Mechanical seals fail approximately 85% of the time rather than wearing out. That distinction matters because a seal that fails gives you warning signs — if you know where to look. I’ve spent years watching plants invest in vibration monitoring while ignoring the single parameter that reveals the actual root cause: seal chamber pressure.

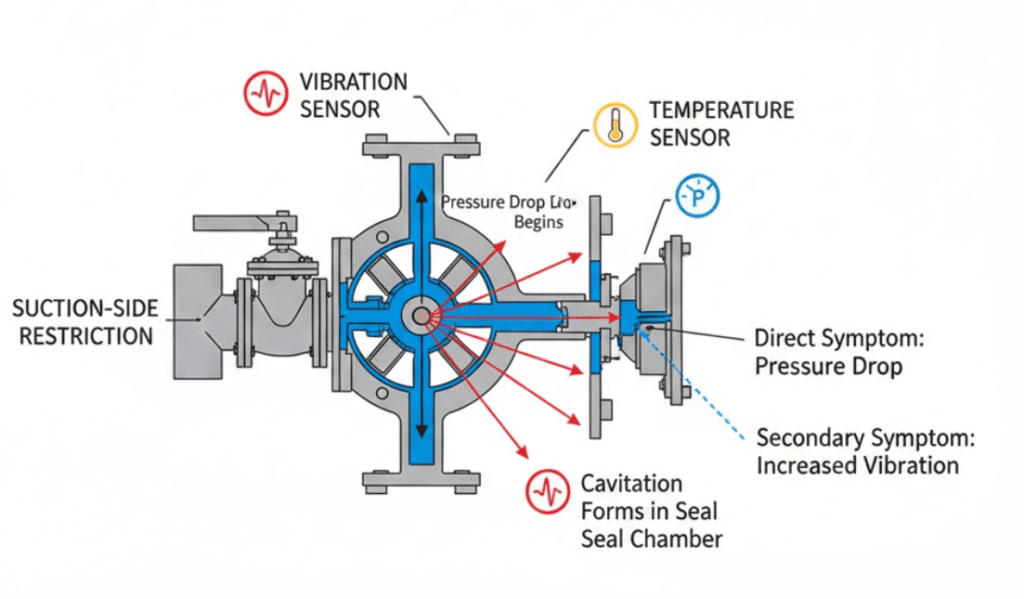

About 80% of these failures trace back to process effects on pump flow rate. Vibration picks up the symptoms. Pressure data tells you why the seal is degrading and how much time you have before it needs to come out.

Why Pressure Monitoring Catches What Vibration Misses

Pressure changes in the suction and discharge sides of a pump directly disturb seal chamber conditions. A rise in vibration followed by increased seal chamber temperature and a pressure drop usually points to a suction-side restriction. If you only monitor bearing vibration and surface temperature, those process-driven changes go completely undetected.

I’ve seen this failure pattern dozens of times: a plant chases vibration readings for weeks, replaces the seal, and watches the new one fail in the same timeframe. The vibration was a secondary symptom. The primary cause — a pressure condition that starved the seal film — never got addressed.

The mechanical seal acts as a fuse in the pump system. It fails because of an overload or process upset elsewhere. Pressure monitoring lets you diagnose whether the fuse is being stressed before it blows, giving you weeks of lead time instead of an emergency shutdown. Temperature monitoring adds value as a confirming parameter, but pressure changes typically appear first because they reflect the process condition directly rather than through heat buildup delay.

Establishing Pressure Baselines

Generic pressure thresholds are starting points, not answers. Every pump has its own normal operating envelope, and you need to establish that baseline before pressure data becomes meaningful.

