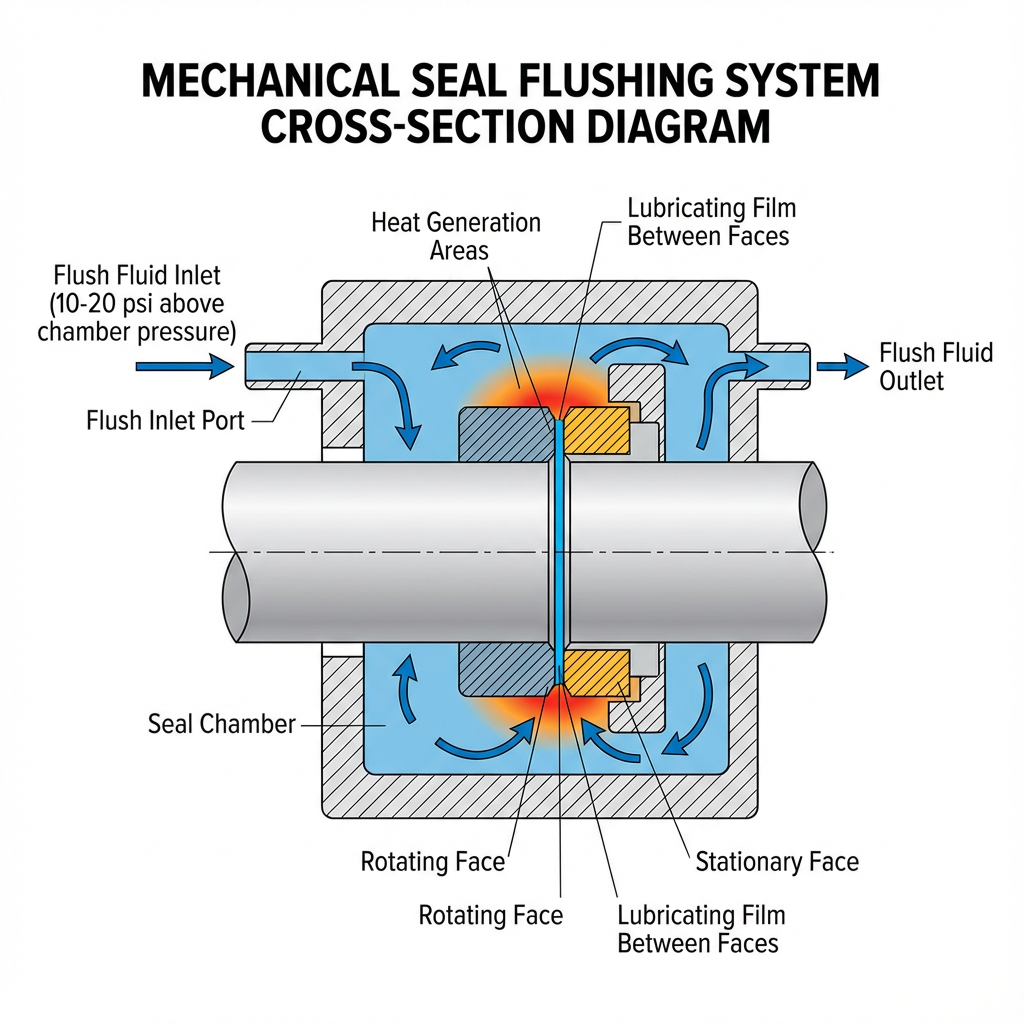

Here’s a number that should grab your attention: 60-70% of all centrifugal pump maintenance work is seal-related. And 99% of those mechanical seal failures? They come from one preventable cause—inadequate lubrication, what engineers call “dry working.”

I’ve seen maintenance teams chase the same pump problems month after month, spending $2,500 or more per repair (and that’s just parts and labor—not counting lost production). The frustrating part? Most of these failures never had to happen.

But here’s the good news: proper flush system maintenance can extend your seal life to 2+ years and deliver ROI within 6-12 months.

What Should You Check During Daily Inspections?

Daily inspections take 5-10 minutes per pump and catch problems before they become failures. Your operators should complete these checks at the start of each shift.

Step 1: Visual Leak Inspection

Walk around each pump and look for signs of leakage. Check the seal housing, all piping connections, and the area beneath the pump.

What you’re looking for:

- Fresh drips or wet spots on the floor

- Fluid stains or residue on the seal housing

- Moisture around pipe fittings and connections

Document any new leakage patterns. A seal that never leaked before but now shows moisture needs investigation—don’t wait for the weekly inspection.

