A repaired mechanical seal passes the shop air test, gets reinstalled, and leaks within months. The frustrating part is that the air test acceptance threshold allows leakage up to 7,500 grams per hour, while the original qualification test permits only 5.6 g/hr. That 1,300x gap means a repaired seal can “pass” and still be nowhere near its original performance. I’ve seen this failure pattern dozens of times, and the root cause is almost never the seal itself.

Repaired seals fail again for specific, preventable reasons. Most fall into five categories: uncorrected root causes, compromised face flatness, degraded elastomers, reassembly errors, and inadequate post-repair testing.

Why the Original Failure Comes Back

The single most common reason a repaired seal fails again is that nobody fixed what killed it the first time. Replacing the seal without addressing the system is like changing a tire without fixing the pothole.

I worked on a Goulds 3196 ammonia pump at a temperature-controlled warehousing facility that burned through a seal in under a year after replacement. The seal showed heavy wear, but the real problems were improper piping with tight 90-degree elbows instead of gentle slopes, and severe shaft misalignment. Once we corrected the piping geometry and performed laser alignment, that pump ran flawlessly.

Heinz P. Bloch’s analysis of 11,000 seal failures across 148 plant sites found that 13% were attributable to bearing maintenance failures alone. Bearing distress creates shaft deflection and vibration that no seal repair can overcome. Before reinstalling any repaired seal, verify shaft runout, bearing condition, alignment, and piping configuration. The API 682 standard specifies these checks for a reason.

Seal Face Quality After Repair

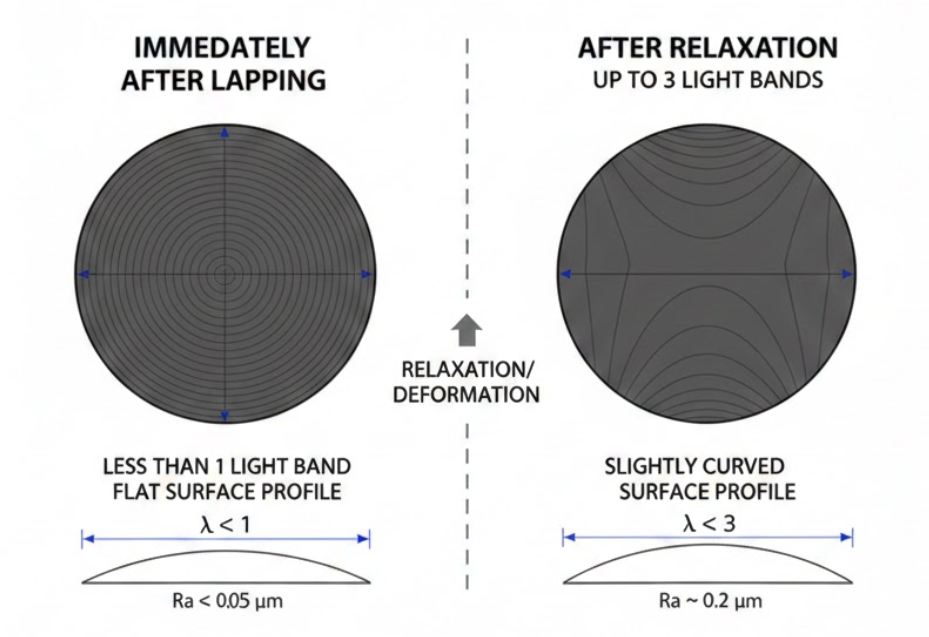

Face flatness is where most repair shops fall short. The tolerances are unforgiving: carbon and glass-filled PTFE faces require 2 to 3 helium light bands, while tungsten carbide, silicon carbide, and ceramic faces need 1 to 2 light bands. For pressures above 40 bar, everything tightens to within one light band. One helium light band equals 0.3 microns.

What the spec sheet doesn’t tell you is that carbon graphite faces relax after lapping. A face lapped to less than one light band can read as high as three light bands after sitting. Technicians who do not know this will either falsely reject a properly lapped face or, worse, accept a genuinely out-of-spec face because “they all read high.” Carbon faces return to flat against a hard mating face during operation, so the post-lapping reading alone is not the final answer.

