Emission limits for mechanical seals have tightened sharply over the past 50 years. During the 1970s and 1980s, regulations allowed 10,000 ppm for volatile hazardous air pollutants. That threshold dropped to 1,000 ppm in the 1990s. Current EPA standards set the limit at 500 ppm as measured by Method 21, and some local regulations push as low as 50 ppm.

Each of these thresholds requires a different sealing solution. A single seal that met requirements in 1985 may now trigger compliance violations. This guide provides a selection framework connecting seal arrangements and piping plans to specific emission control requirements.

What Are Fugitive Emissions from Mechanical Seals?

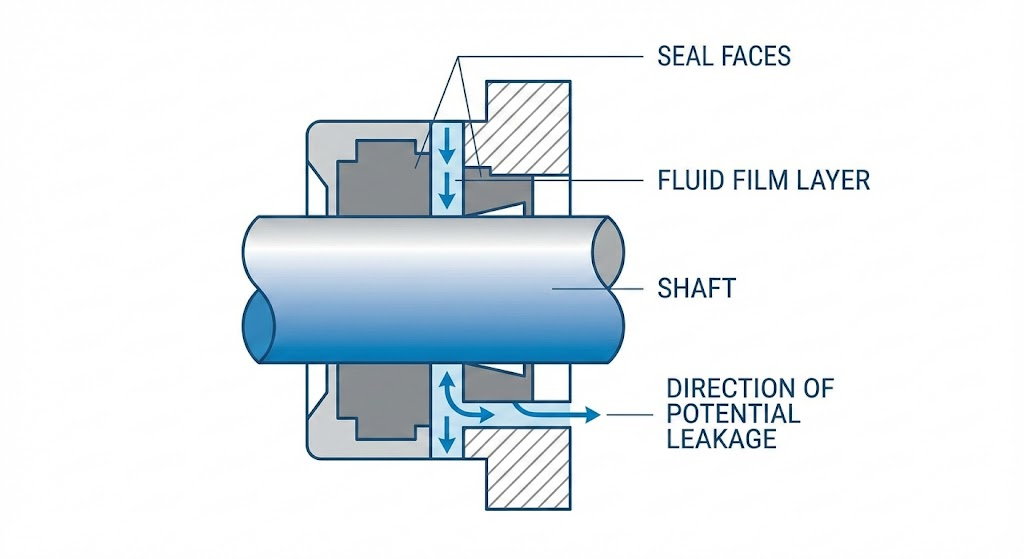

Fugitive emissions are unintended releases of gases or vapors from equipment during normal operation. In pumps and compressors, mechanical seals are common emission points because they must allow a thin fluid film between seal faces for lubrication and cooling.

This is why true zero emissions control is generally not possible with a single seal. All seals depend on fluid migration between the seal faces to function. A double mechanical seal adds a secondary line of defense, but the fundamental physics remain the same at the primary seal interface.

Regulatory thresholds determine which seal configuration you need:

| Era | Limit | Typical Seal Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1970s-1980s | 10,000 ppm | Single seal acceptable |

| 1990s | 1,000 ppm | Low-emission single seal |

| Current EPA | 500 ppm | Dual seal often required |

| Strict local | 50 ppm | Dual pressurized seal |

For compressors and closed vent systems, the EPA leak definition is already 500 ppm. For other equipment including pumps, the general threshold is 10,000 ppm, but most facilities operate under stricter state or consent decree requirements.

The most common mistake I see is engineers specifying seals based on what worked last time rather than checking current local requirements. Regulations vary by state, by facility permit, and sometimes by individual consent decree. Before you start any seal selection, get the actual ppm limit that applies to your installation.

How Seal Arrangements Affect Emission Control

API 682 defines three standard seal arrangements. Each provides different emission control capability.

