A U.S. Department of Defense study found that 80% of structural failures originated from corrosion pits commonly initiated from galvanic corrosion around fastener holes and dissimilar metal junctions. That statistic should change how you approach seal corrosion in marine seawater pumps.

Most corrosion prevention guides focus on chloride attack – selecting premium materials to resist the aggressive chloride ions in seawater. I’ve spent 15 years analyzing seal failure causes in marine applications, and the pattern tells a different story. The seals that fail fastest aren’t necessarily made from inferior materials. They’re assemblies where dissimilar metals create galvanic cells that accelerate corrosion far beyond what chloride alone could achieve.

Galvanic corrosion between dissimilar metals in seal assemblies causes more marine seawater pump failures than chloride attack alone. Standardizing your component metals and eliminating galvanic couples can prevent the majority of corrosion-related seal failures – often more effectively than upgrading to exotic alloys.

Why Galvanic Corrosion Dominates in Seawater Seal Assemblies

Seawater is a near-perfect electrolyte for galvanic corrosion. The high chloride content (approximately 19,000 ppm) and dissolved oxygen create ideal conditions for electrochemical reactions between dissimilar metals. Unlike fresh water, seawater’s conductivity allows galvanic currents to flow efficiently between metals even when they’re not in direct contact.

A mechanical seal assembly presents the worst-case scenario: multiple metals in intimate contact, all immersed in this aggressive electrolyte. Your typical assembly includes a stainless steel shaft sleeve, spring hardware, seal face holders, and the seal faces themselves – each potentially made from a different alloy with a different position on the galvanic series.

When these dissimilar metals contact each other in seawater, the less noble metal (anode) sacrifices itself to protect the more noble metal (cathode). This accelerates the corrosion rate on the anode far beyond what would occur from chloride attack alone. The driving force is the potential difference between the metals – the greater the separation on the galvanic series, the faster the attack.

What the spec sheet doesn’t tell you is the nickel binder in tungsten carbide creates a galvanic cell with your stainless steel components. According to the McNally Institute, galvanic corrosion can take place between a passivated stainless steel shaft or seal face holder and the active nickel in the nickel base tungsten carbide seal face. Active nickel is positioned far from passivated 316 stainless steel on the galvanic series chart – a significant potential difference that drives rapid attack.

The temperature at the seal face is higher than the bulk seawater temperature due to friction-generated heat. This elevated temperature accelerates the galvanic reaction, making seal faces particularly vulnerable. Higher temperatures can significantly increase the galvanic corrosion rate.

[Research published in ScienceDirect](https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1350630722006318 ) documented a case where 8 seal failures and more than 30 maintenance events occurred on 4 sulfuric acid pumps in only one year of service. Failure analysis determined that galvanic corrosion was mainly responsible for the failures. The differences in chemical compositions and microstructure between components played an important role in initiating the galvanic attack.

At dissimilar metal junctions, galvanic corrosion rates can reach 0.5 mm/year – far exceeding the baseline corrosion rate for stainless steel in seawater. This explains why seals fail in months when conventional corrosion would take years. A seal component losing 0.5 mm annually will be compromised within a year, while the same component in a unified-metal assembly might last a decade.

Material Selection: Voltage Thresholds and Unified Metals

Keep the potential difference between metals below 0.15V in seawater environments. Beyond this threshold, rapid galvanic attack occurs regardless of individual material quality. This 0.15V limit is significantly tighter than the 0.25V acceptable in controlled indoor environments – seawater is far less forgiving.

The following table shows galvanic series positions for common seal component materials in seawater:

| Material | Relative Position | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|

| Graphite | Most Noble (+0.3V) | Gaskets, packing (avoid in seawater) |

| Titanium | Noble (+0.15V) | Specialty hardware |

| Hastelloy C-276 | Noble (+0.1V) | Springs, bellows |

| 316L Stainless (passive) | Moderate (+0.05V) | Shafts, housings, holders |

| Silicon Carbide | Neutral (inert) | Seal faces |

| Tungsten Carbide (Ni binder) | Active nickel phase | Seal faces (problematic) |

| 304 Stainless (active) | Less Noble (-0.1V) | Avoid in seawater |

| Carbon Steel | Active (-0.4V) | Avoid in seawater |

Several key combinations to avoid:

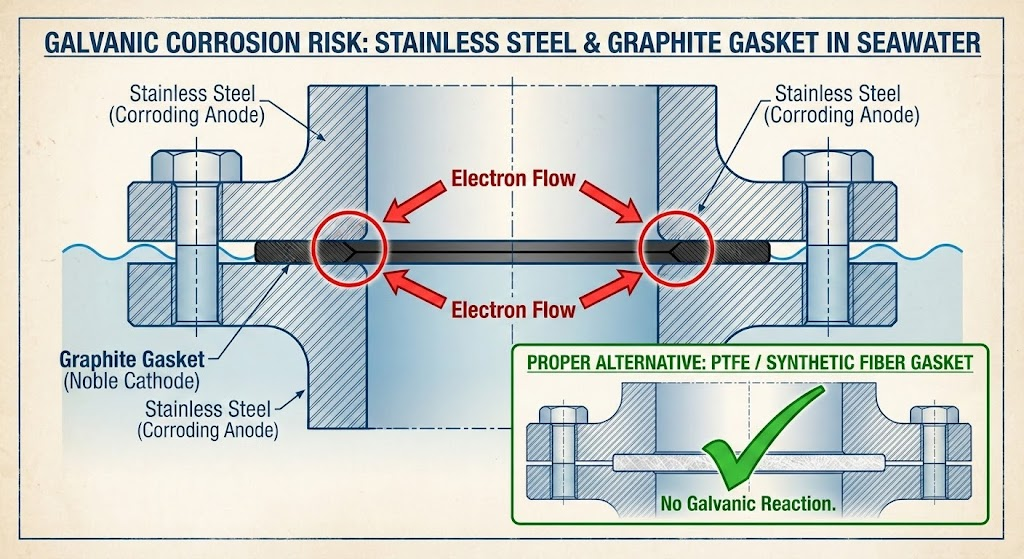

Graphite in contact with stainless steel creates a severe galvanic couple. Graphite acts as a noble cathode, driving accelerated corrosion of the stainless steel anode. The potential difference exceeds 0.25V – well beyond the 0.15V limit for seawater.

Tungsten carbide faces with stainless hardware – the nickel binder in WC becomes anodic to passivated stainless, corroding preferentially from within the face material. The face appears intact until the binder fails and carbide grains detach.

Mixed stainless grades – 304 and 316 in the same assembly create a potential difference that drives attack on the less noble 304. Even this “minor” mismatch causes problems in seawater’s aggressive environment.

I recommend silicon carbide over tungsten carbide for seawater not because of hardness, but because it has no metallic phase to attack. Silicon carbide is chemically inert with highly covalent Si-C bonds. Direct sintered silicon carbide contains no free silicon or metallic binders, making it galvanically neutral in seawater. When comparing SiC vs WC for mechanical seals, the galvanic consideration often matters more than the mechanical properties.

The unification principle offers more protection than material upgrade. Standardize all internal pump components to the same alloy family – 316L stainless for metal parts, or super duplex throughout if conditions demand it. A unified assembly of “inferior” 316L will often outlast a mixed assembly containing premium alloys, because you’ve eliminated the galvanic couples that drive the fastest attack modes.

A laboratory case illustrates this point. Engineers attempted gold plating to prevent crevice corrosion in an O-ring seal area. After six months in a seawater test loop, the joint leaked. When the flange was removed, the gold plating simply fell out. The “tie-layer” between the piping and gold was active compared to both the piping and gold, and was quickly consumed by galvanic corrosion. The protective coating failed not from seawater attack on the gold, but from galvanic attack on an intermediate layer that the designers overlooked.

For seal materials in seawater service, verify galvanic compatibility before specifying. Premium materials provide no benefit if they create galvanic couples with other assembly components. Request material certifications for all components and verify their galvanic series positions are compatible.