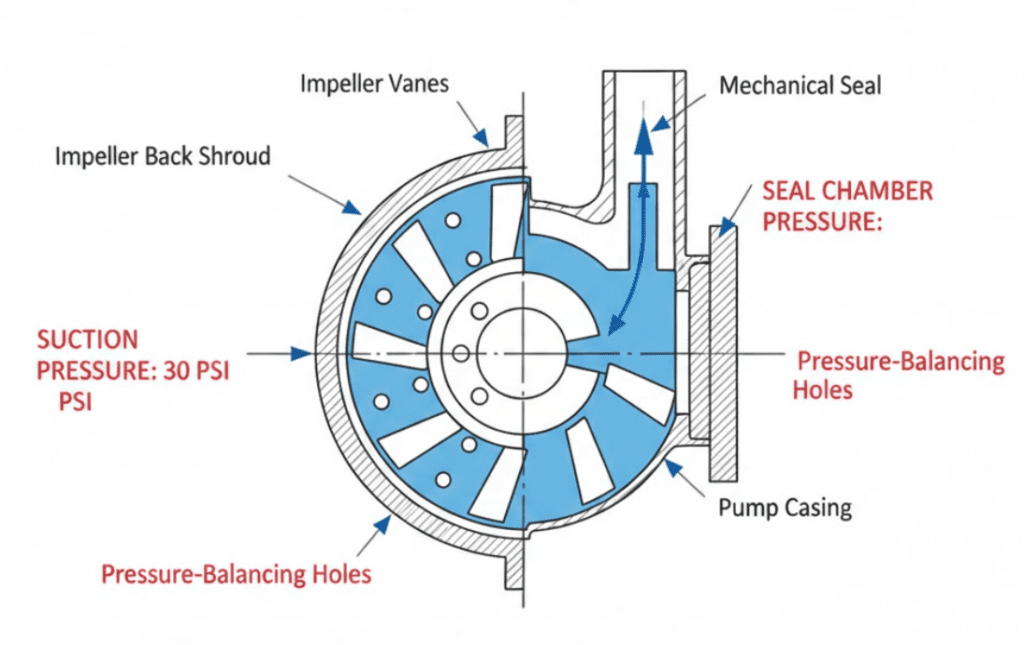

The seal chamber pressure calculation starts with one key relationship: chamber pressure tracks near suction pressure, not discharge pressure. Pressure-balancing holes drilled through the impeller ensure this. A good baseline rule of thumb is flush pressure set 25 psi above suction pressure. For the seal chamber itself, maintain a minimum of 25 psi above the fluid’s vapor pressure to prevent flashing across the seal faces.

To establish your baseline:

- Record suction pressure, discharge pressure, and seal chamber pressure simultaneously during stable, on-design operation.

- Repeat at three to five operating points across the pump’s flow range.

- Log flush flow rate — approximately 3 to 4 GPM per inch of shaft diameter for older seal designs, less for modern cartridge seals.

- Document ambient temperature and process fluid temperature at each point.

This creates your pump-specific reference. Any deviation analysis is only as good as the baseline it compares against. I recommend retaking baselines after any pump maintenance, impeller change, or process fluid modification.

One critical mistake I see: plants setting flush pressure based on discharge pressure rather than suction pressure. One facility set flush pressure at 100 psi based on discharge pressure when suction pressure only required 20 psi. That over-pressurization accelerates face wear and wastes resources.

Pressure Deviation Thresholds and Failure Patterns

Once baselines are established, a 10% pressure deviation from the healthy baseline should trigger a predictive alert. Use these zones as starting guidelines:

| Zone | Deviation from Baseline | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | Within 10% | Continue monitoring |

| Caution | 10-25% deviation | Increase monitoring frequency, investigate root cause |

| Alarm | >25% deviation or sudden shift | Schedule repair, prepare replacement seal |

| Emergency | Pressure collapse or rapid uncontrolled change | Shut down and inspect immediately |

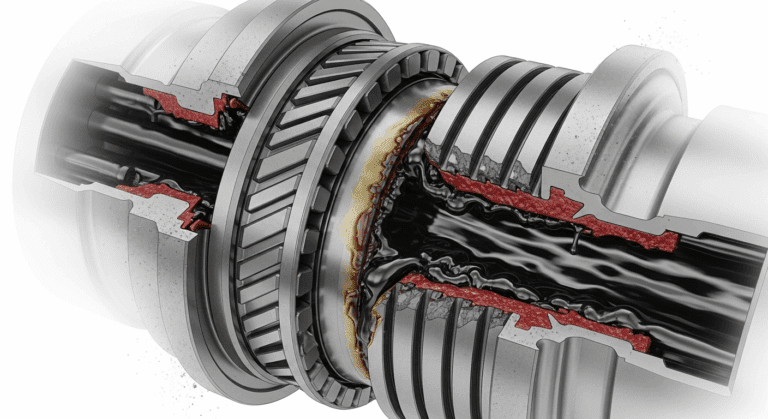

The real value of pressure monitoring is correlating pressure patterns with specific failure modes. Gradual pressure increase with stable temperature typically indicates face wear narrowing the seal gap — the chamber backs up against increasing resistance. A sudden pressure drop accompanied by temperature rise points to dry running from loss of lubrication film.

