“Even after replacing a seal, the new seal started leaking a few weeks later. The seals were spec’d for systems with over 30% glycol, and the system had 35%.”

I hear this frustration from technicians regularly. They follow the spec sheet, install the seal correctly, and within weeks they’re back at the same pump with the same problem. The most common mistake I see is treating chiller pump seals like any other pump seal. They’re not.

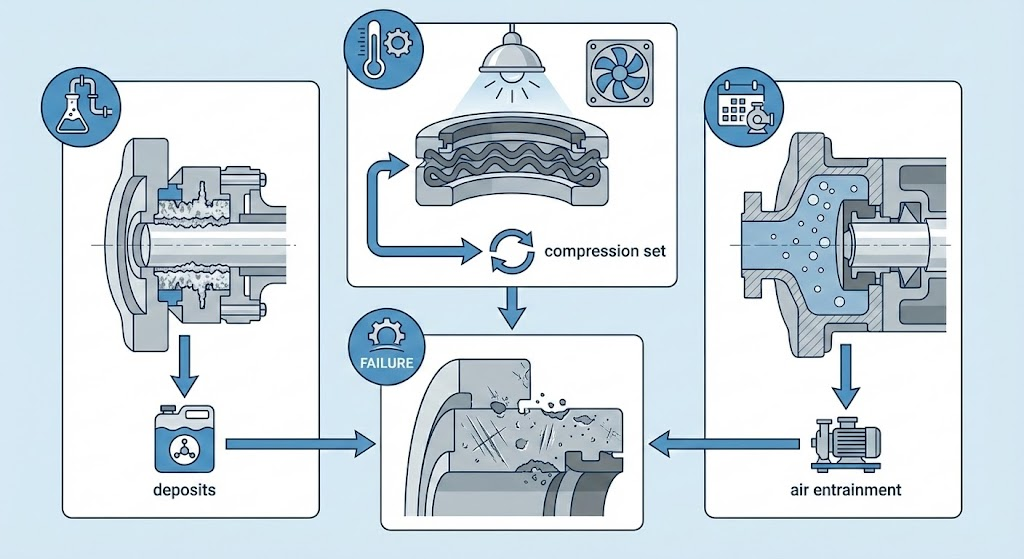

Chiller systems have three unique failure patterns that generic troubleshooting guides miss entirely: glycol chemistry issues, thermal cycling stress, and seasonal startup procedures. Address these three root causes and you’ll prevent the majority of premature seal failures in HVAC chiller applications.

Why Chiller Pump Seals Fail Differently Than Other Pump Seals

Chiller pump seals operate in conditions that other pump seals rarely encounter. The glycol/water mixture changes surface tension and lubrication behavior compared to pure water. Seasonal operation means extended shutdowns followed by sudden demands. Temperature swings between ambient and chilled operating temps stress elastomers in ways that constant-temperature applications never do.

According to Reliabilityweb, seal-related repairs represent approximately 60 to 70% of all centrifugal pump maintenance work. In chiller applications, that percentage skews even higher because the operating conditions compound problems that would be minor in simpler systems.

A facility in Texas ran three Multistack chillers with Armstrong pumps. All primary pumps across the three units started leaking. Replacement seals failed within weeks. The seals were rated for 30%+ glycol, and the system ran 35%. On paper, everything matched. In reality, three factors combined to defeat every seal they installed: propylene glycol’s lower surface tension, additive plating from non-industrial coolant, and air locks in the seal chamber during startup.