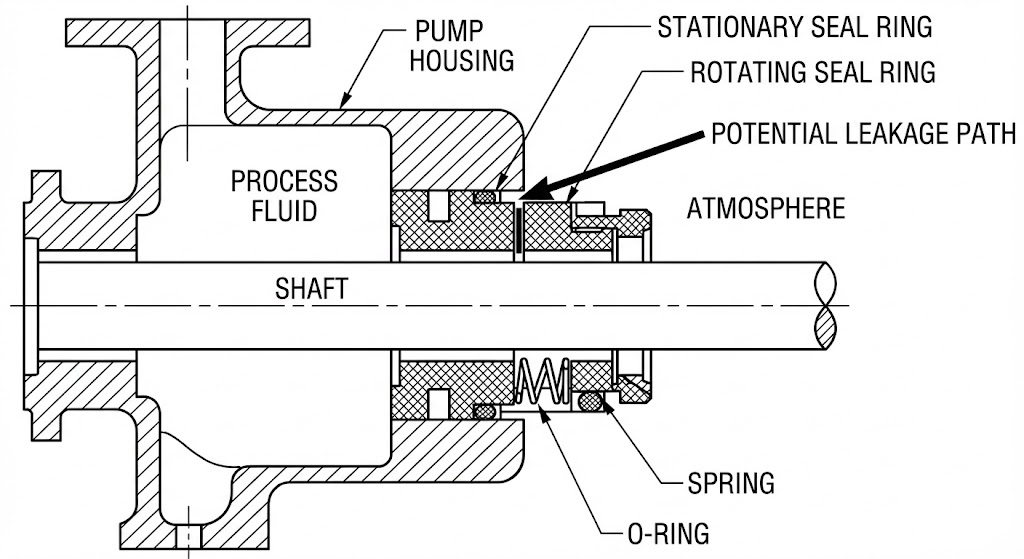

Arrangement 1 (Single Seal)

A single seal can limit emissions to a few hundred ppm with proper design and face materials. This meets the 10,000 ppm threshold for general equipment but falls short of stricter requirements.

Single seals also pose the risk of high emissions from seal failure because they lack a secondary containment barrier. If the seal fails, process fluid leaks directly to atmosphere.

Typical leak rates for single seals run 10-50 milliliters per hour under normal conditions. For non-hazardous fluids with low vapor pressure, this is often acceptable.

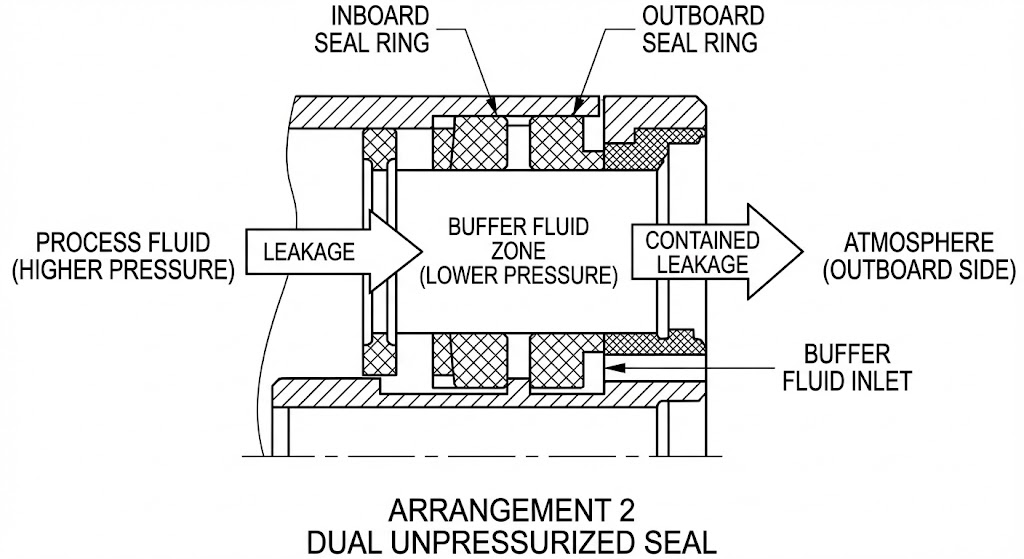

Arrangement 2 (Dual Unpressurized)

Dual unpressurized seals, also called tandem seals, provide a buffer zone between the primary seal and atmosphere. Testing has proven these seals can achieve emissions control below 50 ppm.

The buffer fluid operates at lower pressure than the process. Any primary seal leakage enters the buffer zone rather than escaping to atmosphere. A containment seal on the atmospheric side provides the final barrier.

This arrangement handles most emission requirements below the 500 ppm threshold. I recommend Arrangement 2 as the first consideration for any application requiring better than single-seal performance, unless zero emissions is mandated.

