You’re standing at the pump, watching fluid drip from the seal area, and your production line just came to a halt. A leaking double mechanical seal costs you more than just the price of a replacement seal. The real hit comes from downtime, lost production, and the scramble to figure out what went wrong.

Here’s what most technicians don’t realize: about 69% of pump failures trace back to sealing problems. But the seal itself isn’t always the culprit. In my experience working with field service teams, roughly 80% of what we call “seal failures” turn out to be problems with the support system, operating conditions, or installation issues.

How Do You Identify Where the Leak Is Coming From?

Finding the leak source quickly saves you hours of unnecessary work. The first step is understanding that double seals have three distinct leak paths, and each one tells a different story.

What Are the Three Possible Leak Paths in a Double Seal?

- Inboard seal leaking into the barrier cavity: Process fluid crosses the primary seal and contaminates your barrier or buffer fluid. You won’t see external leakage immediately, but your reservoir level will rise and the fluid will change color or smell.

- Outboard seal leaking to atmosphere: This is the visible leak you can see dripping from the gland area. Barrier fluid escapes to the environment, and your reservoir level drops.

- Support system components leaking: Tubing connections, fittings, reservoir seams, or valve packing can all leak barrier fluid without any seal face damage.

How Do You Distinguish Between Process Fluid and Barrier Fluid Leakage?

Start with a simple two-question test:

- Is fluid escaping externally from the seal area?

- Has the barrier fluid reservoir level dropped?

If fluid is escaping but your reservoir level stays constant, you’re losing process fluid through both seal sets. That’s a serious situation requiring immediate shutdown.

If your reservoir level is dropping but you see no external leak, check all your tubing connections and fittings first. The system might be leaking somewhere upstream of the seal.

Visual identification helps too. Barrier fluids like glycol solutions or synthetic oils look different from most process fluids. Check the color, consistency, and smell of what’s leaking. Compare it to a fresh sample of your barrier fluid.

Trending your reservoir level over time gives you the clearest picture. A gradual decline over weeks indicates normal seal face wear. A sudden drop points to a system leak or catastrophic seal failure.

What Should You Check First When a Double Seal Starts Leaking?

Check your support system before you blame the seal. I’ve seen technicians pull perfectly good seals because they didn’t verify the basics first. The barrier or buffer system is your first line of defense, and it’s also the most common source of problems.

Step 1: Verify the Barrier/Buffer Fluid System

Check reservoir fluid level against your baseline. Every system should have a marked normal operating range. If you don’t have baseline marks, establish them now for future reference.

Verify system pressure. For pressurized barrier systems (API Plan 53), you need 1.5-2 bar (22-29 psi) above stuffing box pressure. For unpressurized buffer systems (API Plan 52), pressure should stay near atmospheric. A pressure reading outside these ranges tells you something’s wrong before you even touch the seal.

Inspect for visible leaks. Follow every tubing run from the reservoir to the seal and back. Check compression fittings, threaded connections, and valve stems. A small drip at a fitting can look like a seal leak.

Confirm proper venting. Trapped air causes circulation problems that starve seal faces of lubrication. On Plan 52 systems, verify the reservoir vent is open. On pressurized systems, make sure you’ve purged all air during the last refill.

Check thermosyphon flow. If your system relies on natural circulation, feel the tubing. The line leaving the seal should feel warmer than the return line. No temperature difference means no flow.

Step 2: Inspect External Components

Examine gland plate bolts. Uneven torque distorts the seal face and causes leakage. Check that all bolts are present and tightened in the correct sequence. The manufacturer’s spec usually calls for a crisscross pattern.

Look at static seals. O-rings and gaskets between the gland and stuffing box can fail independently of the mechanical seal. Look for extrusion, hardening, or visible gaps.

Check tubing condition. Kinked, pinched, or collapsed tubing restricts flow. Make sure nothing has shifted since installation.

Verify valve positions. Someone may have closed an isolation valve during maintenance and forgotten to reopen it. Check every valve in the support system.

Inspect heat exchangers. Blocked coolers cause overheating. If your system has a cooling loop, verify flow through the heat exchanger.

