Why is your mechanical seal leaking just hours after you installed it?

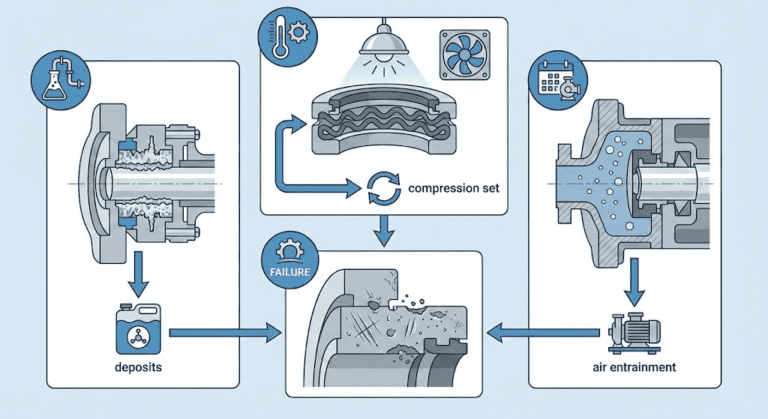

I’ve seen this pattern dozens of times: a technician follows the installation procedure, torques everything to spec, starts the pump, and watches the seal weep. The instinct is to blame the seal or tighten the gland. Both responses are usually wrong. More than two-thirds of seal failures trace back to equipment issues, not seal defects.

In my experience, most post-installation leaks can be diagnosed without removing the seal. The key is a systematic static-to-dynamic test sequence that isolates the failure location before you reach for a wrench.

Start with a Static Pressure Test

Before you start the pump, pressurize the seal chamber and watch what happens. Static testing reveals secondary seal problems that dynamic testing masks.

The API 682 standard specifies this for a reason. The integrity test allows a maximum pressure drop of 2 psi over 5 minutes from a reservoir pressurized to 25 psig. If you exceed this threshold, you have an assembly error or manufacturing defect in the secondary seals, not a face seal problem.

For a more rigorous check, the standard also defines a 20 psi static hold at room temperature for 4 hours. I recommend this extended test for any seal going into critical service.

What the spec sheet doesn’t tell you: if leakage is small during static pressure, the problem is almost always the O-rings or gaskets. Large static leakage points to the primary seal faces. This distinction determines your next diagnostic step.

If the static test passes, you’ve confirmed the secondary seals are intact. Any leak that appears during operation must come from the seal faces, which narrows your investigation.

Verify Equipment Tolerances Before Blaming the Seal

When a properly assembled seal leaks immediately after startup, the pump is usually the problem. Before replacing the seal, check these six parameters:

Shaft runout: Maximum 0.002 inches (0.05 mm) TIR at any point along the shaft. One deepwell pump installation leaked within hours, and the root cause was the shaft not passing squarely through the seal chamber. If the shaft isn’t centered, the seal flexes with every rotation, opening the faces cyclically.

Seal chamber face runout: API 610 specifies 0.0005 inches per inch of seal chamber bore diameter, TIR. A 4-inch bore should have no more than 0.002 inches of face runout. Exceeding this causes uneven loading on the seal faces.

Shaft endplay: Maximum 0.010 inches (0.25 mm) TIR regardless of bearing type. Excessive endplay allows the rotary seal face to lift off the stationary face during thrust reversals.

Radial shaft movement: Ball or roller bearings should allow only 0.002 to 0.004 inches of radial play. More than this indicates worn bearings that will destroy any seal you install.

Shaft-to-bore concentricity: 0.001 inches per inch of seal chamber bore diameter. Misalignment here causes the same cyclic flexing as shaft runout.

Seal compression: Verify the working length matches the manufacturer’s specification, typically within 0.030 inches. Over-compression distorts the faces; under-compression allows separation.

I’ve seen countless seals replaced when the real problem was worn pump components. Measure first.

What the First 30 Seconds of Startup Reveal

If static testing and tolerance verification pass, the startup itself becomes your diagnostic tool.

