The difference between a seal that lasts 12 months and one that runs for 3+ years often comes down to selection. High-pressure applications above 200 PSIG demand specific technical criteria that many plant managers overlook. Get them right, and you’ll dramatically cut maintenance costs. Get them wrong, and you’re looking at frequent repairs, safety risks, and lost production.

To select a mechanical seal for a high-pressure pump, you need to evaluate five critical factors: operating pressure and temperature, process fluid properties, seal configuration (balanced vs. unbalanced, single vs. dual), face material compatibility, and the appropriate API flush plan.

Why Does High Pressure Demand Special Seal Considerations?

High-pressure pumping creates hydraulic forces that can destroy seals designed for standard service.

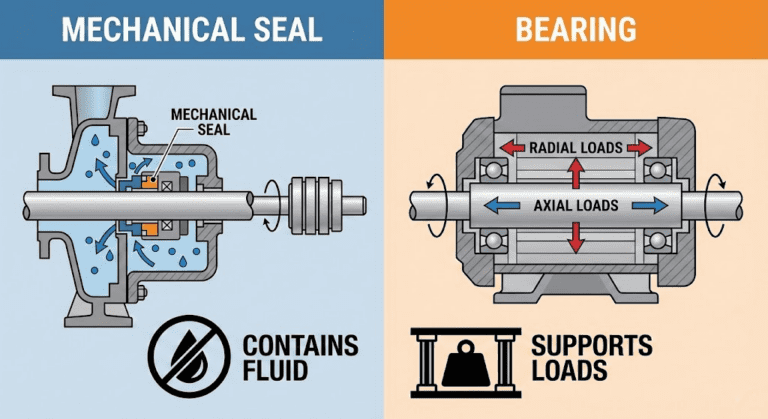

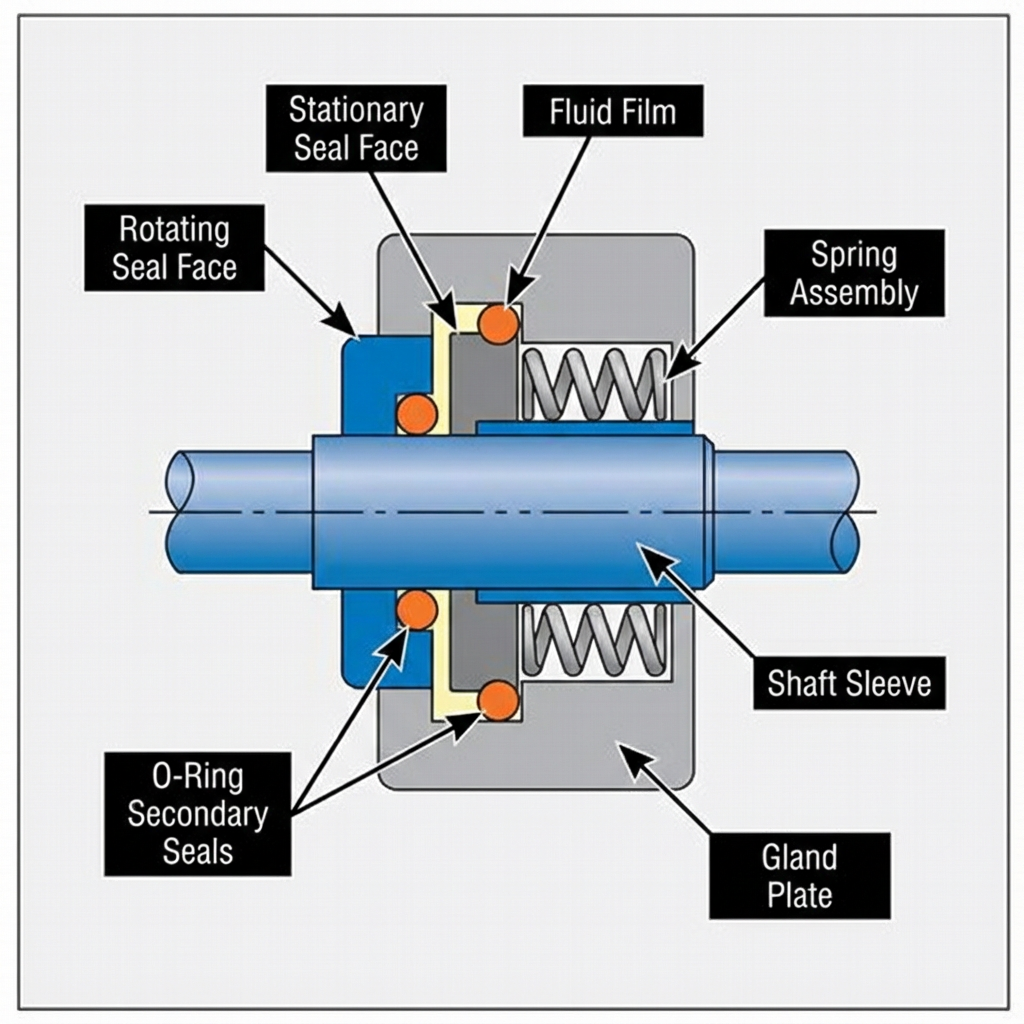

A mechanical seal works by maintaining contact between two precision-lapped faces—one rotating with the shaft, one stationary in the housing. The fluid pressure pushes these faces together.