Step 3: Assess Operating Conditions

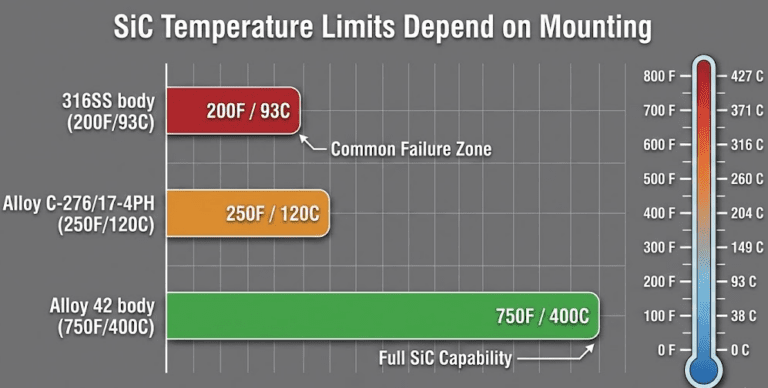

Compare current temperature to normal. A seal running 20°F hotter than usual has a problem. Either cooling is inadequate or friction has increased due to dry running or contamination.

Verify pressure against design specs. High seal chamber pressure accelerates wear. Low pressure can cause vaporization at the seal faces.

Check pump operating point. Running far from Best Efficiency Point (BEP) causes shaft deflection that hammers the seal. Ask operations if anything changed recently.

Note recent process changes. Different fluid properties, temperature swings, or pressure spikes all stress seals. A process change often precedes a seal failure by days or weeks.

How Do You Read Seal Face Wear Patterns?

