Mechanical seal failures cost industrial operations millions in downtime and repairs every year. The culprit? Seal water pressure imbalances that most maintenance teams overlook until it’s too late.

Seal water keeps your mechanical seals alive by cooling, lubricating, and flushing away contaminants. When the pressure is wrong—whether too high or too low—the consequences cascade quickly. A pressure spike lasting just hours can crack seal faces. Pressure drops allow contamination that ruins seals in days.

How Does Seal Water Pressure Work?

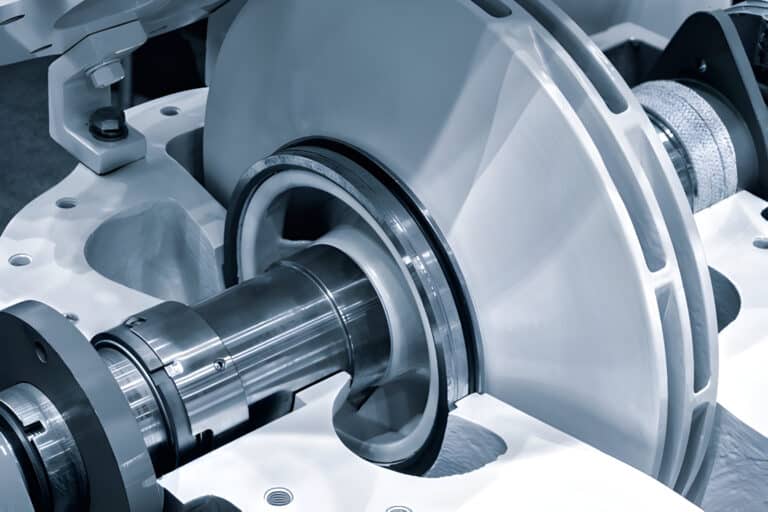

Seal water serves three critical functions that keep mechanical seals operating. It cools the seal and shaft, preventing thermal damage from friction. It lubricates the seal faces, creating the thin fluid film that prevents metal-to-metal contact. It flushes away impurities that would otherwise cause abrasive wear.

The pressure matters as much as the flow. Seal water must maintain a pressure differential—typically 15 psig (pounds per square inch gauge) above the seal chamber process pressure according to API Plan 54 industry standards. This positive pressure accomplishes something essential: it creates a one-way barrier that keeps process fluid contained inside the pump while seal water flows outward.

Think of it like a dam. The seal water acts as a dam holding back the process fluid. When pressure is right, nothing gets through. The seal faces stay separated by a microscopic fluid film, and friction stays minimal. When pressure drops, that dam leaks. When pressure spikes, the dam cracks.

What Happens When Seal Water Pressure Is Too High?

Running seal water at excessive pressure creates a chain reaction of damage. Here’s exactly what unfolds.

Seal Face Damage and Cracking

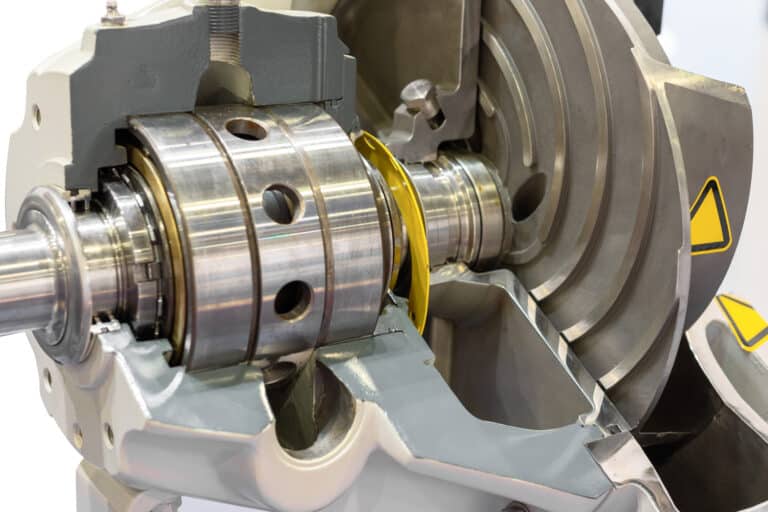

High pressure forces seal faces apart more aggressively than their design tolerates. The spring mechanism that maintains seal closing force works against this excessive pressure, creating uneven stress distribution across the faces.