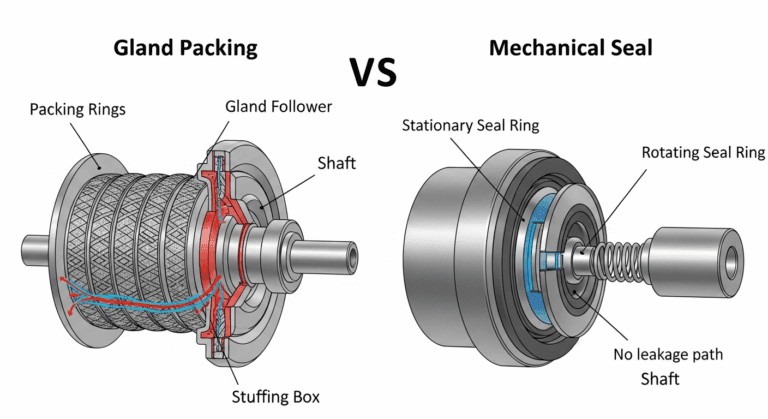

Narrow wear tracks on seal faces indicate the seal operated under excessive pressure, deforming the face. Wide, uneven wear marks suggest misalignment rather than a pressure problem. Grooves across the face point to vibration-induced separation allowing particles between the faces.

When flush plan pressure drifts below the required margin, product migrates between the seal faces. I worked on a case where an automotive e-coat pump kept fracturing stationary seat rings on restart. The flush pressure was not high enough to keep the tacky product out. Adhesion built up during shutdown, and restart torque cracked the seat. Setting flush fluid pressure 15 psi above maximum seal chamber pressure eliminated the problem.

Response Protocols and Dual Seal Considerations

Knowing when to act is as critical as detecting the deviation. Before replacing a seal, check whether the pressure anomaly stems from a process change, a plugged flush line, or a support system issue. A common false alarm is pressure fluctuation during pump startup or flow changes — compare against your multi-point baseline rather than reacting to a single reading.

For single seals, the decision path is straightforward: investigate the root cause at caution level, plan a maintenance window at alarm level, and shut down at emergency level. Pressure that is too high or too low both cause damage, but through different mechanisms — excessive pressure accelerates face wear while insufficient pressure allows process fluid ingression and dry running.

Dual seal monitoring adds complexity. For Plan 53A barrier systems, maintain barrier fluid pressure a minimum of 20 to 25 psig above maximum process pressure. For Plan 52 unpressurized buffer systems, buffer pressure must remain below 40 psig. A rising buffer pressure in a Plan 52 system indicates inner seal leakage — the process side is pressurizing the buffer cavity. That is an early warning that the inner seal needs attention within days to weeks, not months.

The API 682 4th edition made a significant change: transmitters are now the default instrumentation, replacing pressure switches. A switch gives you an on/off signal. It cannot indicate how far you are from an alarm setpoint, so it cannot predict problems. Transmitters enable continuous trending — the difference between knowing you have a problem and knowing one is developing.

For organizations still using switches, I recommend upgrading critical pumps to transmitters first. The investment pays for itself with the first avoided unplanned shutdown. I worked on a 65% nitric acid transfer pump that was burning through seals every five weeks. We installed continuous pressure monitoring and within days spotted negative seal chamber pressure — a valve was positioned wrong, starving the seal of lubrication. Correcting that one valve projected seal life from 1.2 months to over 24 months.

Getting Started

Start with your highest-failure-rate pumps. Install transmitters, establish baselines at stable operating points, and set initial alarm thresholds at the zones outlined above. Refine those thresholds as you accumulate trend data specific to each pump.

The biggest mistake is treating pressure monitoring as a checkbox rather than a diagnostic system. A number on a gauge means nothing without context — baseline, trend direction, rate of change, and correlation with process conditions. Get those elements in place, and you will catch seal failures weeks before they become emergency shutdowns.