You should upgrade when your single seal can’t provide adequate protection for your specific application, whether that’s due to regulatory requirements, hazardous fluids, or reliability concerns.

The general rule in the industry is simple: if you can safely and dependably seal it with a single seal, use one. But certain applications demand the extra protection that only a dual seal provides.

How Do You Assess Your Pump’s Upgrade Suitability?

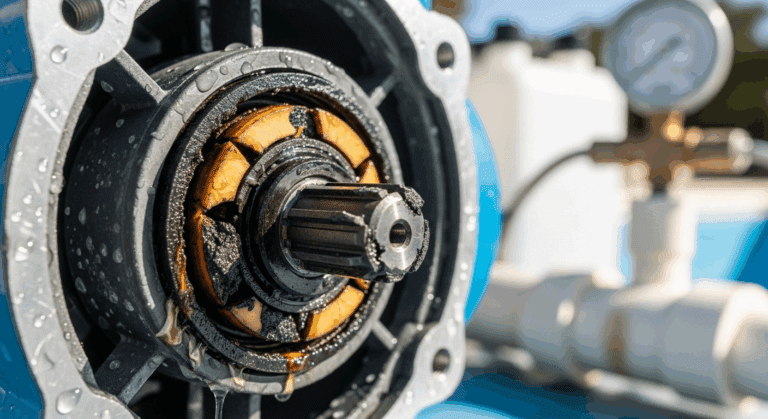

Not every pump can accept a double seal without modifications. Here’s what you need to check before ordering parts.

- Seal chamber dimensions – Your existing stuffing box or seal chamber needs sufficient diameter and length to fit a dual seal assembly. Older pumps may have chambers designed only for packing or small single seals.

- Shaft condition and runout – Measure shaft runout with a dial indicator. You need 0.05mm (0.002 inches) total indicator reading or less for ball and roller bearings. Excessive runout causes vibration that destroys seal faces.

- Piping layout – Dual seals require a barrier or buffer fluid system. Check whether you have space for a reservoir and whether you can route tubing with proper slope for thermosyphon circulation.

- Cartridge vs. component seal – Cartridge seals come pre-assembled and eliminate most installation errors. Component seals cost less but require skilled technicians. If your maintenance team hasn’t installed many dual seals, cartridge is the safer choice.

- Reservoir placement – You’ll need to mount the seal pot at least 18 inches above the shaft centerline. Make sure you have clearance.

What Tools and Materials Do You Need for the Upgrade?

Gather everything before you start. Walking away mid-installation to find a missing tool creates opportunities for contamination and mistakes.

- New double mechanical seal – Cartridge type is strongly recommended. Pre-assembly eliminates measurement errors, protects seal faces during handling, and cuts installation time significantly.

- Barrier or buffer fluid – Must be compatible with your process fluid and seal materials. Avoid fluids with anti-wear or oxidation additives. Never use automotive antifreeze.

- Seal support system components – Reservoir, tubing (minimum 3/4 inch), pressure gauges, level indicators, and heat exchanger if required for your application.

- Dial indicator – For measuring shaft runout. Digital or analog, just make sure it reads in increments small enough to catch 0.002 inch deviations.

- Torque wrench – Gland bolts require specific torque values. Over-tightening distorts the seal; under-tightening causes leaks.

- Clean lint-free cloths and rubbing alcohol – For cleaning seal faces. Any contamination on the faces causes premature failure.

- Manufacturer-recommended lubricant – For O-rings and elastomers. Using the wrong lubricant damages seals before you even start the pump.

- Lockout/tagout equipment – Tags, locks, and whatever your facility requires for energy isolation.

How Do You Prepare the Pump for Seal Upgrade?

Preparation determines whether your new seal lasts three months or three years. Rushing this phase causes most upgrade failures.

Step 1: Implement Safety Lockout/Tagout

Safety comes first. I’ve seen technicians skip this step because “it’s just a quick seal change.” Don’t.

Shut down the pump completely. Disconnect it from the power source at the motor control center, not just the local disconnect. Close both inlet and outlet isolation valves. Depressurize the system by opening drain and vent valves.

If you’re working on a hot service, allow the pump to cool to a safe handling temperature. Some seal elastomers degrade if installed onto a hot shaft.

