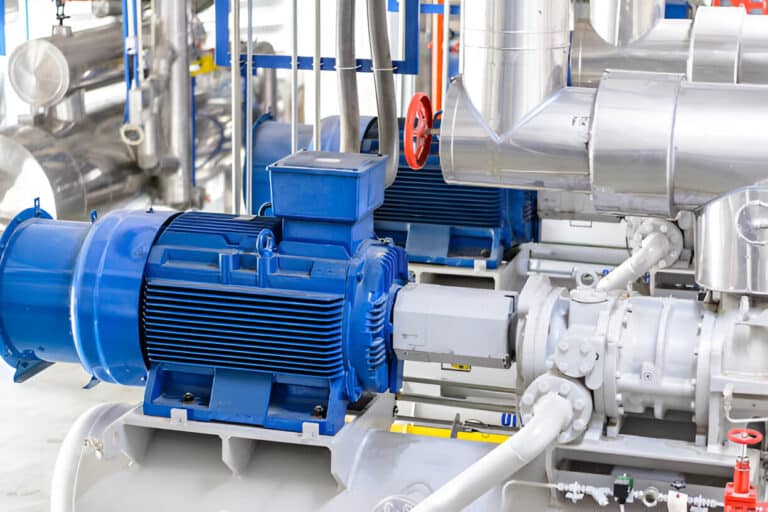

After rebuilding hundreds of failed seals across water treatment facilities, I’ve learned that most selection guides focus on the wrong thing first. Engineers obsess over seal specifications while overlooking a factor that causes more failures than wrong seal selection.

According to John Crane field data, 59% of seal outages at sites using untreated water were caused by water quality issues. Not wrong materials. Not incorrect sizing. Water quality.

This guide covers the complete selection process for water treatment applications – starting with the hidden factor, then moving through materials, configuration, flush plans, and application-specific guidance. By the end, you’ll have a practical framework for selecting seals that actually last.

Water Quality – The Hidden Selection Factor Most Engineers Miss

That 59% statistic deserves explanation. Seal faces operate with a gap of approximately one micron between them. Any contamination in that microscopic space causes damage.

Four mechanisms drive water quality failures:

Abrasive wear from particles. Particles larger than 50 microns damage seal faces on contact. Particles in the 3-50 micron range cause the most insidious damage because they’re small enough to enter the seal interface but large enough to abrade the faces. Below 3 microns, particles pass through without causing significant wear.

Scaling from dissolved minerals. Water vaporizes across seal faces due to the pressure differential. When hard water (above 10 dH) vaporizes, minerals precipitate directly onto the faces. This creates “three-body abrasive wear” where deposits grind between rotating and stationary surfaces.

Blockage leading to dry running. Poor filtration leads to piping blockage. Without adequate flush flow, seals run dry. Under the right conditions, mechanical seals can experience thermal shock and shatter within 30 seconds.

Corrosion from pH extremes. pH levels outside the 6-8 range attack metallic seal components. Chlorides above 50 ppm cause pitting corrosion, particularly at temperatures above 50-55C.

John Crane specifies these limits for seal flush water:

| Parameter | Limit | Failure Mode |

|---|---|---|

| Solids content | <10 mg/l | Abrasive wear |

| Silicate content | <10 mg/l | Abrasive wear |

| Iron content | <1 mg/l | Deposit formation |

| Water hardness | <10 dH | Scaling |

| pH | 6-8 | Corrosion |

| Chlorides | <50 ppm | Pitting corrosion |

The filtration gap is striking. ANSI/HI Rotodynamic Slurry Standard requires 60-micron filtration. Best practice calls for 1-micron filtration – a 60x improvement over the minimum.

Before you specify a new seal, get a water analysis. I’ve seen facilities spend thousands on premium seals only to destroy them with the same contaminated flush water.

Material Selection for Water Treatment Applications

Temperature is the primary driver for seal material selection in water applications. Get this wrong and nothing else matters.

Below 70C (158F): Both EPDM and FKM elastomers work reliably. EPDM handles steam and hot water better, but FKM resists a broader range of chemicals. For standard water treatment, either performs adequately.

Above 70C (158F): This threshold is critical. Fluoroelastomers (FKM/Viton) are not recommended for water applications above 70C. The degradation is severe – I’ve seen 80% of seals fail within 9 months when engineers ignored this limit. EPDM is your only rubber elastomer option above this temperature.

Above 100C (212F): Rubber elastomers don’t survive. Move to graphite or PTFE-based designs with appropriate high temperature seal selection.

Face material selection depends on your water type:

Clean potable water: Carbon against ceramic works well and costs less. This combination handles clean service without over-specification.

High calcium or scaling water: Carbon against silicon carbide outperforms hard/hard combinations. Counter-intuitively, the softer carbon face performs better because it “runs in” after suffering abrasion damage. As one experienced practitioner noted: “When using two hard faces with calcium deposits, users have experienced a lot of abrasion failures.” The carbon self-heals; hard faces don’t.

