Carbon seals show up in over 90% of industrial pump applications. You’ve probably encountered them dozens of times without thinking twice about how they actually work.

Here’s the short answer: a carbon seal is a mechanical sealing device that uses carbon graphite material pressed against a rotating shaft collar to prevent fluid or gas leakage. The carbon ring stays stationary while a spring keeps it pressed against a rotating mating surface.

How Does a Carbon Seal Work?

A carbon seal creates a tight, low-friction barrier between rotating and stationary surfaces by using spring pressure to maintain constant contact between two precision-machined faces.

The mechanism is straightforward once you break it down into components.

Understanding the Basic Components

Every carbon seal has four essential parts working together.

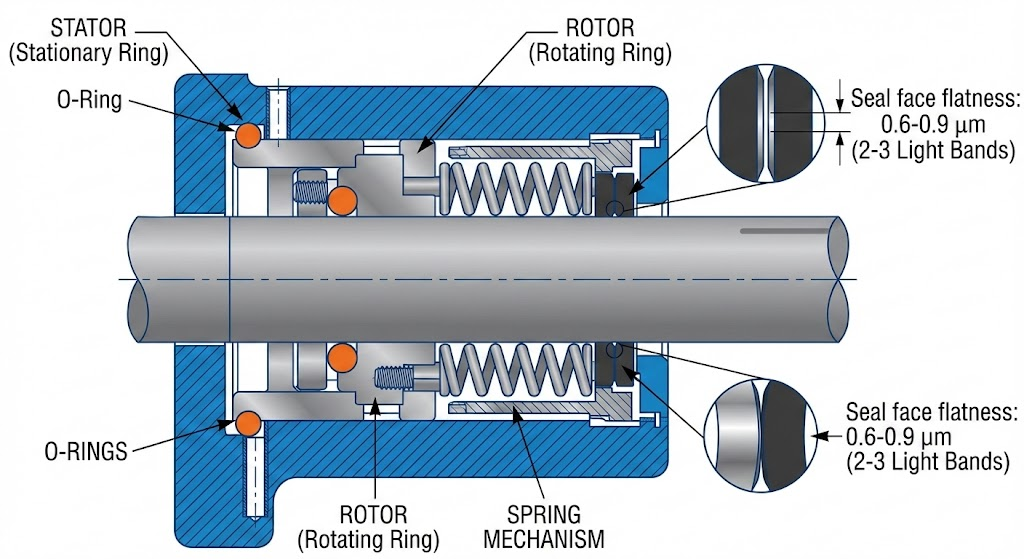

The stator is the stationary ring that gets sealed to the pump housing through an O-ring. It doesn’t move. The rotor is the rotating ring sealed to the shaft, also via an O-ring. It spins with the shaft.

Between these two, you’ve got spring or bellows systems that provide axial compression. This spring pressure is critical. It keeps the faces in contact regardless of wear or minor dimensional changes.

Both seal faces are polished to an incredibly flat surface, typically 2-3 Light Bands (that’s 0.6-0.9 micrometers for those keeping score). To put that in perspective, you’re looking at a flatness tolerance thinner than a human hair by a factor of 100.

The Sealing Mechanism in Action

When the pump starts, here’s what happens.

The spring maintains constant contact force between the rotating and stationary faces. As the shaft spins, a thin fluid film forms between the seal faces. This film is essential. It lubricates the contact zone and carries away heat.

Carbon’s self-lubricating properties kick in immediately. The graphite grains in the carbon material slide over one another thanks to their unique layered molecular structure. Think of it like a deck of cards. Each layer slides easily across the next.

This is why carbon works so well where other materials would grind themselves to pieces.

How Self-Lubrication Occurs

The magic is in the material composition. A typical carbon seal face uses an 80% carbon / 20% graphite blend ratio.

Graphite has a laminar structure. Imagine stacking sheets of paper. The bonds between sheets are weak, so they slide past each other with minimal resistance. That’s essentially what graphite grains do at the molecular level.

During initial operation, the carbon face experiences some wear. This creates very fine carbon particles that are extremely reactive. These particles bond together and form a protective carbon-particle layer on both the carbon face and the mating counterface.

This burnished film acts as a solid lubricant. It’s self-renewing too. As the seal operates, the film maintains itself through continuous microscopic transfer of material.

What Are the Different Types of Carbon Seals?

Three main types dominate industrial applications, each designed for specific operating conditions.

Carbon Graphite Mechanical Seals

These are the workhorses. You’ll find carbon graphite mechanical seals in pumps and rotating equipment across every industry.

The design pairs a carbon face with a significantly harder mating material like silicon carbide, tungsten carbide, or ceramic. This hard/soft combination minimizes friction while maximizing wear resistance.