Tag the equipment as under maintenance and verify that your lockout prevents anyone from accidentally energizing the pump.

Step 2: Remove the Existing Single Seal

Drain any residual process fluid from the seal area. Have containment ready because even “drained” seal chambers hold more liquid than you’d expect.

Remove the coupling guard and coupling. Depending on your pump design, you may need to remove the bearing housing or pull the rotating assembly to access the seal.

Extract the old mechanical seal carefully. Even though you’re replacing it, avoid damaging the shaft or stuffing box surfaces.

Take photos and document the orientation and positioning. This reference helps if questions arise during the new seal installation.

Step 3: Inspect and Clean the Seal Chamber

Clean the seal chamber thoroughly with a solvent appropriate for your process fluid. Remove all traces of the old seal, including gasket material, carbon dust, and deposits.

Inspect the shaft carefully. Look for wear grooves under the old seal location, scoring from debris, pitting from corrosion, and any damage at keyways or shoulders. A worn shaft will destroy your new seal.

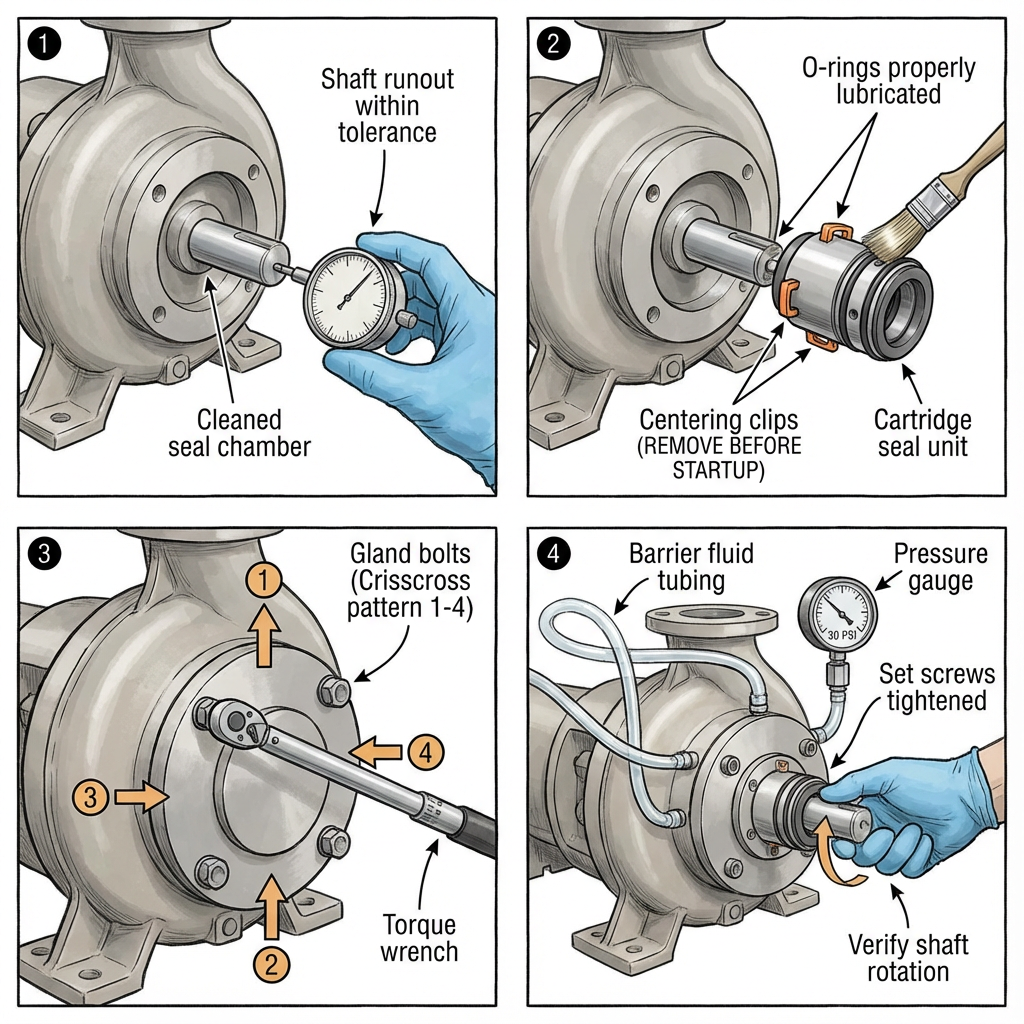

Measure shaft runout with your dial indicator. Position it at the seal mounting location and rotate the shaft slowly. Maximum allowable runout is 0.002 inches total indicator reading for most applications.

