A mechanical seal quench system might not be something you think about every day, but if you’re running industrial equipment with hazardous or high-temperature fluids, this system is critical for preventing costly failures and keeping your operations safe.

A quench system introduces a secondary fluid—typically steam, water, or nitrogen—to the atmospheric side of a mechanical seal to cool it, prevent contamination, and protect against leakage. By the time you finish reading this guide, you’ll understand what a quench system does and how to install one properly.

Quench System Components and Types

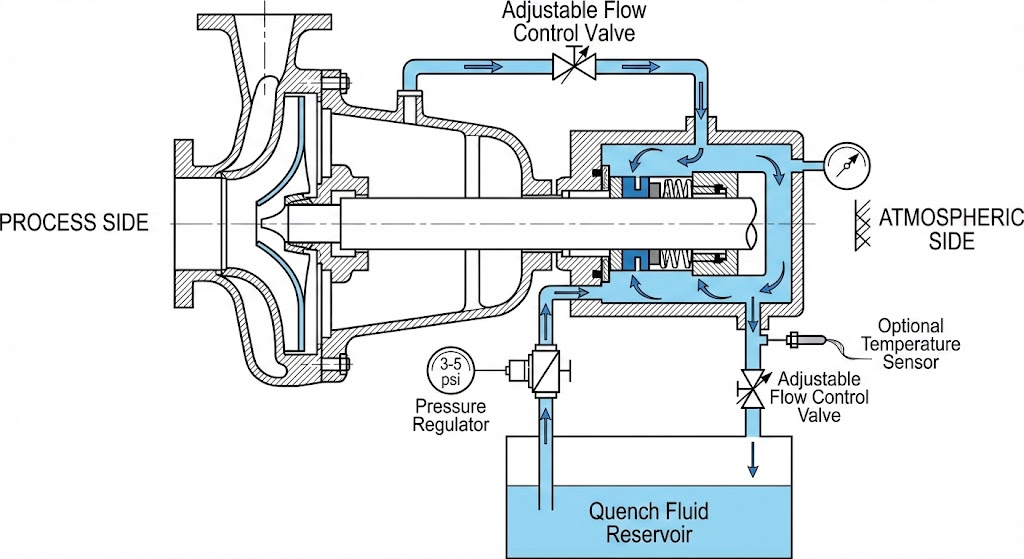

A complete quench system has several key components working together. You’ll need a reservoir that holds your quench fluid. Piping and tubing carry the fluid from the reservoir to the seal and back. Pressure regulators control how hard the fluid hits the seal—too much pressure damages the seal faces, too little and you get inadequate cooling and cleaning. Flow control valves on both inlet and outlet sides let you fine-tune the flow rate. Pressure gauges and flow meters give you visibility into what the system is doing. Many systems also include a heat exchanger to remove excess heat from the quench fluid, keeping temperatures in the safe range.

The type of quench fluid you use depends entirely on your process conditions. Steam quench works for high-temperature applications because it’s dry (superheated), cools effectively, and won’t contaminate your bearing oil. Water quench is simple and inexpensive but requires careful oil condition monitoring to catch water that might sneak into your bearing housing. Nitrogen quench works well for freezing conditions (below 0 degrees Celsius) where water or steam would ice up the seal, and it’s ideal when you need a non-reactive, non-corrosive barrier.

The industry has standardized several piping plans under API 682 (the American Petroleum Institute standard for mechanical seal systems). These standardized plans ensure consistency and allow seal manufacturers to design compatible equipment. API Plan 51 uses a clean, non-pressurized fluid like steam condensate or nitrogen vented to a safe location—simple and low-cost. API Plan 62 uses a clean, pressurized gas from an external source like a plant nitrogen supply. API Plan 65A uses a clean, pressurized liquid like glycol for applications that can’t use steam or gas. Each plan has specific pressure, flow, and temperature requirements designed into it.

Pre-Installation Planning and Preparation

Installation starts long before you touch a wrench. First, evaluate your pumping process carefully. What’s the process fluid temperature and pressure? Is the fluid hazardous, toxic, or flammable? Does it tend to form deposits or solids? What’s the ambient temperature around the pump? These answers determine whether you need quench at all and what type makes sense.

Next, assess what you have available at your plant. Do you have reliable steam supply? Pressurized nitrogen? Clean water? If you’re planning a steam quench, does your steam line deliver dry, superheated steam or wet, saturated steam? (Saturated steam is a disaster—it’ll damage your seal and contaminate your bearing oil.) Understanding your available utilities shapes what’s actually possible.

Select a quench fluid compatible with both your process and your seal materials. Some fluids corrode certain elastomers or coatings, so compatibility matters. If you’re using a heat exchanger, ensure the cooling medium works with your quench fluid. Also consider what happens if the quench fluid mixes with your process fluid—in some cases it’s no problem, in others it ruins the product.