Glycol Chemistry Issues – The Hidden Seal Killer

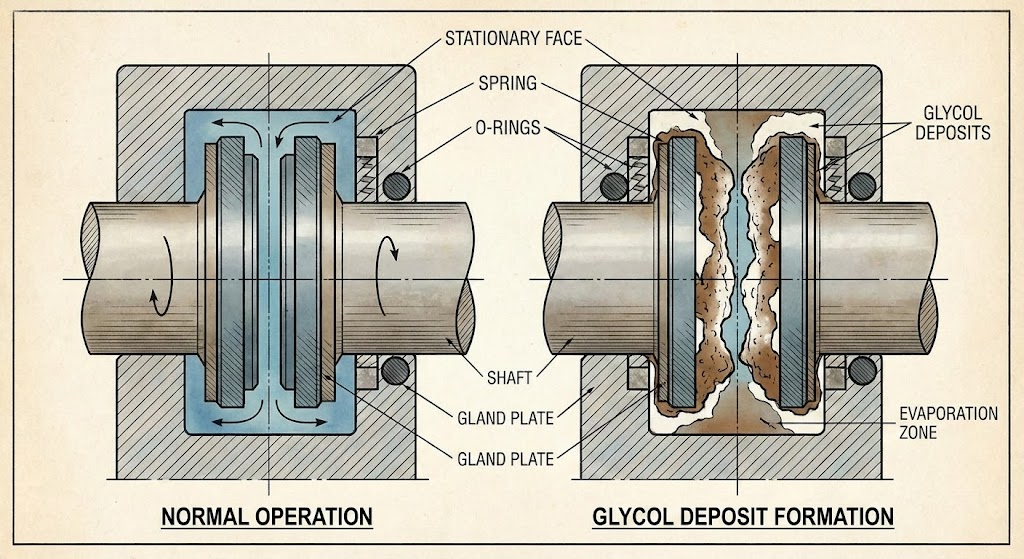

Glycol additives and concentration cause deposits on seal faces that prevent the fluid film from forming properly. The mechanism is straightforward: when glycol boils or evaporates between seal faces during brief upset conditions, it leaves residue behind. Silicate inhibitors from automotive antifreeze are particularly problematic because they plate onto the faces and create uneven gaps that lead to leakage.

The tendency to leave deposits gets worse as the concentration of glycol in water exceeds about 60%. Below that threshold, deposits form slowly and may self-clean. Above it, the deposits accumulate faster than they clear.

If you’re using automotive antifreeze in your chiller system, stop reading and fix that first. Automotive anti-freeze should not be used in barrier or buffer fluid systems. Only pure ethylene glycol or propylene glycol should be used. The additives in automotive products cause high wear on seal faces and reduce reliability regardless of how well you manage everything else.

Beyond additive chemistry, the type of glycol matters for sealing. Propylene glycol in chilled water systems is reportedly more leaky than ethylene glycol because ethylene has higher surface tension. That higher surface tension helps the fluid bridge microscopic gaps in the seal interface. Propylene glycol’s lower surface tension means smaller gaps can break through as leak paths.

This creates a practical dilemma. Propylene glycol is FDA-approved for incidental food contact and safer if the system serves occupied spaces. Ethylene glycol seals better but is toxic. My recommendation: if your application allows ethylene glycol, use it and monitor more closely. If you must use propylene, expect higher baseline leakage and consider tighter seal face specifications.

Glycol Testing Parameters to Check

Before you order another replacement seal, test your glycol:

| Parameter | Target Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Concentration | 25-35% | Standard for most commercial systems |

| pH | 8.0-10.0 | Below 8.0 accelerates corrosion |

| Conductivity | Under 400 ppm (standard) | Glycol-rated seals (EPR/SiC) tolerate up to 20,000 ppm |

| Fluid age | Under 3-5 years | Replace when fluid consistently fails testing |

Testing should be done at least twice a year, and more frequently in high-demand systems. Uninhibited ethylene glycol is significantly more corrosive toward carbon steel than plain water, so pH degradation from inhibitor depletion can damage metal components well before the seal faces show problems.