You can get them in single face arrangements, where one carbon face seals directly against one hard face. Double face arrangements use two carbon faces interlocking with each other for applications requiring higher sealing integrity. Chemical processing plants often specify double seals for hazardous fluids.

Carbon Ring Seals

Carbon ring seals use a different approach. Instead of a continuous ring, they consist of segmented carbon rings bound together by a garter spring.

These work particularly well for non-hazardous gases like air, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide. The segmented design allows the rings to follow shaft radial movement when the equipment passes through critical speeds.

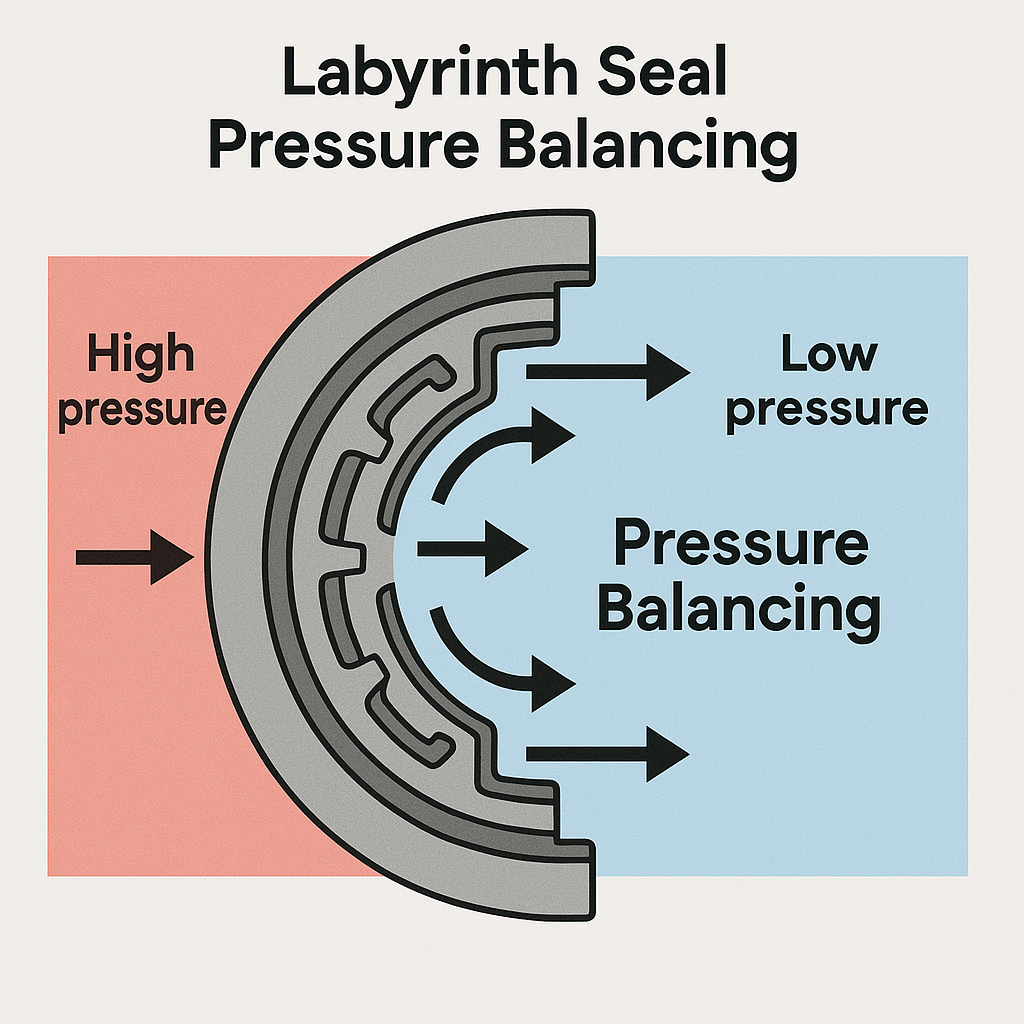

The result? Lower leakage than labyrinth seals with the added benefit of being able to operate at closer clearances than bearing clearances allow. The trade-off is that carbon rings need periodic replacement because they do experience rubbing contact.

Impregnation Types

Not all carbon seals are created equal. The impregnation material dramatically affects performance.

| Impregnation Type | Best Applications | Temperature Range | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resin (Phenolic/Epoxy) | Standard applications | Up to 200°C | Cost-effective, broad chemical compatibility |

| Antimony Metal | High temp/pressure, API 682 | Up to 350°C | Superior dry-running, better thermal conductivity |

| Electrographite | Extreme temperatures | Up to 538°C | Maximum thermal stability |

Resin-impregnated carbon is your standard grade. It handles most applications well and won’t break the budget. The resin fills the porous carbon structure, reducing leakage paths and improving strength.

