Your pump suddenly lost suction. The operator noticed the temperature spike and quickly shut everything down. After an hour of cooling, you check the seal again and—the leaking stops. Your heart skips a beat. Did the seal actually fix itself?

I’m here to give you the honest answer: no, it didn’t.

This is the biggest misconception in pump maintenance. Many plant operators and maintenance staff desperately want to believe that a mechanical seal can reseal itself after running dry, especially when it temporarily appears to hold the fluid after cooling down. But what you’re seeing is an illusion—a temporary contraction of materials that masks permanent, microscopic damage beneath the surface.

What Happens to a Mechanical Seal When It Runs Dry?

The Lubrication Film: The Heart of Mechanical Seal Operation

To understand why seals fail when running dry, you first need to understand how they actually work when operating normally.

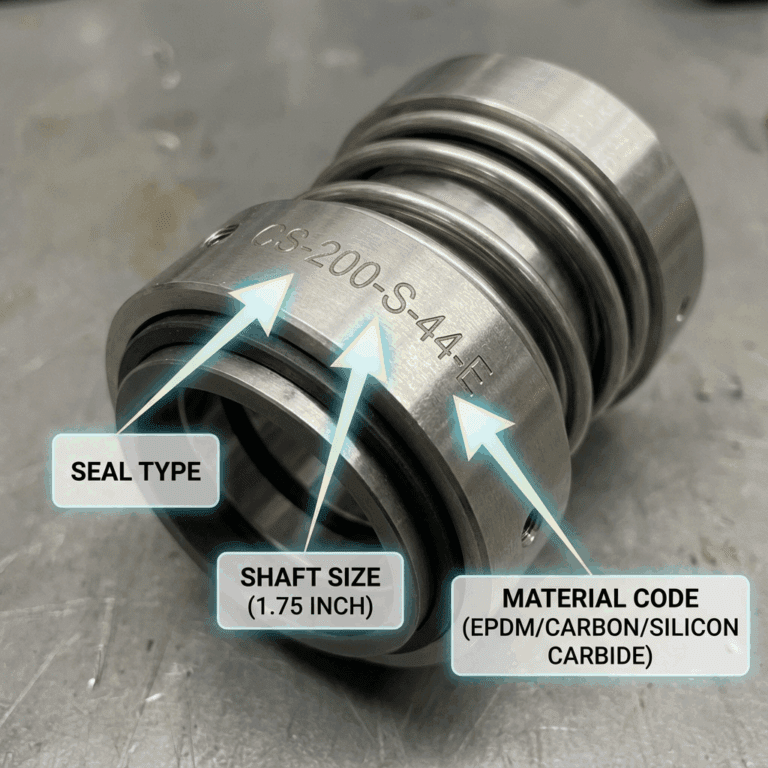

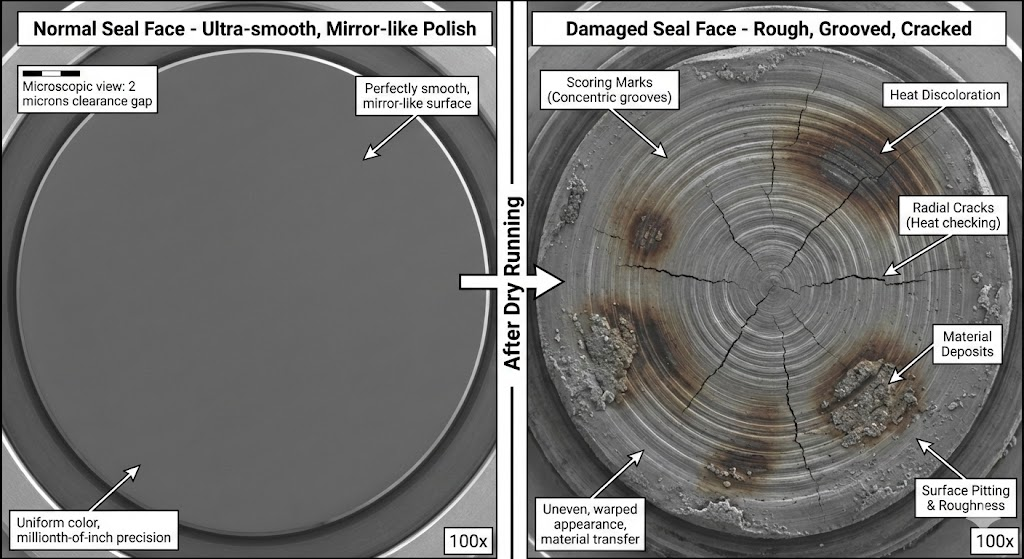

A mechanical seal depends on an ultra-thin film of liquid sitting between two flat faces—one rotating, one stationary. This film is incredibly thin: approximately 2 microns thick. To put that in perspective, a human hair is about 75 microns thick, so this fluid layer is roughly 1/35th the width of a hair.

When everything is working, this balance is perfect. The seal operates with minimal friction, stays cool, and can run for months or years without leaking.

The Moment Lubrication Disappears

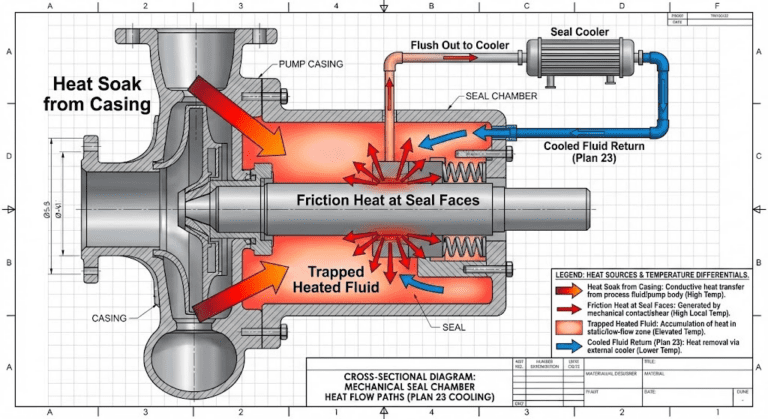

Now imagine that suction line drops below the pump inlet. The fluid level in your suction source is gone. Your pump is running, and the seal is running completely dry—there’s no more lubrication film. Here’s what happens in those critical first seconds:

In the first 2-3 seconds, the seal faces are moving against each other with no fluid between them. Friction builds instantly. The temperature at the seal chamber begins to climb—rapidly.

By 5-10 seconds, the friction has generated so much heat that the seal faces reach temperatures exceeding 1,000°F (538°C). At this extreme temperature, you’d start seeing visible damage to the seal faces—scoring, pitting, and the beginning of material transfer from one face to the other.