Check all gasket surfaces for scratches or pits that could cause leaks.

Run your finger along shaft shoulders, keyways, threads, and any transition where the seal components pass. Sharp edges nick O-rings during installation. Smooth any burrs with fine emery cloth.

If your pump uses a shaft sleeve and it shows wear beyond tolerance, replace it now. Installing a new seal on a worn sleeve wastes the seal.

How Do You Install the Double Mechanical Seal?

This is where cartridge seals really prove their value. Component seals require precise positioning of multiple parts in sequence. Cartridge seals install as a single unit with the faces already properly aligned.

Step 4: Prepare the New Dual Seal Assembly

Keep the seal in its protective packaging until you’re ready to install. Seal manufacturers package components carefully to prevent damage. Every minute the seal sits exposed on a workbench is another opportunity for contamination.

Open the package and verify all components are present. Check for shipping damage, especially on the seal faces. Even a tiny chip or scratch causes leaks.

Clean the seal faces with a lint-free cloth and rubbing alcohol just before installation. Wipe gently in a radial pattern from center to edge.

Never touch the seal faces with bare hands. Oils from your skin leave a film that prevents proper face contact. Wear clean nitrile gloves or handle only the non-sealing surfaces.

Apply a thin film of manufacturer-recommended lubricant to all O-rings and elastomers. This prevents damage when sliding over the shaft. The wrong lubricant, particularly petroleum-based products on certain elastomers, causes swelling and failure.

Step 5: Install the Stationary Seal Components

For component seals, install the stationary seat into the gland or seal housing first.

Make sure the seat is properly aligned and fully seated. Press gently with a soft cloth rather than metal tools. Any scratches on the sealing face cause leaks.

Check that the seat is perpendicular to the shaft axis. Even slight cocking creates uneven face contact and rapid wear.

For cartridge seals, the stationary components are already mounted in the gland assembly. Your main concern is ensuring the gland fits squarely against the stuffing box face.

Step 6: Mount the Rotating Seal Assembly

Slide the rotating assembly onto the shaft with gentle, even pressure. Do not twist. Twisting motion can nick O-rings or misalign spring elements.

Apply steady pressure. If the seal hangs up, stop. Check for burrs you missed or an O-ring that rolled out of its groove.

Make sure the seal face ends up parallel to the stationary face. This is critical. Parallel faces distribute pressure evenly and wear uniformly.

Secure the set screws on clean, undamaged shaft surfaces. Set screws on scored or pitted areas slip when the shaft rotates, causing the seal to spin on the shaft.

For cartridge seals, leave the centering clips or tabs in place. These maintain proper face spacing during installation. You’ll remove them after bolting up the gland.

Step 7: Install the Gland Plate

Position the gland plate against the stuffing box face. The gasket between gland and stuffing box must seat evenly around the entire circumference.

Start all gland bolts by hand before tightening any of them. This prevents cross-threading and ensures the gland can self-align.

Tighten bolts in a crisscross pattern, a quarter turn at a time. This draws the gland down evenly without cocking. Uneven tightening distorts the gland and misaligns the seal faces.

Torque to the manufacturer’s specification. Over-tightening is a common mistake. When a seal leaks, the instinct is to tighten more. But over-torqued glands crush the seal components and make leaks worse.

Verify alignment between rotating and stationary components. The shaft should rotate freely by hand with only slight drag from the seal springs.

How Do You Set Up the Barrier/Buffer Fluid System?

The seal support system keeps your dual seal alive. Without proper barrier fluid circulation, even a perfectly installed seal fails quickly.

Step 8: Install the Seal Support System

Mount the reservoir at least 18 inches above the shaft centerline. This height difference drives thermosyphon circulation when the pump isn’t running. Low-mounted reservoirs don’t circulate fluid during standstill, and seals can overheat on startup.

Use 3/4 inch minimum tubing for all connecting lines. Smaller tubing restricts flow and causes overheating.