Available wear on seal faces typically ranges from 1/16 to 3/16 of an inch. Once that material is consumed, adjacent components begin rubbing. During repair, measure remaining wear length. If the face is already near its limit, lapping it flat again just removes more material and shortens the next service interval.

Elastomer Degradation and Reuse Mistakes

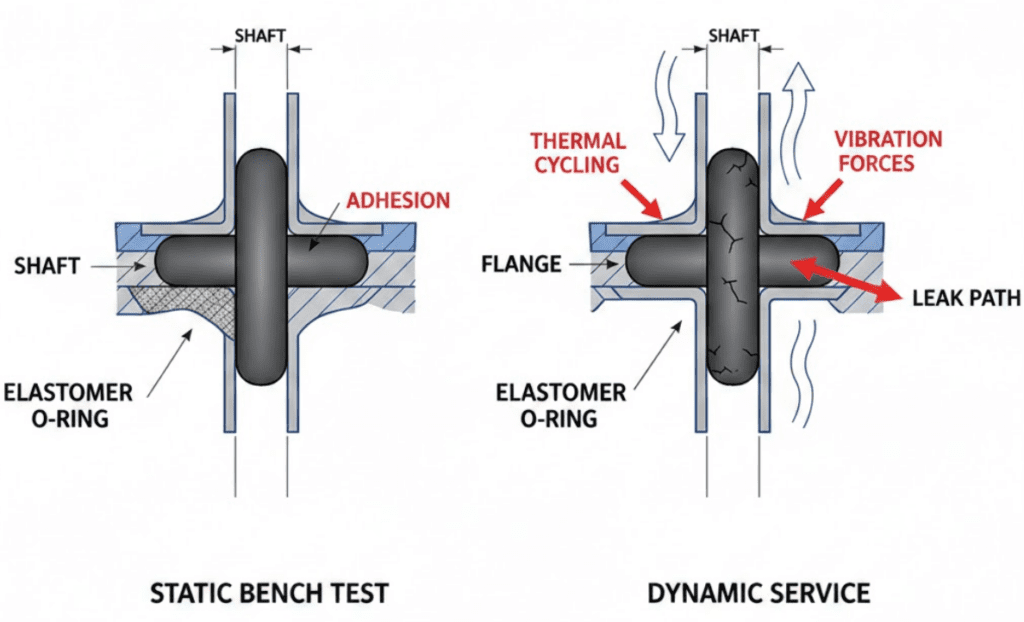

Reusing O-rings on a repaired seal is the most common cost-saving shortcut that backfires. The problem is that degraded elastomers can pass every bench test you throw at them.

O-rings can remain leak-tight under static conditions even when material properties have already degraded badly. Adhesion between the seal and flange surfaces masks the loss of elasticity. On the bench, the O-ring seals. Under dynamic operation with thermal cycling and vibration, it fails.

The end-of-lifetime threshold for O-rings is 80 to 85% compression set. EPDM at 150 degrees Celsius reaches 89% compression set increase in just 70 days, with elongation at break dropping 91% and stress relaxation dropping 86%. Those numbers mean a reused EPDM O-ring from a hot service pump is almost certainly past its functional limit, even if it looks fine.

Wrong lubricant choice during reassembly destroys elastomers just as fast as aging does. Petroleum lubricants cause EPR O-rings to swell within five days. Buna N rubber has only a one-year shelf life due to ozone sensitivity. Never use silicone, PTFE, or petroleum-based lubricants on EPR elastomers. Use only the emulsion lubricant specified by the seal manufacturer.