At low pressures, this works fine. But crank up the pressure past 200 PSIG, and physics starts working against you.

The hydraulic force pushing the faces together increases proportionally with pressure. More force means more friction. More friction means more heat. And excessive heat is what kills mechanical seals.

An unbalanced seal at 500 PSIG experiences crushing loads on its faces. The seal overheats, the lubricating film between the faces breaks down, and you get rapid wear or catastrophic failure. I’ve seen unbalanced seals in high-pressure service fail within weeks.

The 200 PSIG threshold is your dividing line. Below it, standard unbalanced seals work well. Above it, you need balanced designs specifically engineered to handle the hydraulic forces.

What Are the Key Selection Criteria for High-Pressure Mechanical Seals?

Selecting the right seal starts with matching it to your actual operating conditions—not just the design point, but the full range of pressures, temperatures, and fluid properties your pump will see.

How Do Operating Conditions Determine Seal Type?

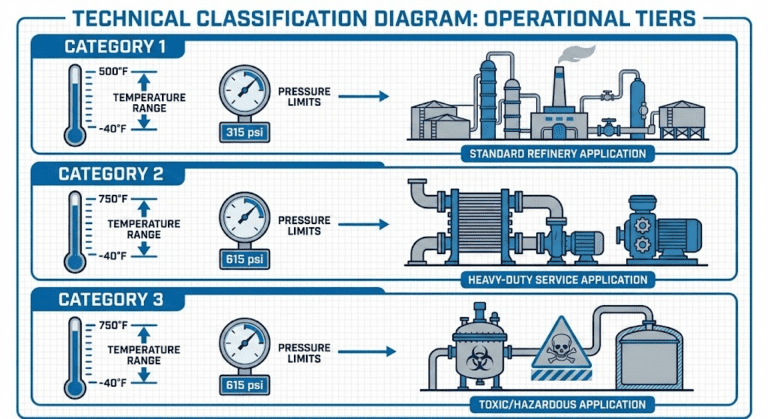

Your operating pressure dictates the seal design category. Here’s the breakdown:

| Pressure Range | Recommended Seal Type | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Below 200 PSIG | Unbalanced single seal | Cooling water, general service |

| 200-500 PSIG | Balanced single seal | Process pumps, moderate duty |

| 500-1,500 PSIG | Balanced dual seal | Boiler feed, high-pressure process |

| Above 1,500 PSIG | Dual-stage with pressure breakdown | Pipeline pumps, critical applications |

What Is the Difference Between Balanced and Unbalanced Seals?

The hydraulic balance ratio is what separates high-pressure seals from standard ones. Think of it like load distribution.

In an unbalanced seal, the full fluid pressure acts on the seal face area. More pressure means proportionally more closing force. At high pressures, this force becomes excessive—generating heat, accelerating wear, and potentially distorting the faces.

A balanced seal uses clever geometry to reduce the effective area exposed to pressure. The faces experience only a fraction of the hydraulic load, regardless of system pressure. This means less friction, less heat, and longer life.

Here’s a practical comparison: cooling water systems typically operate at 50-150 PSIG. Unbalanced seals work fine there. But high-pressure boiler feed pumps at 500+ PSIG absolutely require balanced designs.

Which Seal Configuration Should You Choose for High-Pressure Service?

Beyond balanced vs. unbalanced, you need to decide between single and dual seal arrangements.

When Is a Single Seal Sufficient?

A well-designed balanced single seal handles many high-pressure applications effectively.

Single seals work when the process fluid provides adequate lubrication, isn’t hazardous or environmentally sensitive, and when some minor leakage (typically measured in drops per hour) is acceptable. Most industrial water services, clean oil applications, and non-hazardous chemical processes fall into this category.

The key to single seal success in high-pressure service is the throttle bushing (also called a throat bush). This component sits behind the seal and creates a restriction between the pump chamber and the seal area. By controlling flow, it reduces the pressure the seal faces actually see.

When Should You Specify Dual Mechanical Seals?

Dual seals become necessary when single seals can’t meet safety or reliability requirements. You should specify dual seals when:

- The process fluid is hazardous, toxic, or flammable—leakage creates safety risks

- Zero emissions are required for environmental compliance

- Seal chamber pressure exceeds 500 PSIG consistently

- The process fluid has poor lubricity and needs barrier fluid for face cooling

- Extreme reliability is essential—unplanned downtime isn’t acceptable

Dual seals use a barrier or buffer fluid between two seal sets. This fluid provides lubrication, cooling, and a secondary containment layer. If the inboard seal fails, the barrier fluid prevents process release while the outboard seal maintains containment.

What Are the Dual Seal Arrangement Options?

Dual seals come in three main arrangements, each suited to different conditions.

Back-to-back arrangement places the seals facing opposite directions. This works with pressurized barrier fluid at higher pressure than the process. It’s the standard choice for high-pressure applications where you want maximum protection. The barrier pressure actively prevents process fluid from reaching the inboard seal faces.