Minimize 90-degree elbows. Each sharp turn adds flow resistance. Use large radius bends wherever possible.

Route tubing with continuous upward slope, at least 1/2 inch rise per foot of horizontal run, from the seal gland to the reservoir. Reverse slopes trap air and vapor, blocking circulation.

Install pressure gauges at the reservoir and near the seal gland. Level indicators on the reservoir let you spot fluid loss before it becomes critical.

Step 9: Select and Fill Barrier/Buffer Fluid

Choose a fluid compatible with both your process fluid and your seal materials. If barrier fluid leaks past the primary seal into the process, it becomes part of your product. If it contacts the secondary seal elastomers, it must not cause swelling or degradation.

Avoid fluids with anti-wear or oxidation additives. These additives can form deposits on seal faces. Simple, clean fluids work best.

Never use automotive antifreeze. Ethylene glycol attacks many seal materials and leaves deposits.

Fill the system completely and bleed all air from the lines. Air pockets block circulation and cause localized overheating.

For pressurized systems using Plan 53, charge the reservoir with nitrogen to 20-25 PSI above your maximum seal chamber pressure. This ensures barrier fluid always flows toward the process, never the reverse.

Step 10: Configure Alarms and Monitoring

Install a low-level alarm on the reservoir. Barrier fluid loss indicates a seal problem. You want warning before the reservoir runs dry and the seal fails.

For pressurized systems, add pressure monitoring with low-pressure alarms. Losing pressure means losing the safety margin that keeps process fluid contained.

If you’re using a heat exchanger to cool the barrier fluid, monitor temperature upstream and downstream. Rising delta-T indicates fouling that will eventually cause seal overheating.

Verify all instruments are calibrated and functional before startup. A false sense of security from non-working alarms is worse than no alarms at all.

How Do You Test and Commission the Upgraded Seal?

First startup is when most installation errors reveal themselves. A methodical approach catches problems before they cause damage.

Step 11: Perform Pre-Startup Checks

Remove the cartridge seal centering clips or spacers now. These clips held the seal faces at proper spacing during installation, but they’ll prevent normal operation if left in place. I’ve seen technicians skip this step and wonder why their new seal failed in hours.

Verify pump and motor alignment one more time. Target 0.001 to 0.002 inches. Even slight misalignment from reassembly work causes vibration that destroys seal faces.

Confirm the motor rotation direction matches the pump requirement. Running a pump backward, even briefly, can damage impellers and seals.

Fill the seal chamber with liquid. Never start a pump with a dry seal chamber. Mechanical seals can experience thermal shock and shatter within 30 seconds of dry running.

Start the barrier or buffer fluid circulation system first. The seal needs lubrication before the pump shaft starts turning.

Step 12: Conduct Initial Startup

Rotate the shaft by hand through at least one full revolution. It should turn smoothly with only the resistance of seal springs. Binding or rough spots indicate installation problems that will worsen under power.

Prime the pump if your system requires it. Air-bound pumps cause cavitation and seal damage.

Start the pump and stay at the seal location. Watch and listen for the first several minutes.

Monitor for unusual noises, grinding, squealing, or cavitation sounds all warrant immediate shutdown. Listen for changes in barrier fluid system pressure or level alarms.

Watch for excessive vibration. Some vibration is normal, but increasing amplitude indicates problems developing.

Check for visible leaks at the gland. A few drops during initial startup may be acceptable depending on seal type, but steady flow means something’s wrong.

Feel the gland area for abnormal temperature rise. Overheating indicates inadequate lubrication or face contact problems.

Shut down immediately if you detect any issues. It’s tempting to “let it settle in,” but continuing to run a problem seal causes more damage than stopping to investigate.

Step 13: Monitor Performance During Break-In Period

Record barrier or buffer fluid pressure and level hourly during the first operating shift. These baseline readings tell you what normal looks like for this specific installation.

Check temperature stability in the seal area. Temperature should rise during initial operation and then stabilize. Continuously rising temperature indicates a problem.

Sample the barrier fluid periodically and check for process fluid contamination. Discoloration, odor changes, or chemical test results indicating process fluid mean your primary seal is leaking.

Document everything. Baseline operating parameters become invaluable when troubleshooting future issues. You can’t identify abnormal conditions if you don’t know what normal looks like.