Get the manufacturer’s installation manual and have it handy. Every seal design has specific clearances, gland depths, and tolerances that matter. Also reference API 682 standards. These aren’t just recommendations—they’re proven designs that have worked in thousands of installations. They tell you what pressure limits to respect, what materials to use, and what piping sizes work best.

Gather your tools and materials before you start. You’ll need wrenches, a torque wrench for critical fasteners, clean cloth and rubbing alcohol for cleaning seal faces, the seal components themselves, tubing or piping of the correct material and wall thickness, pressure regulators, flow control valves, gauge isolators, and manifolds. Have spare parts on hand—a broken pressure gauge shouldn’t shut down your installation.

Step-by-Step Installation Procedure

Step 1: Prepare the Seal Chamber

Start by isolating the seal chamber from all flush and quench connection systems. You don’t want pressurized quench fluid accidentally entering the wrong lines or the main pump chamber during installation. Install plastic plugs in all flush/quench connections up to where you’ll actually connect your piping. This keeps dirt and debris out of lines that are disconnected.

Clean the shaft area and seal chamber thoroughly. Use a solvent compatible with your process fluid. Remove any debris, corrosion, or machining dust. De-burr any sharp edges on the shaft and chamber surfaces—those burrs can scratch seal faces or get lodged between components, causing leaks. Visually inspect the chamber to ensure it’s clean enough to eat off of. This step seems tedious, but contamination during installation is one of the top causes of premature seal failure.

Step 2: Set Up Piping and Connections

Design your piping layout carefully. The quench inlet should be on top of the gland and the outlet/drain should be on the bottom. This ensures proper circulation—gravity helps, and you avoid air pockets that can starve the seal of quench fluid. All piping should be sized to minimize pressure drops. Use tubing materials compatible with your quench fluid and process conditions. API 682 specifies minimum wall thicknesses for 1/2 inch to 1 inch outside diameter tubing, and those recommendations exist because they’ve learned what works and what fails.

Install tubing carefully to avoid kinks, sharp bends, or mechanical damage. Route tubing away from hot surfaces and moving parts. Support long runs every 3 feet or so to prevent vibration-induced failures. All connections must be made with appropriate fittings—no improvising with garden hose and hose clamps. Use proper ferrule fittings or threaded NPT connections depending on the line. Make them hand-tight, then use a wrench to bring them up to the manufacturer’s specified torque. Over-tightening splits lines, under-tightening creates leaks.

Step 3: Install Pressure and Flow Control Systems

Mount your pressure regulator close to the seal gland. This keeps the pressure set point as close as possible to where it’s being used, giving you better control. For steam quench, set the regulator to approximately 20 to 33 kilopascals (3 to 5 psi). This is just enough pressure to wash solids off the seal faces without damaging them. For other quench types, follow your equipment manufacturer’s specifications, but remember that quench pressure should generally be limited to 0.2 bar (3 psi) or less.

Install flow control valves on both the inlet side (before the seal) and the outlet side (after the seal). The inlet valve lets you throttle flow into the seal chamber. The outlet valve maintains backpressure, which is how you control the pressure in the seal cavity. This dual-valve setup gives you precision control. Many technicians make the mistake of thinking one valve is enough—it’s not.

Install a flow meter if your system uses one. This lets you actually see that flow is happening and at what rate. Blind guessing is how systems fail. Add pressure gauges before and after the seal gland so you can see actual pressures during operation, not just the regulator setting.

Step 4: Seal Face Preparation and Installation

Clean seal faces one final time with a clean, lint-free cloth and rubbing alcohol just before installation. Don’t touch the faces with your bare hands after cleaning—skin oils are invisible but real. Handle seal components by their outer edges only.

Install seal components according to the manufacturer’s specifications. This usually means: install the stationary seal seat in the gland, install the rotating seal on the shaft with the spring and shaft sleeve, mate the components carefully, and torque fasteners to specification. Every step has tolerances and clearances built in. Rushing or improvising causes installation-related leaks.

Verify proper seal face contact and alignment. Modern seals usually come with setting gauges or fixtures. Use these. Your eyes aren’t precise enough for micron-level tolerances. Once installed, do a hand rotation check—spin the shaft by hand and feel for unusual friction or grinding sounds. The spring should push the rotating face firmly against the stationary face with smooth resistance, not grinding.

Step 5: Configure Support Systems and Monitoring

An oil condition monitoring bottle must be installed in the bearing housing when using steam or water quench. This small sight glass lets you check the oil color without opening the bearing. If you see the oil turning milky white or emulsified, water has gotten in, and it’s time to investigate why your quench system is leaking moisture into places it shouldn’t be.

Install temperature sensors if your design includes them, especially for high-temperature services. These give you early warning when something’s wrong with cooling. Set up baseline readings during successful operation so you know what “normal” looks like.

For steam quench systems especially, ensure the steam is being delivered superheated and dry. Wet steam is a serious problem. It causes water to flash into vapor at the seal faces, creating pressure spikes that damage seals. Worse, water vapor gets into your bearing oil.