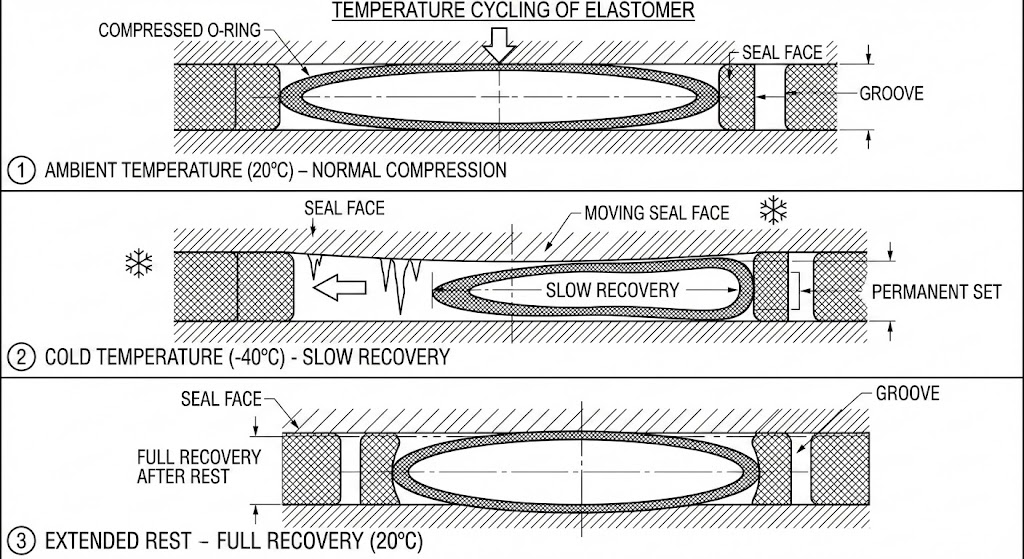

Thermal Cycling Stress – Why Seals Leak When Temperature Drops

Elastomer behavior changes near the material’s glass transition temperature. A chilled water pump with a Crane type 3710 seal showed a pattern that puzzled the maintenance team: leak-free until water temperature dropped below 50F, then leaking. The leak persisted even after the water warmed back to 70F. Only overnight idle restored the seal.

The explanation lies in how fluorocarbon elastomers respond to cold. When cooled near (but not beyond) their glass transition temperature, the cold O-ring takes longer than normal to return to its original shape after being compressed. The seal face movement during thermal cycling compresses the O-ring, but the cold elastomer doesn’t spring back fast enough to maintain contact. It needs hours of rest at warmer temperatures to recover.

This failure mode doesn’t appear in seal manufacturer specs because the published temperature limits address chemical compatibility, not mechanical recovery behavior. The seal might be rated to -20F for chemical stability but leak at 45F due to elastomer response lag.

For chiller applications with aggressive temperature swings, select elastomers with lower glass transition temperatures than your minimum operating temperature. EPDM handles low temperatures better than FKM in many chilled water applications. On the hard face side, silicon carbide generally offers better heat checking resistance than tungsten carbide due to its superior thermal conductivity.

I see more thermal cycling failures from improper elastomer selection than from wrong face materials. The face materials get all the attention during specification, but the elastomer does the moment-to-moment work of maintaining contact during temperature swings.

Visual Signs of Thermal Stress

Heat checking appears as radial cracks on seal faces, looking like spokes on a wheel starting from the center and extending outward. Dry running is the primary cause because it eliminates the cooling and lubricating fluid film between faces. But in chiller applications, thermal cycling can produce similar patterns even with adequate lubrication because the faces expand and contract at different rates during temperature changes.

Seasonal Startup Procedures – The Make-or-Break Moment

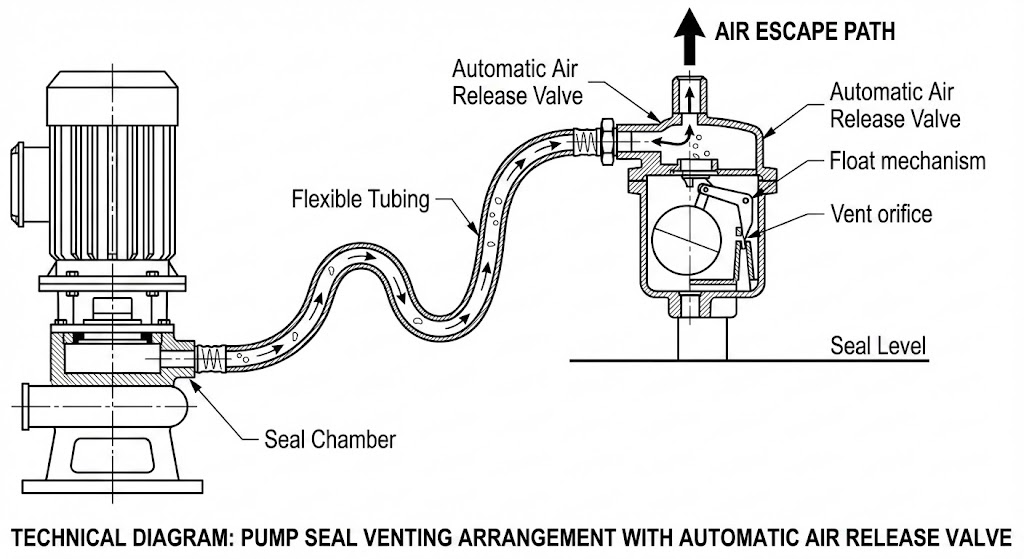

Improper startup after seasonal shutdown causes dry running and thermal shock that damage seals within minutes. A case study from East Kentucky Power’s Spurlock Station documented chronic seal leaks traced to one overlooked detail: no venting arrangement. Air accumulated in the seal chamber during shutdown and couldn’t escape during startup.

The solution came from an unexpected source. A reader from the Town of Amherst, NY shared that automatic air release valves with float mechanisms had successfully reduced seal failures in their vertical pump installations. The simple addition of a vent path eliminated their repeat failures.