When pressure finally normalizes or drops, the seal faces slam back together with violent impact. That collision generates micro-cracks across ceramic or carbon seal faces. These cracks spread under continued pressure cycling, eventually causing catastrophic seal failure. Engineers examining failed seals from high-pressure systems routinely find characteristic chip patterns and spalling damage radiating from impact points.

Accelerated Wear and Heat Generation

Every pound of excess pressure increases friction between seal faces proportionally. High-pressure seals generate heat that shouldn’t exist, raising seal chamber temperatures beyond design specifications.

Material degradation accelerates at elevated temperatures. Elastomeric components begin to harden and lose flexibility. Seal face materials degrade and lose their smooth polished finish, increasing friction further in a destructive feedback loop. A seal that should last three to five years under proper pressure management often fails in three to six months under consistently high pressure.

Seal Leakage and Secondary Damage

Leakage rates increase directly with pressure. Doubled pressure approximately doubles the leakage rate. This might seem like a small problem until you consider the downstream consequences.

Fluid loss means environmental contamination—your seal water or process fluid now escapes into surrounding equipment. That escaped fluid reaches pump bearings, corrodes shaft surfaces, and damages structural components never designed for liquid exposure. Replace a $500 seal now, or rebuild a $50,000 pump assembly later.

Increased System Costs

Every pressurization dollar eventually costs you money. Higher pressure means higher water consumption. Frequent seal replacements from accelerated wear multiply labor costs and parts expenses. Contaminated process fluid from leaking seals requires water treatment or disposal, adding compliance costs.

Plants running excessive seal water pressure typically see repair bills that would pay for proper monitoring systems five times over.

What Happens When Seal Water Pressure Is Too Low?

Low seal water pressure creates a different nightmare: contamination and catastrophic failure.

Contamination of Process Fluid

When seal water pressure drops below process pressure, the seal water dam fails. Process fluid begins creeping backward into the seal water circuit. That contamination happens silently—you won’t notice until damage is extensive.

Contaminated seal water loses its effectiveness. It can’t cool properly if it contains process fluid with different thermal properties. It can’t lubricate if suspended particles cause abrasive wear. Each pump cycle further contaminates the seal water with process impurities, creating a vicious cycle of degradation.

Cavitation and Seal Failure

Low suction pressure in the pump leads to cavitation—a condition where fluid vaporizes at the low-pressure zone, creating bubbles that collapse violently. That bubble collapse generates shock waves powerful enough to deform the pump shaft.

Shaft deflection means the seal no longer aligns properly. Seal faces that should maintain perfect parallelism now contact unevenly, creating localized pressure points. Sudden, catastrophic seal failure follows quickly. This isn’t gradual wear—it’s sudden destruction.

Reduced Lubrication and Rapid Wear

Inadequate pressure limits seal water flow through the sealing interface. The fluid film between seal faces becomes too thin to protect them. Metal-to-metal contact occurs instead of smooth fluid separation.

Wear accelerates dramatically under these conditions. Seal faces develop rough spots and score marks. Within weeks of low-pressure operation, a seal develops damage that should take years under proper conditions.

System Performance Degradation

Low seal water pressure compromises the entire system. Pump efficiency drops as bearings receive inadequate lubrication. Vibration increases as worn seals allow shaft movement. Noise levels rise to alert operators that something is wrong.

Connected equipment downstream suffers from inconsistent output pressure and flow rate. Your system reliability becomes unreliable—exactly the opposite of what industrial equipment should deliver.

How to Identify Pressure Problems: Warning Signs

Catching pressure problems early saves thousands in repair costs. These warning signs tell you something is wrong.