Abrasive particles: Silicon carbide against silicon carbide provides maximum wear resistance, but only if you’ve addressed particle contamination through filtration. Without filtration, even hard faces wear prematurely.

A critical detail for hot water: Check that your carbon face is antimony-bound rather than resin-bound. Resin-bound carbon fails faster in hot water applications.

For 90% of water treatment applications, EPDM elastomers with carbon/SiC faces handle the job reliably. The remaining 10% require special consideration for temperature extremes or unusual chemistry.

Single vs Double Seal Configuration

The decision between single and double mechanical seals comes down to three factors: regulatory requirements, reliability needs, and total cost of ownership.

When single seals work well:

Single seals handle most water treatment applications where minor fugitive emissions are acceptable. They cost less upfront, require simpler support systems, and perform reliably when process water is clean. If your flush water meets quality specifications and pump criticality is moderate, single seals make economic sense.

When double seals are required:

Potable water production typically requires double seals with barrier fluid for NSF 61 compliance. The barrier fluid provides a clean lubrication zone that prevents any process-side contamination from reaching the drinking water. Beyond regulatory requirements, double seals make sense for high-criticality pumps where unplanned downtime causes significant production losses.

Zero-emission requirements also drive double seal selection. Municipal wastewater systems increasingly mandate no visible leakage, which single seals cannot guarantee.

The cost calculation:

Seal failure costs extend far beyond the replacement part. The cost of downtime can be 5-10 times greater than the cost of the failed seal itself. A $1,500 seal failure typically results in $7,500 to $15,000 in total costs when you factor in emergency labor, production losses, and expedited parts.

One practitioner summarized the math: “Cheaper to buy one double seal a year versus replacing single seals quarterly.”

Calculate your break-even point. If you’re replacing single seals more than twice per year per pump, double seals likely pay for themselves through reduced failures and maintenance labor.

However, I see double seals over-specified for clean water applications. If your water quality is good and regulatory requirements don’t mandate dual seals, the additional complexity and cost may not be justified.

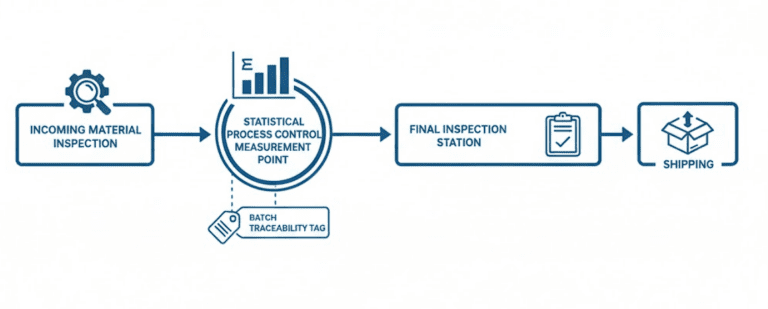

API Flush Plans for Water Treatment

Your API flush plan selection addresses operating conditions – temperature, contamination, and reliability requirements.

Plan 11 – Internal Recirculation

Process fluid recirculates from the pump discharge through an orifice to the seal chamber, then returns to suction. Use Plan 11 when your process water is clean and cool enough to lubricate the seal faces directly.

This is the simplest and lowest-cost option. It works well for clean water below 70C. The limitation is obvious: if your process water isn’t suitable for seal lubrication, you need external flush.

Plan 32 – External Flush

Clean water from an external source flushes the seal chamber. This is the workhorse for water treatment because it addresses contamination at the source. Pressure must be at least 2 bar (29 PSI) above seal chamber pressure to prevent process fluid from entering the seal chamber.

Plan 32 is most effective when paired with 1-micron filtration on the flush water supply. The external source bypasses whatever contamination issues exist in your process water.

Plan 23 – Thermosyphon Cooling

For hot water applications exceeding 70C, Plan 11 recirculation can’t provide adequate cooling. Plan 23 adds an external cooler to reduce seal chamber temperature through thermosyphon circulation.

This plan addresses temperature, not contamination. If your hot water is also dirty, you may need Plan 32 with a cooler instead.

Plan 54 – External Barrier System

An external system pressurizes the barrier fluid between dual seals. Barrier pressure must remain at least 1.4 bar (20 PSI) above seal chamber pressure. This provides the highest reliability for critical pumps.

Plan 54 represents the maximum investment in seal support. Reserve it for applications where any seal failure causes unacceptable consequences.

Decision logic for most water treatment pumps:

- Is the process water clean and below 70C? Plan 11 is sufficient.

- Is the process water contaminated or otherwise unsuitable? Plan 32 with external clean water.

- Is temperature above 70C? Add cooling – either Plan 23 or Plan 32 with a cooler.