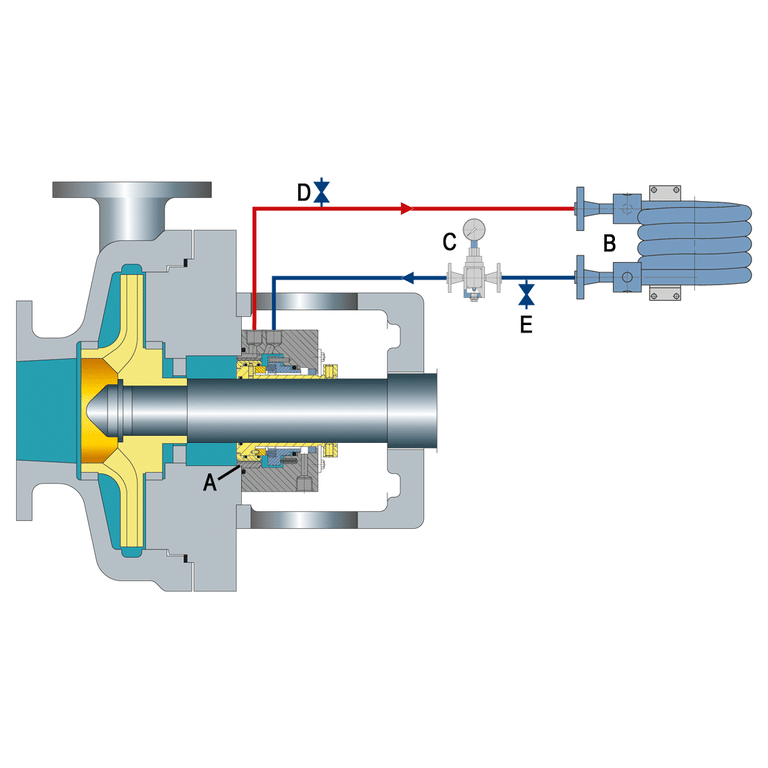

Step 2: Pressure Gauge Readings

Check both the flush pressure gauge and the seal chamber pressure gauge. Write down the readings.

Your flush pressure should read 10-20 psi above the seal chamber pressure. This differential keeps process fluid out of the seal faces. If the gap is too small, contamination risks increase. Too large, and you’re crushing the lubricating film between the faces.

Compare today’s readings to your baseline. A pressure that’s drifting upward or downward by more than 5 psi signals a developing problem.

Step 3: Temperature Monitoring

Check the seal chamber temperature reading. For systems with heat exchangers or coolers, verify you’re getting the expected temperature drop across the unit.

A typical cooler should show a 10-100°F temperature drop, depending on your system design. If the inlet and outlet temperatures are nearly identical, circulation has stopped. That’s an emergency—your seal is running without cooling.

Flag any temperature readings outside your normal operating range for immediate investigation.

Step 4: Audio Inspection

Stand near the pump and listen. Your ears can detect problems that gauges miss.

Warning sounds include:

- Hissing from the seal housing (possible dry running or gas leakage)

- Grinding or scraping noises (seal face contact or bearing issues)

- Puffing sounds (pressure fluctuations in the seal chamber)

Higher-than-normal noise levels often indicate dry running. If you hear grinding, stop the pump immediately—running it further causes irreversible damage.

Step 5: Fluid Level Check (Reservoir Systems)

For Plan 52, Plan 53A, or other reservoir-based systems, check the barrier fluid level through the sight glass.

Document the level and compare it to the previous shift. A dropping level means either an external leak or the seal is consuming fluid. Either situation needs attention before the reservoir runs dry.

What Weekly Maintenance Tasks Keep Your System Running?

Weekly maintenance builds on your daily checks by documenting trends and inspecting components that don’t need daily attention.

Step 1: Document Pressure and Flow Readings

Record all gauge readings in your maintenance log. But don’t just write numbers—compare them.

Pull up last week’s readings. Is pressure gradually increasing? That could indicate filter clogging. Is it decreasing? You might have a developing leak or worn orifice.

Trending toward your limits is a warning sign. A system running at 18 psi differential when your target is 15 psi is telling you something’s changing. Find out what before it becomes a failure.

Step 2: Inspect Physical Components

Give your tubing and piping a thorough visual inspection. You’re checking for:

- Kinks or bends that restrict flow

- Corrosion or discoloration on metal surfaces

- Loose connections or fittings that have worked free

- Damaged mounting brackets or support clamps

Run your hand along accessible tubing. Soft spots, bulges, or unusual warmth indicate problems developing inside.

Verify that all connections are secure. Vibration from pump operation loosens fittings over time. A connection that was tight last month might be finger-loose today.

Step 3: Verify Gauge Calibration Status

Check the calibration certificates for all your instruments. Industry best practice says gauges should be recalibrated every 12 months.