A North Sea oil platform faced repeated seal failures across 40 pumps. The reliability investigation identified 12 distinct issues, but incomplete venting during startups topped the list. Every startup procedure that skipped the venting step added cumulative damage. Over three years, the pattern became catastrophic.

Chiller pumps not on VFDs may experience these issues because VFDs would give the pumps a soft start rather than an immediate 0-100% start. The sudden acceleration creates hydraulic shock and thermal stress at the seal faces. If you don’t have a VFD, you need to compensate with procedure.

My startup checklist for seasonal commissioning:

- Verify glycol concentration and pH before energizing

- Open all vents and leave open until steady flow (no air bubbles)

- Hand-rotate shaft to verify free movement

- If no VFD: start pump, run 30 seconds, stop, wait 2 minutes, repeat twice before continuous operation

- Check for leaks at operating temperature, not just at startup

If you skip the venting step, you’ll be back in a week replacing another seal.

Diagnostic Process – Start With the System, Not the Seal

Most technicians start with the wrong thing. They pull the pump, inspect the seal, and decide whether to repair or replace based on what the seal looks like. But the seal’s appearance tells you what happened, not why it happened. If you replace a seal without checking glycol chemistry, you’re just installing the next failure.

Before you touch the pump:

System checks first:

- Glycol concentration and pH (lab test, not refractometer alone)

- Operating pressure and temperature logs from the past month

- Vibration readings if available

- Any recent changes to the chiller plant operation

Operating condition verification:

- Is the pump running at or near best efficiency point?

- Has the flow changed due to valve adjustments or fouling?

- Is the suction pressure adequate (check NPSH margin)?

Only after ruling out system issues should you proceed to seal inspection. Then the physical evidence becomes meaningful:

Seal face interpretation:

| Pattern | Likely Cause |

|---|---|

| Heat checking (radial cracks) | Dry running or thermal cycling |

| White/gray deposits | Glycol silicate buildup |

| Blistering on carbon face | Lubrication loss, inadequate flush |

| Uniform wear | Normal operation (this is good) |

| Localized wear | Misalignment or vibration |

Looking at damaged seals, if the elastomer has melted, the seal got very hot – most likely from dry running, though it could also be caused by the rotating and stationary faces seizing. Melted elastomer always points to thermal failure, and thermal failures almost always trace back to either startup procedure or operating condition issues.

One case from a temperature-controlled warehouse with a Goulds 3196 pump showed catastrophic seal failure less than a year after replacement. Investigation found tight 90-degree elbows instead of gentle slopes and substantial misalignment. That’s not a chiller-specific failure – it’s basic installation quality. Not every chiller pump seal failure comes from glycol or thermal cycling. Sometimes the root cause is mechanical, and standard troubleshooting applies.

When to Repair vs Replace – And When Neither Will Fix It

A properly maintained seal should last at least 2 years at published operating limits, with 3 years typical for API 682 specifications. Seal life well in excess of three years is possible for the majority of applications when root causes are addressed.

If your chiller seals aren’t reaching 2 years, the answer isn’t a better seal. It’s better system management.

But some facilities have given up on traditional seals and are converting systems to seal-less pumps – either mag drive or canned motor designs. This makes sense when:

- Glycol chemistry can’t be controlled (multiple building loops with unknown water treatment)

- Startup procedures can’t be enforced (many operators, no standardization)

- The cost of repeated failures exceeds the premium for seal-less equipment

Double mechanical seals (Plan 53A or 54 configurations) offer another option. They provide a buffer or barrier fluid that isolates the seal faces from the process fluid entirely. For chronic glycol chemistry problems, the double seal eliminates the root cause rather than tolerating it.

Here’s a trick that saves time: before committing to a double seal upgrade, try industrial-grade glycol and documented startup procedures for two seasons. Double seals cost 2-4x more than single seals and add maintenance complexity with their reservoir systems. They’re worth it when root causes truly can’t be fixed, but they’re overkill if basic glycol management solves the problem.

Next Step: Test Before You Order

The next time you face a chiller pump seal failure, resist the urge to order a replacement seal immediately. Instead:

- Pull a glycol sample and send it for full analysis (concentration, pH, conductivity, reserve alkalinity)

- Review startup logs – was proper venting documented?

- Check temperature records for the week before failure – any unusual swings?

Most chiller seal failures I troubleshoot trace back to one of the three patterns covered here. The seal replacement that finally works is usually the one installed after the real root cause gets addressed. Start with the system, not the seal, and your success rate will improve dramatically.