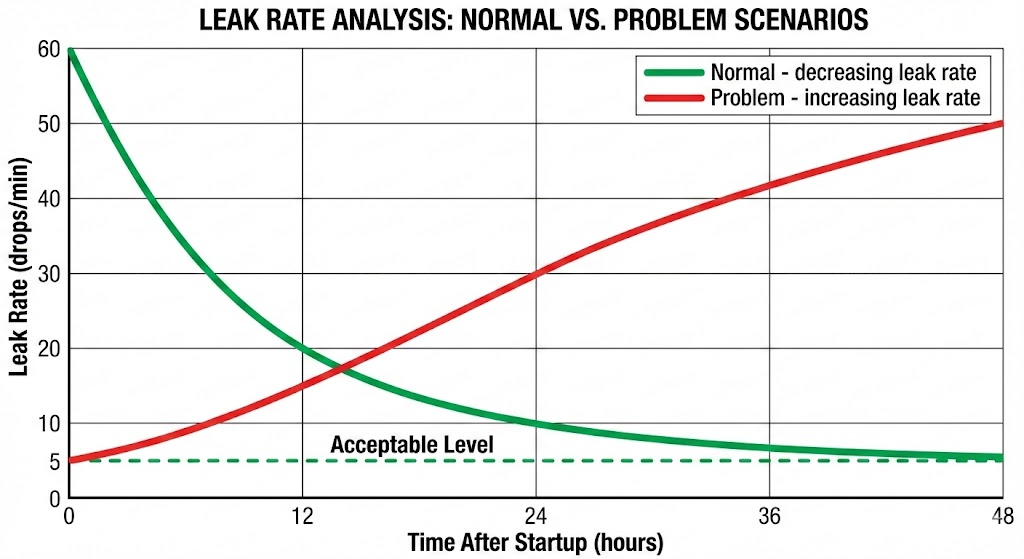

A new seal should leak slightly during initial operation. The faces need to bed in, which means the leakage rate should trend downward over the first few hours. If a seal starts to leak and the leakage trends upward, impending failure is likely.

Watch the seal during the first 30 seconds. Immediate heavy leakage at startup, when static testing showed no leak, indicates the faces cannot maintain contact under dynamic conditions. This points to shaft runout, misalignment, or vibration issues that the static tolerances didn’t catch.

Acceptable leakage for most applications is 10 drops per hour or less. Split seals typically run 10 to 15 drops per minute initially, decreasing to 2 to 7 drops per minute after 24 hours of operation. If your seal exceeds these benchmarks and the rate is increasing rather than decreasing, the faces are failing to form a proper film.

The first startup also reveals thermal issues. If the seal runs fine for several minutes, then begins leaking as it heats up, you have a thermal distortion problem. Check your flush plan flow rate and temperature.

When to Remove the Seal

Not every leak can be diagnosed in place. About 20% of post-installation failures require seal removal for definitive root cause analysis.

Remove the seal when:

- Static and dynamic tests are inconclusive

- Leak rate is increasing and tolerance checks pass

- You suspect internal seal damage from installation

- Face pattern analysis is needed to identify the failure mode

At a cold storage facility, a Goulds 3196 ammonia pump seal failed in less than one year. The customer assumed the seal was defective. Complete disassembly revealed the root cause was not the seal, but worn pump components, improper piping with tight 90-degree elbows, and significant shaft misalignment. The systematic diagnosis saved them from repeating the same failure with a replacement seal.

Face wear patterns tell the story after removal: full contact indicates proper installation; ID-only contact suggests thermal distortion; OD-only contact points to pressure distortion; wide contact bands mean misalignment. But you need to get there systematically, after exhausting in-place diagnostics.

Diagnostic Sequence Summary

Before you pull the gland:

- Static pressure test: 25 psig, allow 2 psi drop maximum in 5 minutes. Fail means secondary seal issue.

- Tolerance verification: Shaft runout under 0.002 inches, face runout under 0.0005 inches per inch bore, endplay under 0.010 inches.

- Startup observation: Leakage should trend down, not up. Watch the first 30 seconds for immediate face separation.

- Remove only if: In-place tests are inconclusive or leak rate increases despite passing tolerance checks.

This sequence catches the majority of post-installation problems before you spend hours on an unnecessary seal change. The most common failure I see: engineers replace the seal when the real problem is the equipment parameters. Measure everything the shaft runout measurement procedure specifies before ordering a new seal.

When proper mechanical seal installation doesn’t prevent immediate leakage, the answer is almost never “bad seal.” It’s almost always “bad conditions.” Find the conditions, and you solve the problem permanently.