A single mechanical seal failure costs about $2,500 in repair labor alone. That’s before you count lost production, which can run into tens of thousands. And here’s what most facilities don’t realize: flush system problems are behind a huge chunk of these failures.

I’ve seen technicians replace seal after seal on the same pump, never realizing the real culprit was a plugged orifice or wrong pressure setting. Once you understand what causes flush problems, you’ll spot them before they destroy your seals.

The most common flush problems fall into four categories: pressure issues, flow rate problems, contamination, and temperature failures. Each one leaves specific warning signs. This guide will teach you to recognize those signs and fix the root causes—not just swap parts.

What Are the Warning Signs of Mechanical Seal Flush Problems?

Your seals tell you when something’s wrong with the flush system. You just need to know what to look for.

Visual Indicators You Can Spot During Rounds

Black carbon dust accumulating on the outside of a seal is one of the clearest warning signs. This dust means the seal faces aren’t getting enough lubrication, or the liquid film between them is vaporizing. Either way, the flush system isn’t doing its job.

Other visual red flags include:

- Visible leakage or dripping around the seal gland

- Product buildup or crystallization near the seal faces

- Discoloration of seal components (often indicates heat damage)

- Wet spots or staining on floors beneath the pump

Sounds and Operational Symptoms

A squealing sound during operation almost always points to inadequate lubrication. The seal faces are running dry or nearly dry.

Watch for these operational symptoms:

- Squealing or grinding noises from the seal area

- Unusual vibration that wasn’t there before

- Temperature gauge readings climbing above normal

- Pressure fluctuations on your flush system gauges

Any sudden change from normal baseline readings deserves immediate attention.

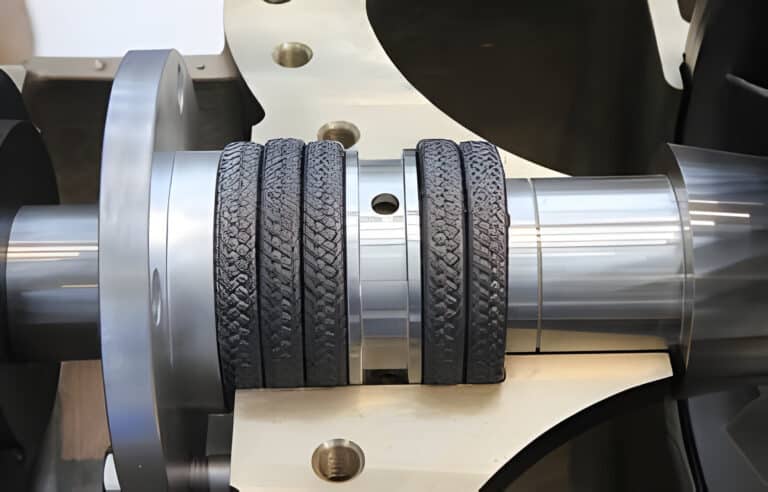

What Do Wear Patterns on Failed Seals Tell You?

When you pull a failed seal, the wear pattern tells the story. Grooves or notches cut into the seal face point to abrasive contamination or excessive pressure crushing the lubricating film.

Heat checking—those tiny cracks that look like dried mud—comes from thermal stress. The seal got too hot. This usually means the flush system failed to remove enough heat.

Scoring patterns across the face indicate contamination getting between the seal faces. The flush fluid brought in particles that shouldn’t have been there.

Even wear across the entire face? That’s actually normal wear at end of life. Uneven wear, on the other hand, suggests alignment problems or vibration issues.

Why Is My Seal Flush Pressure Wrong?

Wrong flush pressure is one of the fastest ways to kill a mechanical seal. Too low, and process fluid contaminates your seal. Too high, and you crush the lubricating film between the faces.

What Should Normal Flush Pressure Be?

The right pressure depends on your flush plan and application:

| Flush Plan | Required Pressure |

|---|---|

| Standard (Plan 11) | 10-15 psi above seal chamber pressure |

| API Plan 32 | Minimum 15 psi (1 bar) above stuffing box pressure |

| API Plan 53A | Minimum 1.5 bar above seal chamber pressure |

| Vapor margin | Minimum 50 psi above fluid vapor pressure (per API 682) |

These aren’t suggestions. They’re the minimum requirements for reliable seal operation.