Antimony-impregnated carbon is the heavy hitter. The resin carbon couldn’t handle the high-pressure, high-temperature conditions. Once they switched back to antimony impregnation, the problem disappeared.

For extreme temperatures above 400°C, electrographite is your only option. The graphitization process heats carbon graphite above 2200°C (4000°F) in a controlled atmosphere. This reorganizes the amorphous carbon into a highly organized graphene-layered matrix with exceptional thermal stability.

What Materials Are Carbon Seals Paired With?

The mating material choice can make or break your seal’s performance. Get this wrong, and you’re looking at premature failures and unplanned downtime.

Why Does Mating Material Selection Matter?

Carbon is the “soft” wearing face in most configurations. That’s intentional. By pairing soft carbon with a harder counterface, you get lower friction and a self-polishing effect that maintains excellent surface finish over time.

The counterface surface finish is critical. Industry guidelines specify a roughness of 16 micro-inches (0.4 micrometers) or less. If the surface is rougher than that, the burnished film from the carbon can’t sustain itself. The carbon wears rapidly instead of building up that protective layer.

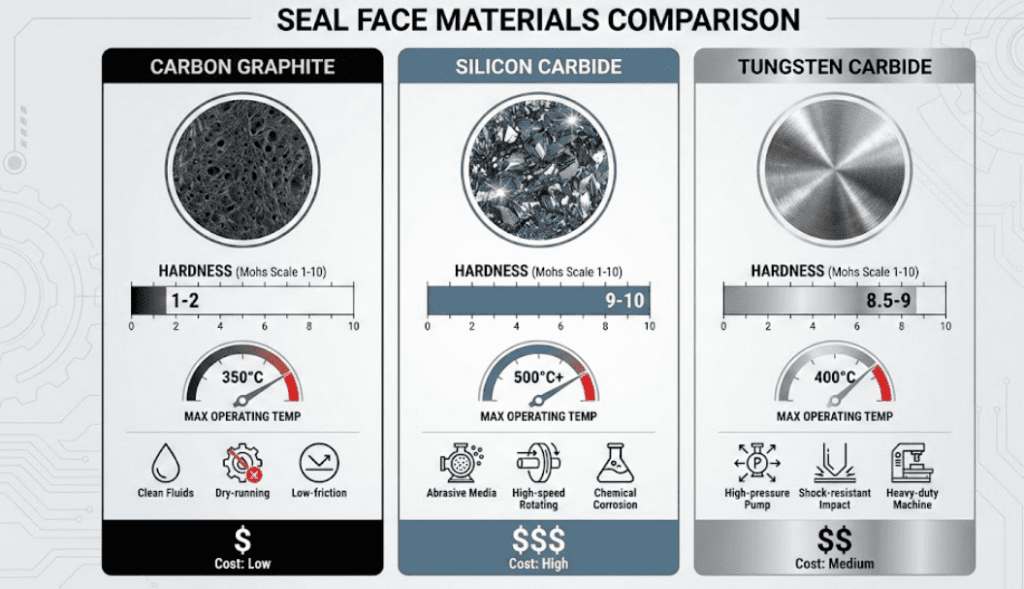

Carbon vs Silicon Carbide vs Tungsten Carbide

Here’s how the three main mating materials stack up:

| Property | Carbon Graphite | Silicon Carbide | Tungsten Carbide |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardness (Mohs) | 1-2 | 9-9.5 | 8-9 |

| Self-Lubricating | Yes | No | No |

| Max Temperature | 350°C | 500°C+ | 400°C |

| Chemical Resistance | Excellent (except oxidizers) | Excellent | Good |

| Best For | Clean fluids, dry running | Abrasive media, high temp | High pressure, impact |

| Relative Cost | Low | Medium-High | High |

Silicon carbide paired with carbon graphite is widely considered the best combination for most applications.

Silicon carbide’s hardness (9.5 on the Mohs scale, second only to diamond) makes it extremely wear-resistant. Its thermal conductivity is five times greater than carbon graphite, which helps dissipate heat from the sealing interface.

Tungsten carbide shines in physically demanding applications. It’s denser than silicon carbide and handles extreme pressure better.

What Are the Operating Limits of Carbon Seals?