Face-to-face arrangement has both seals facing inward. This uses buffer fluid at lower pressure than the process. It’s suitable when you want to contain process fluid and provide a safety backup, but don’t need the added complexity of pressurized barrier systems.

Tandem arrangement stacks both seals facing the same direction. This creates staged pressure reduction—the inboard seal handles most of the pressure, while the outboard seal provides backup containment. It’s used when pressurized barrier systems aren’t practical.

For high-pressure service above 500 PSIG, back-to-back with pressurized barrier is the most common and reliable choice.

How Do You Select the Right Face Materials?

What Are the Primary Face Material Options?

Three materials dominate high-pressure mechanical seal applications:

| Material | Hardness | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon Carbide (SiC) | 9.5 Mohs (near diamond) | Abrasive fluids, high temperatures to 2550°F | More brittle, higher cost |

| Tungsten Carbide (WC) | Extremely high | High pressure, impact/shock conditions | Susceptible to ammonia leaching |

| Carbon Graphite | Soft, self-lubricating | General service, paired with harder materials | Can’t handle abrasive media |

How Should You Pair Seal Face Materials?

The best seal face pairings balance hardness, thermal conductivity, and wear characteristics.

Silicon carbide + Carbon is the most tribologically effective pairing. The hard SiC face resists wear while the softer carbon conforms to minor imperfections and provides self-lubrication. This combination handles most high-pressure industrial applications well.

Tungsten carbide + Carbon is preferred when physical demands are extreme. The WC face resists distortion under high pressure better than SiC, making it ideal for very high-pressure service with clean fluids.

Silicon carbide + Silicon carbide is required when abrasive solids are present. The hard-on-hard pairing resists particle damage that would quickly destroy a carbon face. It’s the only choice for slurry or heavy particulate service.

Match your pairing to your actual conditions. A chemical plant pumping clean acid needs different materials than a mine dewatering pump handling slurry.

Which Secondary Seal Materials Work for High-Pressure Applications?

O-rings and elastomers are the seal’s secondary sealing elements. They prevent leakage paths around the primary faces and must withstand your process conditions.

Common elastomer choices include:

- EPDM: Good for water, steam, and many chemicals. Poor with hydrocarbons.

- Viton (FKM): Excellent for oils and hydrocarbons. Handles higher temperatures than EPDM.

- PTFE: Broadest chemical compatibility. Handles extremes but requires special designs due to lack of elasticity.

- Kalrez (FFKM): Premium material for the most demanding chemical and temperature requirements.

Temperature limits matter enormously. NBR (nitrile) in a 150°C environment hardens and cracks rapidly. Always verify your elastomer choice against actual operating temperatures, including startup and upset conditions.

Metal components—springs, retainers, and housing parts—need similar attention. Standard 316 stainless steel handles most industrial applications. Aggressive chemicals require specialty alloys like Alloy 20 or Hastelloy.

What API Flush Plan Do You Need for High-Pressure Service?

In high-pressure dual seal applications, the barrier fluid provides lubrication and cooling for the seal faces, maintains pressure differential across the seals, and creates a safety buffer between process and atmosphere.

How Do You Choose Between Plan 53 and Plan 54?

Plans 53 and 54 are the workhorses for high-pressure dual seal applications. Both provide pressurized barrier fluid, but they work differently.

| Criteria | Plan 53A/B/C | Plan 54 |

|---|---|---|

| Barrier Pressure | Up to 150 psi standard; higher with modifications | 100-1,000+ psi |

| System Type | Self-contained reservoir | External pump or central system |

| Heat Removal | Limited capacity | Superior (higher flow rates) |

| Complexity | Simpler | More complex |

| Initial Cost | Lower | Higher |

| Location Requirements | Must be near pump | Can be remote |

| Multiple Seals | One system per seal | Can serve multiple seals |

Plan 53 uses a self-contained reservoir pressurized with nitrogen. The seal’s internal pumping ring circulates barrier fluid through the reservoir. It’s simpler and cheaper—the right choice for most applications where barrier pressure requirements stay under 150 psi.

Plan 53B uses a gas-charged bladder accumulator that maintains pressure without direct gas-to-liquid contact. It’s a clever solution that’s become quite popular.

Plan 54 uses an external pump and reservoir to circulate pressurized barrier fluid. The external pump provides higher flow rates, better heat removal, and consistent pressure regardless of seal leakage. When barrier pressures exceed 200 psi, Plan 54 is typically required.

Plan 54 is also preferred when heat loads are high, multiple seals need support from a central system, or shaft speed limits internal pumping ring capability.

The most reliable pressurized plan for dual seals? Plan 54, when properly maintained. The external pump and monitoring systems provide better control than self-contained options.

Making the Right Choice

Involve seal manufacturers early in the design process. Provide complete operating data, including off-design conditions. Specify API 682 compliance for critical applications. And budget for proper flush plan support—it’s not the place to cut costs.

The mechanical seal is often called the weakest link in a pump. But with proper selection, it doesn’t have to be. Get the fundamentals right, and your high-pressure pumps will run reliably year after year.