What Causes Low Flush Pressure?

When pressure drops below spec, start looking for these common causes:

- Clogged orifice or filter—by far the most common culprit

- Leaks in piping, fittings, or connections

- Undersized supply lines restricting flow

- Regulator malfunction or incorrect setting

- Insufficient source pressure (your supply can’t deliver what you need)

A flow meter can help you spot problems quickly. Higher-than-normal flow with lower pressure often means a face seal leak. Lower flow with higher pressure points to a filter clog.

What Causes High Flush Pressure?

High pressure causes just as much damage as low pressure. The seal faces get pushed together too hard, destroying the lubricating film.

Look for:

- Misadjusted or stuck regulator

- Blocked return lines preventing fluid from leaving the seal chamber

- Closed or partially closed valves

- Incorrect orifice sizing (too small restricts flow)

When pressure keeps climbing past expected values, the regulator is probably misset or stuck.

How Do I Diagnose Pressure Problems Step by Step?

Here’s a systematic approach that works:

Step 1: Verify gauge accuracy first. I’ve seen technicians spend hours troubleshooting a problem that didn’t exist—all because of an uncalibrated gauge. Compare your reading against a known-good gauge before doing anything else.

Step 2: Check pressure at source and at seal. Measure both points. A big drop between them tells you the problem is in your piping run.

Step 3: Inspect regulator settings and function. Is it set correctly? Does it respond when you adjust it? A stuck regulator won’t regulate anything.

Step 4: Look for leaks, blockages, and restrictions. Walk the line. Check every connection. Look for wet spots, crimped tubing, or plugged components.

Step 5: Compare readings to design specifications. Pull the seal vendor’s data sheet. The assumed seal chamber pressure should be listed there. If your measured value doesn’t match, you’ve found your problem.

Why Is My Seal Flush Flow Rate Inadequate?

Flow rate problems are sneaky. You might have perfect pressure readings, but if flow is wrong, your seal still fails.

How Much Flow Does My Seal Actually Need?

Required flow varies by seal type and shaft size:

| Seal Type | Flow Rate Requirement |

|---|---|

| General minimum | 0.25-0.50 gpm |

| Component seals (running) | 3-4 gpm per inch of shaft diameter |

| Cartridge seals | Approximately 1/3 of component seal requirements |

| Idle/standby | Approximately half of running flow rate |

Modern cartridge seals need much less flow than older component seals. That’s one reason they’re more reliable. But even cartridge seals need some flow.

What Happens When Flow Is Too Low?

Insufficient flow creates a cascade of problems. The flush can’t remove heat fast enough, so temperatures climb. Contaminants build up on the seal faces because nothing’s washing them away. The lubricating film between faces gets too thin.

The seal faces experience increased contact pressure. Abrasion accelerates. In extreme cases, you end up with dry running conditions—and that can destroy a seal in under 30 seconds.

What Happens When Flow Is Too High?

Too much flow causes erosion of the seal faces and other components. High-velocity fluid literally wears away the seal surfaces.

You’re also wasting flush fluid and driving up operating costs. Seals without proper flow controls can consume 20-30 gallons per minute. That adds up fast.

How Do I Check and Correct Flow Problems?

Step 1: Measure actual flow rate at seal inlet. Don’t guess. Use a flow meter or calibrated container and stopwatch.

Step 2: Check for orifice blockage using the temperature drop test. With a Plan 11 system, measure temperature across the orifice. If the temperature drop exceeds 10%, the orifice is plugging up. Clean it immediately.

Step 3: Inspect filters, strainers, and cyclone separators. Clogged components restrict flow. Check condition and clean or replace as needed.

Step 4: Verify pipe sizing matches requirements. API 682 specifies minimum 12mm (0.5″) tubing for shafts 60mm and smaller, and 18mm (0.75″) for larger shafts.

Step 5: Confirm valve positions are correct. It sounds obvious, but I’ve seen seal failures caused by nothing more than a valve left partially closed.

What Causes Seal Flush Contamination Problems?

Contamination turns your flush system into an abrasive delivery system. Instead of protecting the seal, it destroys it.

What Are Common Sources of Flush Contamination?