I’ve seen maintenance teams chase “problems” for hours, adjusting valves and checking components, only to discover their pressure gauge was reading 10 psi high. An uncalibrated gauge gives you bad data. Bad data leads to wrong decisions.

If any gauge is past its calibration date, schedule recalibration immediately. Until then, treat its readings with skepticism.

Step 4: Check Filter and Strainer Condition

Filters and strainers protect your seal faces from contamination. When they clog, two bad things happen: flow drops (seal faces overheat) and pressure rises upstream (wasting energy and stressing components).

If your system has sight glasses, inspect the filter element visually. Dark discoloration or visible debris accumulation means it’s time for service.

Check the differential pressure across your filter. Most manufacturers specify a maximum pressure drop—typically 5-15 psi depending on the design. Exceeding this limit means restricted flow and inadequate seal protection.

Schedule cleaning or replacement when differential pressure rises above your threshold.

What Monthly Inspections Prevent Major Failures?

Monthly inspections go deeper than daily and weekly checks. You’re looking at fluid quality, heat exchanger performance, and system configuration—issues that develop slowly but cause expensive failures.

Step 1: Barrier/Buffer Fluid Quality Check

Pull a sample of your barrier or buffer fluid and inspect it carefully. Fluid degradation happens gradually, but the consequences are serious.

Check for these warning signs:

Color changes. Fresh barrier fluid is typically clear or light-colored. Darkening indicates thermal breakdown or contamination from process fluid leaking past the inboard seal.

pH shifts. If your fluid specification includes pH requirements, test the sample. Significant pH changes indicate chemical contamination or additive depletion.

Visible solids or sludge. Hold the sample up to light. Any particles, cloudiness, or settled material means contamination. This debris will damage your seal faces.

Viscosity changes. Fluid that seems thicker or thinner than spec has degraded. Incorrect viscosity means inadequate lubrication.

Here’s a rule worth remembering: never reuse barrier fluid after a seal failure. Failed seals shed debris into the fluid. Even if it looks clean, microscopic particles remain. Installing a new seal with contaminated fluid guarantees a repeat failure.

Step 2: Heat Exchanger Performance Verification

Your heat exchanger keeps seal chamber temperatures safe. When it underperforms, seal life drops dramatically.

Measure the fluid temperature at both the inlet and outlet of your cooler. Calculate the difference.

A healthy heat exchanger shows a clear temperature drop—typically 10-100°F depending on your system design and cooling water temperature. The exact value depends on your specific equipment, but consistency matters more than the absolute number.

If your temperature drop has decreased since last month, the heat exchanger is losing efficiency. Common causes include:

- Scale buildup on tube surfaces

- Fouling from process fluid contamination

- Reduced cooling water flow

No temperature difference at all means circulation has stopped. Check for air locks, closed valves, or blocked passages immediately.

Step 3: Strainer and Filter Service

This is your monthly opportunity for hands-on filter maintenance. Clean or replace strainer elements as needed.

Before and after service, document the differential pressure. This gives you trending data to predict when future service will be needed.

When you remove a strainer element, inspect the captured debris. Normal operation produces fine particles. But if you’re seeing:

- Metal particles – Something upstream is wearing (pump impeller, shaft, or the seal itself)

- Fibrous material – Packing from elsewhere in the system is degrading

- Crystalline deposits – Process fluid is leaking and crystallizing in the flush circuit

These findings tell you what’s happening in your system. Don’t just clean the strainer and move on—investigate the source.

Step 4: Piping and Tubing Inspection

Check that your piping maintains proper slope. API 682 specifies a minimum slope of 0.25 inches per foot (some sources recommend 0.5 inches per foot) upward from the seal to the reservoir.

Why does slope matter? Proper slope allows trapped air to rise back to the reservoir where it can vent. Low spots collect air pockets that block circulation.

Walk the piping route and verify:

- No sagging sections where air can accumulate

- High-point vents are accessible and functional

- No new obstructions pressing against tubing

If you find areas where previous repairs or other work has disturbed your piping slope, correct them now.

Step 5: Valve Position Verification

Confirm that all isolation valves in the flush circuit are fully open. This sounds basic, but mispositioned valves cause a surprising number of seal failures.

Someone troubleshooting a different problem might have partially closed a valve and forgotten to reopen it. Or vibration might have shifted a valve position. Either way, restricted flow means inadequate seal protection.

Check control valves too. Verify they’re delivering the specified flow rate and pressure. Document any valve positions that needed correction—repeated adjustments indicate a valve that needs repair or replacement.

What Quarterly and Annual Maintenance Tasks Are Required?