Visual Indicators

Visible leakage around the seal housing screams that pressure control failed. Discoloration or deposits on seal surfaces indicate thermal stress or chemical reaction. Finding oil or process fluid contamination in the seal water circuit confirms that the pressure barrier broke down.

Look closely at the seal faces themselves if you get the chance. White or crystalline deposits, burn marks, or scoring patterns all point to pressure-related stress.

Performance Indicators

Unusual pump vibration develops when seal alignment degrades. Strange noise—squealing, grinding, or high-pitched sounds—often signals seal distress before complete failure. Temperature rise in the seal chamber shows excessive friction from pressure imbalance or cavitation damage.

Changes in flow rate or output pressure suggest internal seal damage affecting pump performance. If your pump previously delivered consistent output and suddenly shows variation, suspect seal pressure problems.

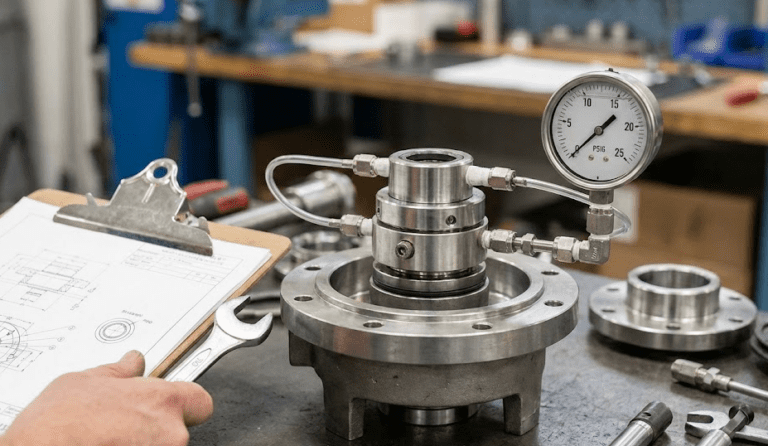

Measurement and Diagnosis

Invest in calibrated pressure gauges and measure seal water pressure regularly. Place gauges at the seal water supply point and the seal chamber return to catch differential pressure. Compare your readings to manufacturer specifications for your specific seal model and API plan.

Don’t assume a single reading tells the whole story. Pressure that spikes only during high-flow operation could indicate a regulator problem. Steady low pressure suggests filter clogging or pump inadequacy. Pressure that fluctuates wildly indicates system instability—possibly air entrainment or regulator hunting.

Pressure spikes lasting seconds might be normal pump startup transients. Chronic pressure above or below specification requires investigation and correction.

When to Call a Professional

Certain situations exceed do-it-yourself troubleshooting. When pressure fluctuates unexpectedly despite apparent regulation, a professional should investigate your regulator and system response.

Recurring seal failures despite pressure monitoring and maintenance point to systemic problems—possibly incorrect seal selection, misaligned shaft, or cavitation issues unrelated to pressure. Pressure management alone won’t fix those problems.

When multiple system components show wear—vibration, noise, temperature rise, and pressure problems all occurring together—you’re likely facing secondary damage from a primary failure. A professional can diagnose root cause rather than treating symptoms.

If you can’t maintain specified pressure range despite all adjustment attempts, your system may need redesign—larger cooler, better regulator, or complete pressure support system replacement.

Conclusion

Seal water pressure balance is the difference between seals that last years and seals that fail in months. Get the pressure right and your mechanical seals deliver reliable, cost-effective operation. Get it wrong and you’re guaranteed expensive failures, extended downtime, and frustrated maintenance teams.

Start today by measuring your current seal water pressure. Compare it to manufacturer specifications for your specific seal and API plan. If you’re running outside specification, identify and correct the problem immediately. Implement regular monitoring—either manual or automated—and you’ll prevent the costly seal failures that plague systems with poor pressure management.

Your seals have only two job requirements: stay cool and stay lubricated. Give them the right pressure to do both, and they’ll reward you with years of reliable service.