The contamination can come from almost anywhere:

- Mineral buildup from plant water (calcium, silica, iron)

- Corrosion particles from aging piping

- Process fluid migrating into the flush system

- Debris from pump wear (impeller, volute, wear rings)

- Bacterial growth in closed-loop barrier fluid systems

Plant water is a frequent offender. End users should verify their seal water meets industry standards for impurity size, silicate content, organic impurities, iron content, and water hardness.

How Does Contamination Damage Seals?

Abrasive particles score the seal faces. Those ultra-flat, ultra-smooth surfaces that keep your seal working? Contamination scratches them up. Once the faces are damaged, leakage increases.

Deposits clog orifices and filters, reducing flow. Chemical contamination attacks elastomers—your O-rings swell, harden, or crack. Solids accumulate on the faces and accelerate wear.

Why Are My Seal Temperatures Running High?

Heat kills seals. Every component has temperature limits, and exceeding them accelerates degradation.

What Temperature Limits Should I Watch?

API 682 recommends limiting seal chamber temperature rise to less than 10°F. That’s not much room for error.

The vapor pressure margin matters too. Your seal chamber pressure should stay at least 50 psi above the fluid’s vapor pressure at operating temperature. Drop below that margin, and the fluid starts flashing to vapor between the seal faces. That vapor provides zero lubrication.

Check your seal vendor’s specifications for material-specific limits. Different elastomers and face materials have different tolerances.

What Causes Overheating in Flush Systems?

High temperatures usually trace back to one of these causes:

- Inadequate flush flow rate (not enough cooling capacity)

- Heat exchanger malfunction or fouling

- Cooling water supply problems (flow, temperature, or availability)

- Wrong flush plan for the application

- High-viscosity fluids generating excess friction heat

The seal faces generate heat just by rubbing together. Under normal conditions, the flush carries that heat away. When cooling fails, heat accumulates.

How Do I Troubleshoot Temperature Problems?

Step 1: Measure temperature at flush inlet and outlet. This tells you how much heat the flush is removing.

Step 2: Check heat exchanger performance. Compare the temperature drop across the cooler to design specifications. Fouling reduces heat transfer.

Step 3: Verify cooling water flow and temperature. Is the plant water system delivering adequate flow at the right temperature?

Step 4: Confirm flush flow rate meets requirements. Low flow means low cooling capacity.

Step 5: Review if current flush plan suits the application. Sometimes the original plan selection was wrong for the service conditions. High-temperature applications might need Plan 21 (which adds a cooler) instead of basic Plan 11.

What Are Common Flush System Piping Defects?

Bad piping defeats everything else you do right. The best seal and the perfect flush plan won’t help if the piping prevents proper flow.

What Are the Correct Piping Installation Standards?

API 682 spells out the requirements:

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Material | 300 series stainless steel (EN 1.4401) |

| Minimum tubing size (shaft ≤60mm) | 12mm (0.5″) |

| Minimum tubing size (shaft >60mm) | 18mm (0.75″) |

| Slope | Minimum 10mm per 240mm, continuous upward to reservoir |

| Orifice bore | Minimum 3mm (0.125″) |

| Reservoir volume (shaft ≤60mm) | Minimum 12 liters (3 gallons) |

That slope requirement is critical. All lines must slope continuously upward from the seal gland to the reservoir. A half-inch per foot (40mm per meter) is recommended.

What Piping Mistakes Cause Flush Failures?

I see the same mistakes over and over:

- Wrong slope direction—piping should slope upward to the reservoir, not downward

- Tight 90-degree elbows instead of gentle gradual bends

- Undersized tubing that creates flow restrictions

- Air pockets from improper venting (especially on vertical pumps)

- Crimped, kinked, or damaged tubing

Air in the system is particularly problematic. The inclusion of air at startup can lead to issues with the seal support system. Vent the piping loop before starting, especially on vertical pumps.

How Do I Inspect and Correct Piping Issues?

Walk the entire line from seal to reservoir:

- Check slope continuously—no dips, no flat spots, no reverse slopes

- Look for kinks, tight bends, or crushed sections

- Verify all connections are tight and leak-free

- Confirm vents are installed at high points and functional

- Check that tubing size matches specifications throughout

Any restriction in the line reduces flow. A single tight elbow can cut flow enough to cause problems.

How Do I Troubleshoot Specific API Flush Plans?

Different flush plans fail in different ways. Knowing what to look for speeds up your troubleshooting.