Design Considerations: The Area Ratio Rule

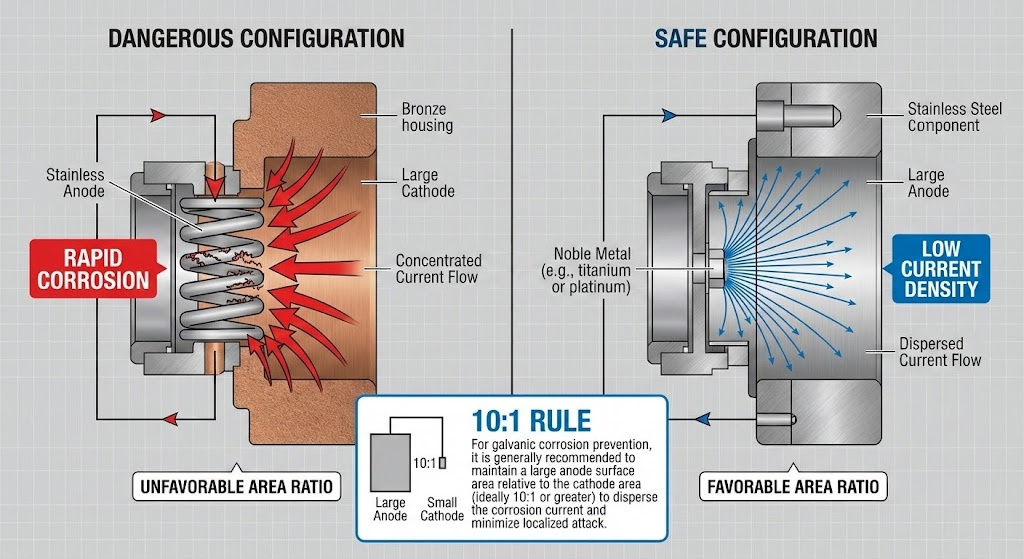

Apply the 10:1 area ratio rule when designing seal assemblies for seawater service. According to ASSDA, if the wetted area of the corroding metal is 10 times the wetted area of the noble metal, galvanic effects are not serious – the larger the ratio, the less severe the galvanic attack.

The ASSDA (Australian Stainless Steel Development Association) explains the principle: due to the electroneutrality requirement in corrosion reactions, the total anodic current must equal the total cathodic current. When a large anode area supplies current to a small cathode, the current density on the anode stays low. When a small anode supplies current to a large cathode, the current density concentrates on the small anode, driving rapid localized attack.

Consider the rivet-plate analogy. An aluminum rivet (small anode) in a stainless steel plate (large cathode) creates an unfavorable ratio – the rivet corrodes rapidly because all the galvanic current concentrates on its small surface area. Reverse the situation with a stainless rivet in an aluminum plate, and corrosion proceeds slowly because the large anode area distributes the galvanic current across many square inches.

In seal assemblies, springs represent a common area ratio problem. A small stainless spring in contact with a large bronze housing will corrode in months. I’ve seen this failure pattern dozens of times in retrofit applications where engineers replaced only the seal faces without considering spring compatibility. The spring wire diameter decreases until it can no longer provide closing force, and the seal fails.

For metal bellows seals, the bellows material selection becomes critical. The bellows presents significant surface area in constant contact with seawater. Hastelloy C-276 bellows offer a solution – galvanic coupling of this alloy to steel or stainless steel does not increase the corrosion on any element of the couple. The alloy’s position on the galvanic series and its inherent corrosion resistance make it nearly neutral in seawater couples.

Hardware sizing follows the same principle. Specify larger fasteners and springs when they must contact more noble materials. The additional surface area reduces current density on the less noble component, extending service life. A spring with 20% more wire diameter can double the time before galvanic attack causes failure.

When complete galvanic isolation isn’t possible, design the assembly so the sacrificial component is inexpensive and easily replaced. A sacrificial anode approach can protect critical seal components if implemented correctly – but this requires deliberate engineering, not accidental galvanic couples from mixed materials.

Installation and Assembly Practices

Eliminate galvanic couples during assembly through material selection and isolation techniques. The most common installation mistake I encounter is using graphite-containing gaskets with stainless steel flanges in seawater service.

Graphite should never contact stainless in seawater. Reports from North Sea platform operations documented problems with graphite-containing gaskets on super duplex stainless steel flanges. The graphite acted as a noble cathode, driving crevice corrosion of the flange face in contact with the gasket. The problems were solved by re-machining the flange faces and changing to neoprene gaskets.

Similar failures occurred on multiple North Sea platforms with super duplex stainless steel – solved by changing to synthetic fiber gaskets. Industry guidance now recommends that graphite in any form should not be used in contact with stainless steels in brackish or seawater. This prohibition applies to gaskets, packing, and even thread lubricants containing graphite particles.

For seal installations, avoid graphite packing or gaskets in the gland area. Specify PTFE, synthetic fiber, or elastomeric gaskets instead. The slight cost premium for non-graphite materials pays back many times over in extended seal life.

O-ring grooves present another galvanic risk. As corrosion experts warn: “Even 316 alloy will, if unprotected, start corroding under soft washers, in O-ring grooves, or any other tight crevice area in as little as one day.” The crevice geometry concentrates corrosion products and creates oxygen-depleted zones that shift the local galvanic potential. O-rings must seal completely to prevent seawater from pooling in the groove.

When installing seals, apply these practices:

Clean all mating surfaces to remove scale, rust, and debris that could create additional galvanic cells. Use stainless steel brushes on stainless components – carbon steel brushes leave particles that become anodes. Even small iron particles from a carbon steel brush can initiate galvanic pitting.

Use compatible thread sealant – some thread compounds contain graphite or metallic particles that create galvanic couples in the thread engagement area. Specify PTFE tape or paste sealants without metallic fillers.