Every seal material has limits. Push beyond them, and you’re asking for trouble. Carbon seals are remarkably versatile, but understanding their boundaries keeps equipment running.

| Parameter | Standard Carbon | High-Performance | Electrographite |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max Temperature | 200°C (392°F) | 350°C (662°F) | 538°C (1000°F) |

| Pressure Range | Vacuum to 100 psi | Up to 250 bar | Application-specific |

| PV Limit | 150,000 psi-ft/min | 200,000 psi-ft/min | Varies |

Mechanical seals in general can operate from -200°C to +450°C and handle sliding velocities up to 150 m/s. Carbon seals occupy a large portion of that range.

The PV limit (pressure times velocity) is a useful guideline. An upper PV limit of 200,000 psi-ft/min is commonly used for industrial unbalanced seals. For example, an inside seal using ceramic versus carbon graphite faces at 1,750 rpm might have a PV rating of 150,000 psi-ft/min with 150°F water, but 205,000 with light hydrocarbon oil.

What Should Engineers Consider When Selecting Carbon Seals?

Selection mistakes are expensive. A few extra hours spent on proper evaluation saves weeks of unplanned downtime.

Key Selection Criteria

- Process Fluid determines chemical compatibility requirements. What’s the viscosity? Does it contain solids? Will it provide adequate lubrication to the seal faces?

- Temperature affects everything. Standard carbon works to 200°C. Need more? Move to antimony impregnation or electrographite. Consider temperature excursions, not just steady-state operation.

- Pressure influences seal design and material selection. Steady-state pressure matters, but surge conditions can be even more critical. High-pressure applications may require antimony-impregnated carbon for the added strength.

- Speed directly affects the PV limit. Higher shaft RPM means more heat generation at the seal faces. Faster speeds may require harder mating materials or improved cooling.

- Environment around the seal matters. Oxidizing agents will attack carbon. Evaluate the atmospheric conditions, not just the sealed fluid.

- Reliability Requirements should drive decisions. What’s your target MTBF? How accessible is the equipment for maintenance? Critical applications justify higher-cost materials with longer life.

When Should Carbon NOT Be Used?

Sometimes carbon is the wrong choice entirely.

Media with solid particulates will erode the soft carbon face quickly. Carbon is brittle. Abrasive particles embed in the surface and grind away at the harder counterface. Switch to hard-on-hard pairs like silicon carbide versus silicon carbide.

Strongly oxidizing environments will chemically attack carbon. The carbon literally converts to CO and CO2 over time.

Color-sensitive applications like paper and paint production can experience contamination from carbon particles. The visual defects are unacceptable in finished products.

Hot oil applications with fugitive emission standards may require different materials. Some carbon grades don’t meet the strict emission requirements for volatile organic compounds.

Some deionized water applications can attack carbon. The aggressive nature of deionized water affects certain carbon grades more than others. Consult with your seal manufacturer for these applications.

Wrapping Up

Carbon seals prevent fluid leakage through a beautifully simple mechanism: self-lubricating carbon graphite faces maintained in contact by spring pressure. The graphite’s layered molecular structure creates a renewable protective film that minimizes friction and wear.

The material properties, mating pairs, and operating limits you’ve learned here give you the foundation for proper selection. Carbon pairs with silicon carbide handle most applications. Tungsten carbide steps in for high-pressure and high-impact situations. Temperature requirements determine whether you need resin, antimony, or electrographite impregnation.

Carbon remains the dominant seal face material in over 90% of industrial applications. That’s not changing anytime soon. Its unique combination of self-lubrication, chemical resistance, thermal stability, and cost-effectiveness makes it the default choice for good reason.

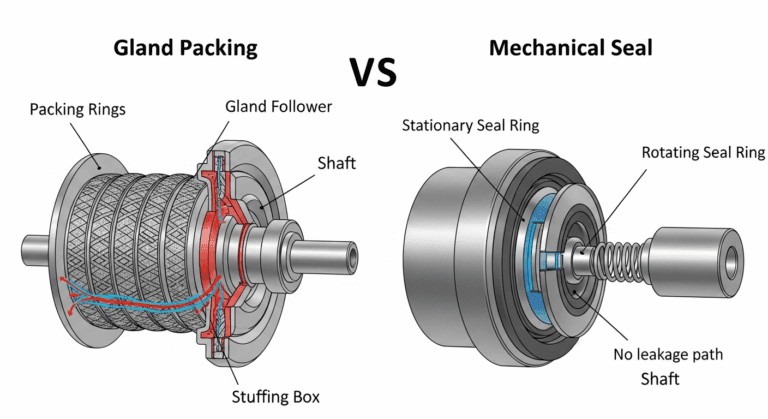

But it’s not universal. Evaluate alternatives like silicon carbide pairs for abrasive media, labyrinth seals for extreme temperatures, or packing for solid-laden fluids. The right seal for your application depends on your specific operating conditions, reliability requirements, and maintenance capabilities.