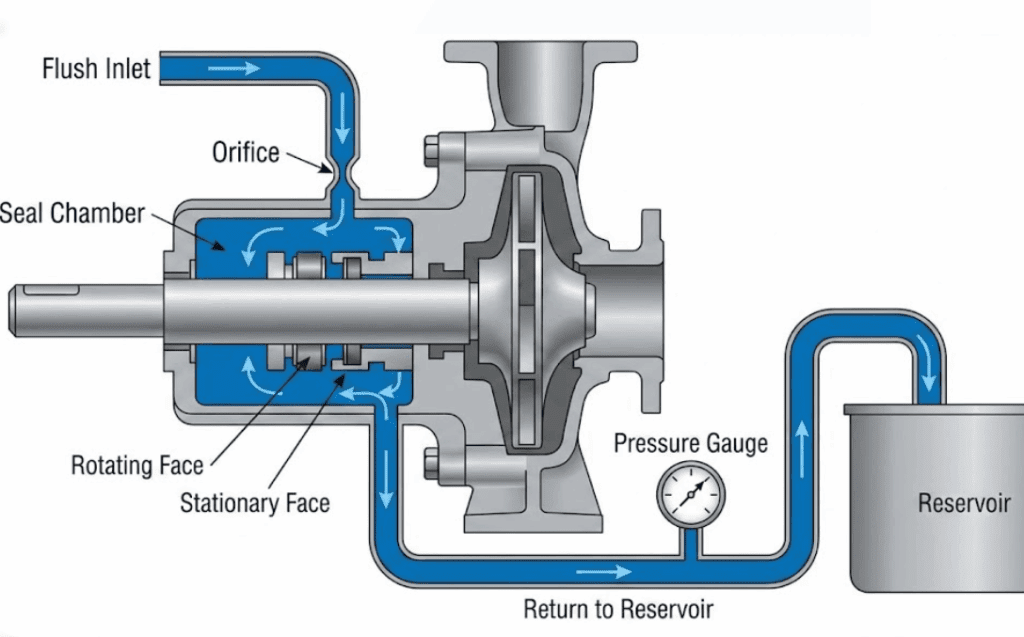

API Plan 11: What Goes Wrong with Internal Recirculation?

Plan 11 is the most common arrangement. It takes fluid from pump discharge through an orifice and sends it to the seal chamber. Simple, but not foolproof.

Common Plan 11 problems:

- Orifice plugging—check the temperature drop across the orifice; more than 10% drop means it’s clogging

- Inadequate differential pressure (not enough difference between discharge and seal chamber)

- Dirty process fluid contaminating the seal

- Confusion about drain vs. flush connections (they’re not the same thing)

One common question: where does the flush liquid go after entering the seal? It passes through the seal and returns to the pump through the throat bushing. The drain connection is for the atmosphere side, not the process side.

API Plan 32: What Goes Wrong with External Flush?

Plan 32 uses an external clean fluid source. It’s great for dirty processes, but it has its own failure modes:

- Insufficient supply pressure (needs to be at least 15 psi above stuffing box pressure)

- Operators restricting flow during standby to minimize consumption—this causes startup failures

- Mineral buildup in flow control valves from plant water

- Temperature not controlled adequately

That standby problem deserves special attention. Some operators restrict flow to pumps on hot standby to save water and prevent cooling. This leads to contamination and corrosion. When the pump starts up, the seal fails almost immediately.

API Plan 52/53: What Goes Wrong with Dual Seal Systems?

Dual seal systems with buffer or barrier fluid are more complex:

- Barrier fluid degradation or contamination over time

- Incorrect pressurization—Plan 53 requires maintaining pressure above the seal chamber

- Nitrogen supply pressure drop (the accumulator or supply runs low)

- System leaks allowing process fluid to contaminate the barrier

- Failure to replace fluid after seal failure

Never reuse barrier fluid after a seal failure. The contamination from the failure stays in the fluid and damages the replacement seal. Clean the entire system—reservoir and all tubing—before refilling.

Wrapping Up

Most mechanical seal flush problems come down to four things: pressure, flow, contamination, or temperature. Get those right, and your seals last years instead of months.

Start with the basics. Check your gauges daily. Walk your piping runs. Look for the warning signs before they become failures. When a seal does fail, take the time to find out why.

Your seals are trying to tell you something. Now you know how to listen.