Between 10-30 seconds, the extreme heat causes thermal shock. Hard face materials like silicon carbide or tungsten carbide begin to crack in a radial pattern, like spokes on a wheel radiating from the center outward. Softer materials, like carbon, begin to melt and deposit onto the harder face, creating a rough, uneven surface.

By 30-60 seconds, the damage is severe. The mirror-smooth seal faces that were once flat to within millionths of an inch are now scored, cracked, and warped. Complete seal failure typically occurs within one minute of continuous dry running.

Why a Mechanical Seal Cannot Reseal After Running Dry

Here’s where the dangerous myth takes hold: you shut down the pump, the seal cools down to room temperature, and the leaking stops. For a moment, you think everything’s okay. The seal appears to be holding again.

This temporary recovery is real, but it’s not what you think it is. What’s actually happening is material contraction. When the seal cools from 1,000°F back down to room temperature, all the materials in the seal shrink slightly. This contraction can temporarily close small gaps and make the seal appear to hold fluid again, at least for a brief period.

But here’s the critical point: the damage underneath is still there.

Those grooves, cracks, and rough spots on the seal face haven’t gone anywhere. The microscopic precision required for a proper seal—flatness measured in millionths of an inch—has been destroyed. When you restart the pump and pressure builds again, the seal will fail quickly. The temporary recovery was just a cruel tease.

Conclusion

Mechanical seals cannot reseal themselves after running dry. This is a hard truth, but it’s important to accept it because it fundamentally changes how you approach seal maintenance and prevention.

The damage that occurs during dry running—scoring, cracking, material transfer, and warping—happens at the microscopic level and is permanent. While a seal might temporarily appear to recover after cooling, the underlying damage is still there. The precision flatness required for sealing has been destroyed and cannot be recovered without seal replacement.