Volatile/flashing hydrocarbons

- Plan 32 external flush

- Critical service where failure causes significant impact

Key Numbers to Remember

- Minimum orifice size: 1/8 inch (3 mm)

- Target throat bushing velocity: 15 fps

- Flush pressure above seal chamber: 10-15 psi (25 psi for critical)

- Temperature rise limits: 5°F (light HC), 15°F (water), 30°F (oils)

- Best practice: Use the LARGER of calculated or rule-of-thumb value

Conclusion

Calculating flush flow rate comes down to a simple process: start with the rule of thumb (1 GPM per inch of seal size), then verify with detailed calculations for anything critical or unusual.

The right flow rate balances two competing goals. Too low, and you’re cooking your seals. Too high, and you’re wasting money and potentially eroding components.

Three things to do now:

- Check your current flush rates – Are they documented? Do they match the calculations?

- Install monitoring – At minimum, track seal chamber temperature. It’s the earliest warning of insufficient cooling.

- Review after failures – Every seal failure is an opportunity to validate or adjust your flush rates.

The math isn’t complicated. The discipline to calculate, verify, and monitor makes the difference between seals that last months and seals that last years.