Quarterly and annual maintenance addresses items that change slowly or require planned downtime. Build these tasks into your preventive maintenance schedule.

Quarterly Maintenance Checklist

| Task | Purpose | Action Required |

|---|---|---|

| Instrument calibration | Ensure accurate readings | Send gauges and transmitters for professional calibration |

| Barrier fluid replacement | Prevent degradation | Drain system completely, flush with clean fluid, refill with fresh barrier fluid |

| Heat exchanger cleaning | Maintain cooling capacity | Chemical clean-in-place (CIP) or mechanical cleaning of tube bundle |

| Documentation review | Identify trends | Analyze three months of maintenance logs for patterns and “bad actor” equipment |

The quarterly fluid replacement deserves special attention. Even if your monthly samples look good, barrier fluids break down over time from heat and contamination. Fresh fluid every quarter prevents gradual degradation from becoming a failure.

When you clean heat exchangers quarterly, you prevent the slow buildup that reduces cooling capacity. A heat exchanger that loses 5% efficiency every month compounds to serious underperformance by quarter’s end.

Annual Maintenance Checklist

| Task | Purpose | Action Required |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive system inspection | Identify hidden wear | Full visual inspection of all accessible components during planned shutdown |

| Seal face condition check | Assess remaining life | Inspect seal faces for wear patterns every 4,000 operating hours |

| Piping system evaluation | Prevent failures | Ultrasonic thickness testing and corrosion assessment of metallic components |

| Support system upgrade review | Improve reliability | Evaluate whether current system meets operational needs; consider upgrades for problem seals |

The annual inspection is your opportunity to look at everything. During planned shutdowns, access components that run continuously. Look for wear, corrosion, and fatigue that daily inspections can’t detect.

If you’re experiencing repeated failures on specific equipment, the annual review is the time to evaluate system upgrades. Converting a problematic single seal with Plan 11 to a dual seal with Plan 53A might solve persistent issues.

How Do You Properly Commission a Seal Flushing System After Maintenance?

After any maintenance that opens or drains the flush system, proper commissioning prevents startup failures. Rushing this process damages seals before they run a single hour.

Step 1: Pre-Startup Inspection

Before adding any fluid, inspect all components for damage or debris. Look inside the reservoir for weld slag, rust, or foreign material from the maintenance work.

Verify all connections are tight. Check especially any fittings that were opened during maintenance.

Confirm valve positions. Isolation valves should be fully open. Control valves should be at their specified positions.

Step 2: System Flush and Fill

Flush the reservoir and piping with clean fluid to remove any contaminants from maintenance. Don’t skip this step—debris from maintenance will damage new seals just as badly as process contamination.

Fill the system with fresh barrier or buffer fluid. Verify you’re using the correct fluid type. Using the wrong fluid—or worse, mixing incompatible fluids—destroys seals and O-rings.

Fill slowly to minimize air entrainment. A partially filled pump creates air pockets that block circulation.

Step 3: Vent the System

Open all high-point vents to remove trapped air. Air in the system stops fluid circulation and allows seal faces to overheat.

For Plan 23 and similar recirculating systems, venting is especially critical. Train your operators to understand that incomplete venting leads to seal damage.

Continue venting until you see steady fluid flow with no bubbles. This might take several minutes. Don’t rush it.

Step 4: Pressurize Gradually

Slowly increase system pressure. Rapid pressurization causes “gas slugging”—sudden pressure spikes that can damage seal components.

Your target pressure is typically 20-50 psi above seal chamber pressure. For Plan 53 systems, API 682 recommends limiting maximum pressure to 150 psig to prevent nitrogen absorption into the barrier fluid.

Increase pressure in stages, pausing to check for leaks at each step.

Step 5: Verify Circulation

Confirm that fluid is actually circulating through the system. The best indicator is temperature differential.

Measure the temperature of fluid leaving the seal chamber and returning from the cooler. The return should be warmer than the supply—heat from the seal faces warms the fluid, and the cooler removes that heat.

If there’s no temperature difference between inlet and outlet, circulation has stopped. Check for air locks, closed valves, or blocked passages before starting the pump.

Step 6: Document Baseline Readings

Record all initial pressure, temperature, and flow readings. These become your baseline for future comparisons.

Note the date, time, and any observations about the commissioning process. If you encountered problems during startup, document what happened and how you resolved it. This information helps troubleshoot future issues.

Key Takeaways for Operations Managers

Mechanical seal flush system maintenance isn’t complicated, but it is critical. The difference between facilities with excellent seal reliability and those fighting constant failures comes down to systematic, documented maintenance.

You have the checklists. You have the procedures. Start with tomorrow’s daily inspection and build from there. Your seals—and your maintenance budget—will thank you.