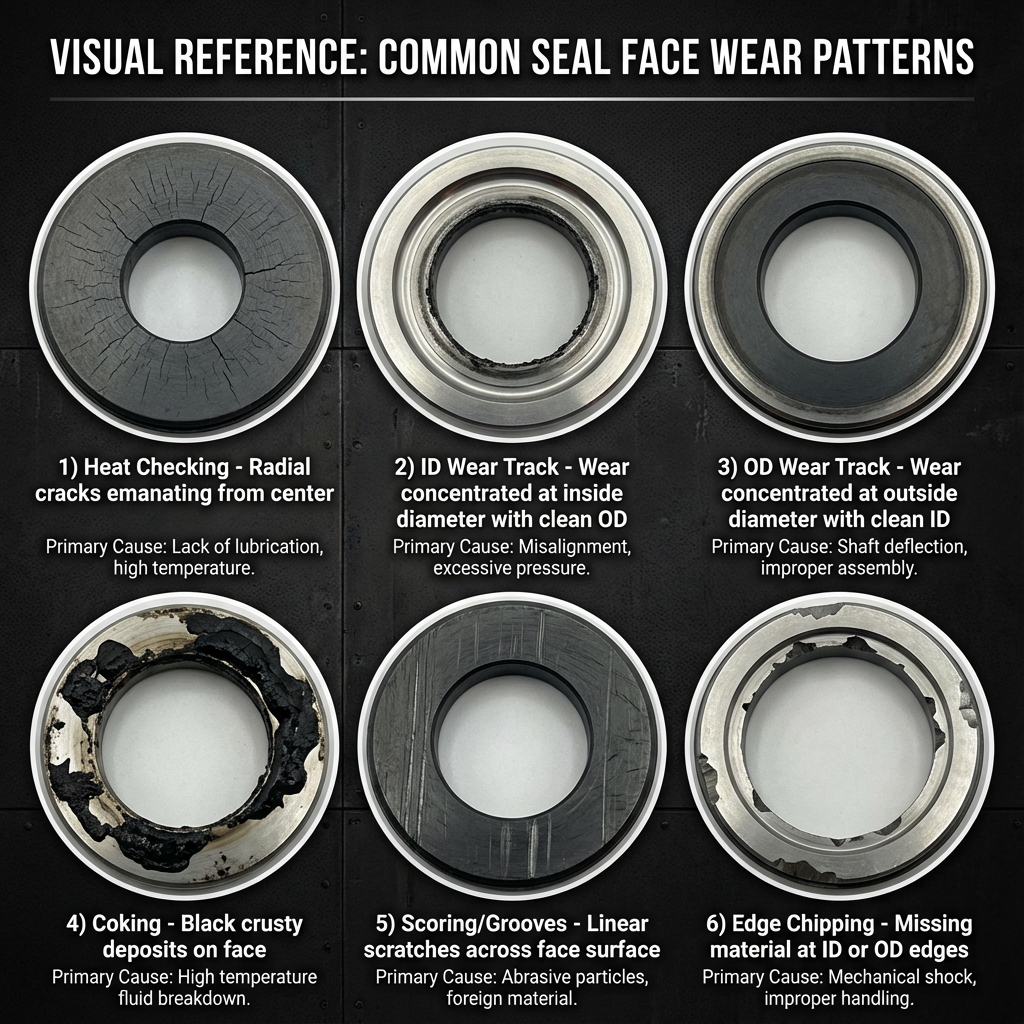

Seal faces tell a story. The patterns left behind reveal what conditions the seal experienced before failure.

| Wear Pattern | What It Looks Like | Likely Cause | What to Fix |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat checking | Radial cracks spreading from the center | Inadequate lubrication, insufficient cooling, vaporization at faces | Improve flush flow, check for dry running conditions |

| ID wear track | Wear concentrated at inside diameter only | Thermal distortion (faces running too hot) | Increase cooling capacity, reduce operating temperature |

| OD wear track | Wear concentrated at outside diameter only | Pressure-induced coning (negative rotation) | Verify pressure is within design limits |

| Coking | Black crusty deposits on atmospheric side | High temperature oxidation of leaked fluid | Improve cooling, switch to cleaner flush source |

| Scoring | Deep scratches running across the face | Abrasive particles trapped between faces | Improve filtration, verify flush fluid cleanliness |

| Chipping | Material missing from face edges | Pressure spikes, thermal shock, rough handling | Review startup procedures, check for cavitation |

The wear track width matters too. A narrow, centered track indicates good alignment and proper loading. A wide or off-center track points to face distortion or misalignment.

I find it helpful to compare the wear pattern on both the rotating and stationary faces. They should mirror each other. Mismatched patterns suggest something shifted during operation.

How Do You Troubleshoot Barrier/Buffer Fluid System Issues?

The support system deserves its own diagnostic process. Plan 52 (buffer) and Plan 53 (barrier) systems work differently, so they fail differently too.

What Should You Check on API Plan 52 (Buffer) Systems?

Plan 52 systems circulate unpressurized buffer fluid between the seal faces using natural thermosyphon action. The buffer provides lubrication and carries heat away from the seal.

Step 1: Verify the reservoir vent is open. Plan 52 operates at atmospheric pressure. A blocked vent pressurizes the system and changes how the seal works.

Step 2: Check buffer fluid level and condition. The level should be within the marked operating range. Pull a sample and check color, clarity, and odor. Darkening or a chemical smell indicates overheating or contamination.

Step 3: Confirm thermosyphon circulation. Touch the tubing. The line from the seal back to the reservoir should feel warmer than the supply line. Equal temperatures mean no circulation.

Step 4: Inspect level indicators and gauges. Stuck float switches or inaccurate gauges give you bad information. Verify readings manually.

Step 5: Look for process contamination. If your buffer fluid smells like the process fluid or has changed color dramatically, the inboard seal is leaking. This is normal wear over time, but rapid contamination indicates a problem.

What Should You Check on API Plan 53A/B/C (Barrier) Systems?

Plan 53 systems maintain barrier fluid at higher pressure than the seal chamber, forcing any leakage toward the process rather than the atmosphere. These systems require more monitoring.

Step 1: Verify nitrogen supply. Check supply pressure at the regulator and confirm gas is flowing. A depleted nitrogen bottle is an easy problem to miss.

Step 2: Check accumulator pre-charge (Plan 53B/C). Bladder and piston accumulators need correct pre-charge pressure to function. Low pre-charge reduces system response.

Step 3: Confirm barrier pressure. You need 1.5-2 bar (22-29 psi) above seal chamber pressure. Lower pressure compromises the seal. Higher pressure wastes barrier fluid and stresses the inboard seal.

Step 4: Monitor pressure decay rate. After pressurizing, watch how fast pressure drops. Rapid decay indicates a leak somewhere in the system. Slow decay is normal as barrier fluid migrates across the seal faces.