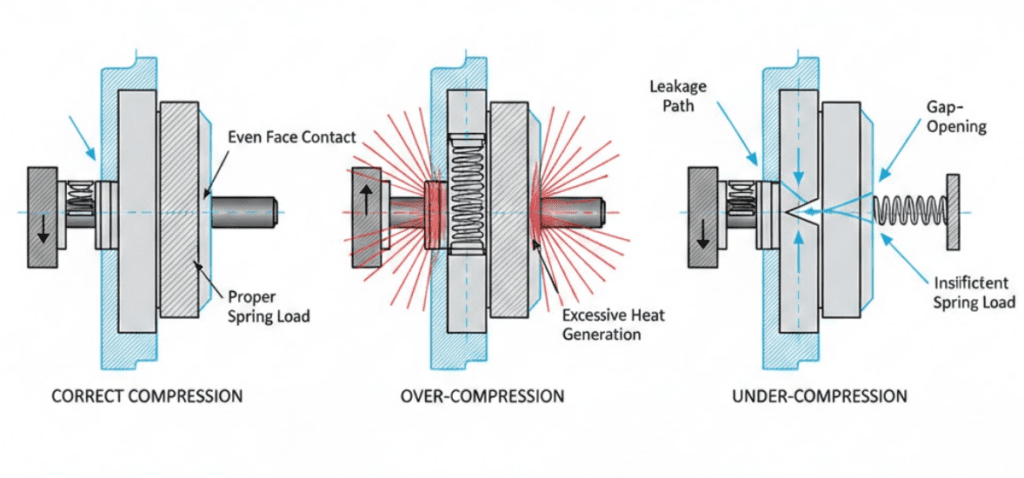

Reassembly and Compression Errors

Wrong compression setting is the most frequent reassembly mistake on repaired seals. Over-compression generates excess heat at the faces and accelerates wear. Under-compression allows the faces to open as the seal wears, and leakage starts within weeks.

Shaft surface condition gets overlooked during repair. Scratches, nicks, and dings running longitudinally under the seal will seep and cause a leak. The shaft surface under the seal needs a mirror finish. If the shaft was machined down during a previous repair, that reduced cross-section weakens structural integrity and changes the seal setting dimension.

Before reinstalling, check three things: lube, square, and clean. Use vinyl gloves when handling seal faces. A single fingerprint deposits enough contamination to score a lapped face during break-in. Verify the gland plate is not cocked, and confirm anti-rotation pins are not oversized. Either condition causes uneven circumferential wear that mimics a face flatness problem but is actually an alignment issue.

For cartridge seals, never push on the gland during installation. That loads the seal from the wrong end and creates over-compression that does not show on any external measurement.

Post-Repair Testing and Inspection

Passing a shop air test does not mean a repaired seal will perform in service. The API 682 air test accepts up to 7,500 g/hr leakage, while qualification tests permit only 5.6 g/hr. A repaired seal that barely passes the air test has a 1,300x margin of error compared to its original qualification.

IECEx regulations require that a repaired seal perform exactly as stated in the documentation for the original seal, including seal face temperature rise data and misalignment capability. Full traceability of replacement parts is mandatory. API 682 Edition 4 specifies clearance tolerances of 1 mm for seals up to 60 mm and 2 mm for seals larger than 60 mm.

After repair, perform a complete seal inspection before reinstallation. Check face flatness with an optical flat, verify elastomer compression set, confirm dimensional tolerances against the OEM drawing, and examine wear patterns on the removed seal. Good-looking faces with documented leakage point to secondary seal element failure rather than face wear, meaning the O-rings failed while the faces were still serviceable.

When to Stop Repairing

A simple repair typically runs 10 to 20% of a new seal’s price, making it attractive for expensive custom-engineered seals. But standard cartridge seals follow a different calculus.

Replace when repair costs exceed 50% of a new seal’s price. Material fatigue accumulates with each repair cycle and never fully resolves. A seal repaired twice that fails a third time should be replaced outright. The pattern at that point indicates a fundamental mismatch between the seal and the application, or accumulated degradation that repairs cannot reverse.

For custom or high-value seals where replacement lead times are long, repair makes sense if the root cause has been identified and corrected. For standard cartridge seals with short lead times, the third failure is the decision point. Cowseal offers both replacement seals and custom seal solutions for applications where repeated repair failures indicate a need for reengineering rather than another rebuild.

Preventing Repeat Failures

The most common failure I see with repaired seals is not a repair quality problem. It is a diagnostic problem. The seal gets rebuilt to spec, passes the air test, gets reinstalled into the same conditions that caused the original failure, and fails again on schedule.

Before any repaired seal goes back into service, answer one question: what killed it last time? If you cannot answer that with specifics, the repair is a temporary fix regardless of how well it was executed. Verify the system, not just the seal.