Verify elastomer selection – elastomers don’t participate in galvanic reactions, but they must resist seawater degradation to maintain the seal and prevent electrolyte penetration into crevices. Fluoroelastomers (FKM) or EPDM typically perform well in seawater.

Torque hardware evenly to prevent uneven stress that can accelerate crevice corrosion at gasket interfaces. Use a star pattern and torque in stages.

Document the material of every component in the seal assembly. When troubleshooting future failures, this record allows you to identify galvanic couples that might not be obvious from visual inspection.

Operational Factors and Maintenance

Monitor for galvanic attack signs during routine maintenance – early detection prevents the escalating costs of unplanned downtime. The characteristic indicators differ from general corrosion: look for localized pitting at material junctions, preferential attack on one component while adjacent parts remain intact, and unusual wear patterns on seal faces that suggest binder attack.

Flush the seawater system with fresh water after operation when practical. As one experienced technician noted: “The best way to stop it is to pump a few gallons of fresh water through the raw water system before storage.” Fresh water dilutes the electrolyte, dramatically reducing galvanic corrosion rates during idle periods. This simple practice can extend component life significantly in intermittent-service pumps.

Temperature influences galvanic corrosion rate. Higher temperatures accelerate the electrochemical reactions driving galvanic attack. For pumps operating above 40C (104F), galvanic corrosion concerns compound with chloride stress corrosion cracking (SCC) risks. According to the SSINA, chloride SCC is rare below 60C (140F) in fully immersed stainless steel – but galvanic corrosion accelerates continuously with temperature regardless of this threshold. This distinction matters: your galvanic prevention strategy must address conditions where SCC isn’t yet a factor.

During seal inspections, check these galvanic damage indicators:

Shaft sleeves and holders – Look for localized pitting at contact points with springs, retaining rings, or different-material components. Galvanic attack creates distinctive deep, narrow pits rather than general surface roughening.

Seal faces – On tungsten carbide faces, examine for preferential binder attack that leaves the carbide grains standing proud. This creates a rough surface that accelerates opposing face wear. The face may appear intact to casual inspection but feel rough to touch.

Springs and hardware – Check for diameter reduction or elongation indicating material loss from galvanic attack. Measure spring free length against specification – a shortened spring has lost material.

Gland area – Inspect for crevice corrosion in O-ring grooves and gasket contact surfaces. Run a pick through the groove to feel for pitting that isn’t visible.

An Oceaneering reliability study on 40 production pumps at a North Sea facility identified 12 root causes for recurring seal failures. The operational improvements included standardizing seal installation methods, ensuring pumps operated closer to their best efficiency point, and preventing contamination during maintenance. Implementation of recommendations led to noticeable improvement in pump operational availability through reduced unplanned downtime.

Before replacing the seal, check the shaft and holder for galvanic pitting – this diagnostic step reinforces the thesis that material combinations, not just material quality, drive most failures. Addressing the symptom without fixing the cause wastes money. If you replace a corroded seal with identical materials, you’ll replace it again at the same interval. Identify the galvanic couple and eliminate it through material unification or isolation.

Preventing Galvanic Corrosion: Action Checklist

Material unification prevents more corrosion failures than material upgrade in marine seawater pump seals. The following checklist ensures your seal assemblies avoid galvanic corrosion:

1. Audit material combinations – List every metallic component in the seal assembly (shaft, sleeve, spring, holder, faces, hardware). Verify all metals fall within 0.15V of each other on the galvanic series for seawater.

2. Specify SiC faces for seawater – Silicon carbide with no metallic phase eliminates face-to-holder galvanic cells. If tungsten carbide is required for abrasion resistance, verify the holder material won’t attack the nickel binder.

3. Unify hardware metals – Springs, set screws, and retaining hardware should match the holder and shaft material. Mixed grades of stainless create unnecessary galvanic couples.

4. Eliminate graphite – Replace graphite gaskets and packing with PTFE or synthetic fiber alternatives. Graphite noble cathode behavior accelerates stainless corrosion.

5. Apply the 10:1 rule – When galvanic couples cannot be avoided, ensure the less noble (sacrificial) material has at least 10 times the wetted area of the noble material.

As one experienced practitioner observed: “Based on practical experience, stainless steel can and does hook up with anything in seawater. It might take a little longer to start, but it will.”

The cost of prevention is trivial compared to failure consequences. Industry data indicates that repairing coatings offshore can cost up to 100 times the initial coating cost. Seal failures carry similar multipliers when accounting for production losses, emergency mobilization, and equipment damage.

Your next step: review your current seal specifications and identify any galvanic couples in the assembly. For new installations, request material certifications for all components and verify galvanic compatibility before assembly. When failures occur, document material combinations to identify patterns – the root cause is often galvanic, even when the damage looks like general corrosion.