Step 5: Check refill frequency trends. API 682 suggests sizing accumulators for 28-day hold-up time. If you’re refilling more often than that, something is consuming barrier fluid faster than expected. Increasing refill frequency over time warns you that seal condition is deteriorating.

What Are Critical Monitoring Parameters?

| Parameter | Normal Range | When to Take Action |

|---|---|---|

| Barrier pressure | 1.5-2 bar above stuffing box | Pressure drop exceeds 0.5 bar |

| Temperature rise | Less than 15°F (water-based) or 30°F (oil-based) | Exceeding these limits |

| Fluid level | Within marked operating range | Level drop requiring refill more than weekly |

| Fluid condition | Clear, consistent color | Any discoloration, particles, or odor change |

The temperature rise limit is based on API 682 guidelines. Water-based fluids transfer heat better, so they’re allowed less temperature rise before indicating a problem. Oil-based barrier fluids tolerate more temperature differential.

Trending matters more than single readings. A gradual pressure decline over months is different from a sudden drop overnight. Both indicate problems, but different ones.

What Steps Should You Follow for Systematic Diagnosis?

Random troubleshooting wastes time. A systematic workflow gets you to the root cause faster and reduces the chance of missing something.

Complete Diagnostic Workflow

Step 1: Stop and assess. Before touching anything, identify where the leak is coming from and what type of fluid you’re seeing. Is it process fluid or barrier fluid? Is it coming from the seal or the support system?

Step 2: Check the support system first. This step catches 80% of problems. Verify pressure, level, temperature, and flow before assuming the seal faces failed.

Step 3: Review operating parameters. Compare current conditions to design specs. Temperature, pressure, and flow rate should all fall within the seal’s rated envelope.

Step 4: Inspect external components. Look at everything you can see without disassembly. Bolts, tubing, fittings, valves, and static seals all fail independently of the mechanical seal.

Step 5: Preserve evidence if seal removal is required. Follow the preservation steps outlined earlier. A clean seal tells you nothing.

Step 6: Examine seal faces for wear patterns. Match what you see to the pattern guide. The pattern reveals operating conditions.

Step 7: Check shaft and housing conditions. Measure shaft runout and surface finish. Look for corrosion, fretting, or scoring under the seal components.

Step 8: Investigate upstream causes. Bearing condition, pump alignment, and vibration levels all affect seal life. A new seal installed in a misaligned pump will fail the same way.

Step 9: Document everything. Your notes help during future troubleshooting and provide data for reliability trending.

Quick Reference: Symptom-to-Cause Matrix

| Symptom | Most Likely Causes | Check First |

|---|---|---|

| Sudden external leak | Outboard seal failure, static seal failure | Gland bolts, O-rings, barrier pressure |

| Gradual barrier level drop | Normal inboard seal wear, system leak | Pressure trend, connection integrity |

| Rapid barrier fluid darkening | High temperature, contamination | Cooler function, circulation flow |

| Excessive heat at seal | Dry running, insufficient flush | Barrier level, circulation, flush flow |

| Vibration increase | Bearing wear, misalignment, cavitation | Bearing condition, alignment check |

This matrix gets you started, but don’t stop at the first match. Multiple factors often combine to cause failures.

Making It Stick

Troubleshooting a leaking double mechanical seal doesn’t have to be frustrating. A systematic approach gets you to the root cause faster and prevents the same failure from happening again.

Start with the support system. Most “seal failures” aren’t really seal failures at all. They’re system problems that damaged an otherwise good seal.

When you do find a failed seal, read what it’s telling you. Wear patterns reveal operating conditions. Preserving the seal for professional analysis pays dividends when you’re dealing with repeat failures.

Document everything. Your notes today become your troubleshooting guide tomorrow. Trending refill frequency, temperature, and pressure over time gives you early warning before the next leak starts.

If you’re seeing the same failure repeatedly despite fixing the obvious causes, it’s time to involve the manufacturer’s technical support. Some problems require engineering analysis that goes beyond field troubleshooting.

The seal manufacturers have seen thousands of failures. Use their experience to solve your toughest problems. The investment in proper diagnosis and prevention pays back quickly in reduced downtime and lower maintenance costs.