- Is zero leakage mandatory or criticality extreme? Consider dual seals with Plan 54.

Most water treatment pumps do fine with Plan 11 or Plan 32. Don’t over-engineer the flush system.

Application-Specific Selection Guidance

Different water treatment applications have distinct requirements. The application type narrows your choices; operating conditions confirm them.

Potable Water Production

NSF/ANSI/CAN 61 certification is mandatory in 49 U.S. states for materials contacting drinking water. This requirement alone shapes your seal selection.

Double seals with barrier fluid are preferred because they prevent any process-side contamination from reaching the product water. The barrier fluid itself must also be NSF 61 certified – typically a food-grade mineral oil or synthetic fluid.

Clean flush water is usually available in potable water facilities, simplifying the support system. Temperature is typically moderate.

Wastewater – Raw and Primary Treatment

Abrasive particles are common. Grit, sand, and organic debris create hostile conditions for seal faces. Silicon carbide against silicon carbide provides the best wear resistance, but external flush (Plan 32) is essential to keep particles out of the seal interface.

Expect shorter seal life than clean water applications. Build maintenance schedules around realistic MTBF expectations, not manufacturer claims based on clean service.

RO and Membrane Concentrate

Reverse osmosis concentrate contains high dissolved solids – everything the membrane rejected. Scaling potential is significant because total dissolved solids can exceed 40,000 ppm.

Carbon against silicon carbide handles scaling conditions better than hard/hard face combinations. The carbon “runs in” after scale damage rather than catastrophically failing.

Monitor concentrate temperature. RO systems sometimes operate at elevated temperatures that push elastomer limits.

Boiler Feed Water

Temperature is the primary challenge. Boiler feed pumps frequently operate above 70C, which eliminates FKM as an elastomer option. Use EPDM exclusively.

Plan 23 thermosyphon cooling addresses the heat load. Without cooling, seal faces overheat and fail prematurely. I’ve seen feed pump seals fail within six months when Plan 11 recirculation was insufficient for 180F service.

Cooling Tower Water

Biological fouling and elevated chlorides create corrosion risk. Cooling tower treatment programs add biocides and scale inhibitors that may affect seal material compatibility.

Monitor pH and chloride levels against the water quality table. Chlorides above 50 ppm with temperatures above 50C accelerate pitting corrosion of stainless steel components.

Selection Checklist and Implementation

Before you start specifying seals, work through this sequence. Skipping steps leads to repeat failures.

Step 1: Identify your application type. Potable, wastewater, RO concentrate, boiler feed, or cooling tower? The application type establishes baseline requirements and narrows material options.

Step 2: Gather operating conditions.

- Temperature: Critical for elastomer selection. Is it above or below 70C?

- Pressure: Determines balance ratio requirements. High-pressure applications need balanced seals.

- Speed: Affects heat generation at the seal faces. High-speed applications may need enhanced cooling.

Step 3: Assess water quality. Get a laboratory analysis covering:

- Particle count and size distribution

- Hardness (dH or ppm as CaCO3)

- pH

- Chlorides

- Iron and silicates

Compare results to the John Crane limits. If parameters exceed specifications, address filtration or use external flush before installing new seals. Otherwise, you’ll destroy the new seals the same way you destroyed the old ones.

Step 4: Select materials.

- Elastomer: EPDM for anything above 70C. FKM only below 70C in non-aqueous or cool water service.

- Faces: Carbon/ceramic for clean water. Carbon/SiC for scaling water. SiC/SiC for abrasive service with good filtration.

Step 5: Choose configuration.

- Single seals: Clean water, moderate criticality, budget constraints.

- Double seals: Potable water (NSF 61), zero-emission requirements, high criticality.

Step 6: Specify flush plan.

- Plan 11: Clean, cool process water.

- Plan 32: Contaminated or hot process water.

- Plan 23: Hot water requiring cooling.

- Plan 54: Maximum reliability requirements.

Step 7: Calculate ROI for upgrades. Compare your current failure rate and costs against projected improvements.

- Current annual failure cost = (failures per year) x (seal cost + downtime cost + labor)

- Upgrade investment = new seal cost + support system changes

- Payback period = investment / annual savings

If you skip water testing, you’ll be back in a week replacing another failed seal. Every experienced field engineer has seen facilities repeat this cycle.

Conclusion

Mechanical seal selection for water treatment requires attention to several factors: materials matched to temperature, configuration matched to criticality, flush plans matched to operating conditions, and application-specific requirements.

But the hidden factor remains water quality. That 59% statistic represents thousands of premature failures that better seal specifications wouldn’t have prevented. Start with a water analysis. Address filtration and flush water quality. Then work through the selection checklist.

Temperature determines your elastomer. Water type determines your faces. Criticality determines your configuration. And water quality determines whether any of it matters.