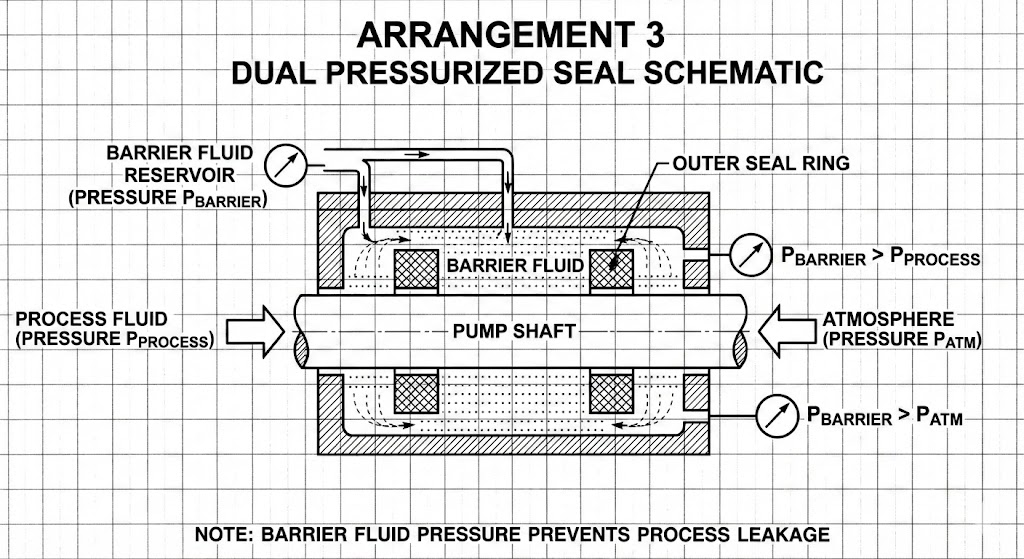

Arrangement 3 (Dual Pressurized)

Arrangement 3 seals close the emissions gap left by dual unpressurized seals. The barrier fluid between the seals is maintained at a pressure higher than the seal chamber pressure.

Both the inner and outer seals are sealing the barrier fluid, not the process. No process leakage migrates to atmosphere because the pressure differential pushes barrier fluid inward, not outward.

This is the only arrangement that provides true zero atmospheric emissions. The trade-off is increased complexity and the requirement for a pressurized barrier system.

| Arrangement | Emission Capability | Complexity | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Single) | Few hundred ppm | Low | Low |

| 2 (Dual Unpressurized) | <50 ppm | Medium | Medium |

| 3 (Dual Pressurized) | Zero to atmosphere | High | High |

Piping Plan Selection for Emission Control

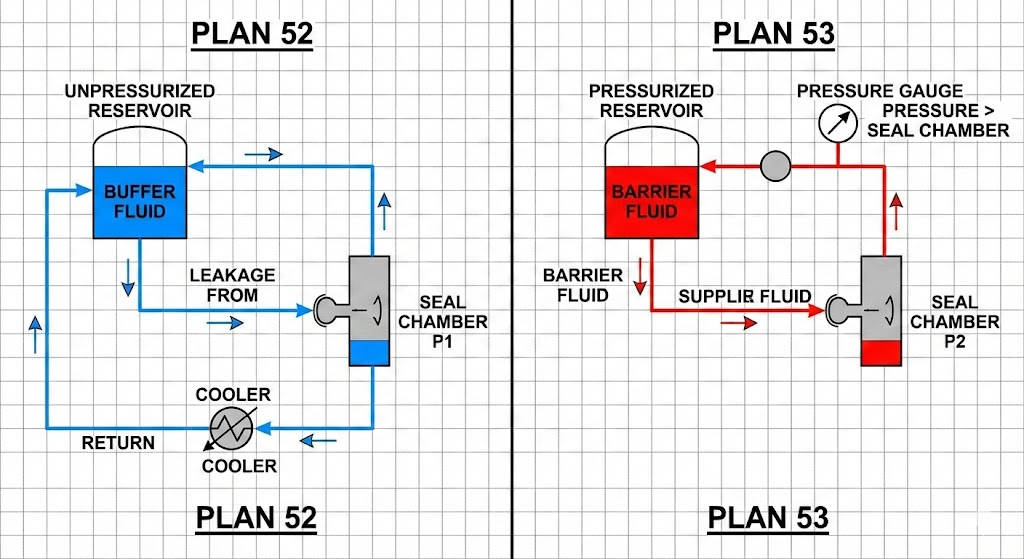

The seal arrangement determines your emission capability, but the piping plan determines how you implement it. For emission control applications, Plan 52 and Plan 53 are the primary options.

Plan 52 uses unpressurized buffer fluid in a reservoir. It is simple and economical with minimal maintenance requirements. The buffer fluid collects any outward leakage from the primary seal, providing detection and containment. This plan works well for non-hazardous or moderately hazardous fluids where the goal is detection rather than absolute prevention.

Plan 53 maintains barrier fluid at higher pressure than the process. Any leakage flows inward into the pump, not outward to atmosphere. For zero-leakage requirements, Plan 53 is mandatory.

API 682 4th edition requires Plan 52, 53A, 53B, and 53C systems to have sufficient working volume of buffer or barrier fluid for at least 28 days of operation. For Plan 53 systems, the barrier fluid must be pressurized at least 1.5 bar (about 22 psi) greater than seal chamber pressure.

The default reservoir capacity specified by API 682 is three gallons for pump shafts smaller than 2.5 inches, five gallons for larger shafts. If you skip this step, you will be back troubleshooting fluid consumption problems within a month.

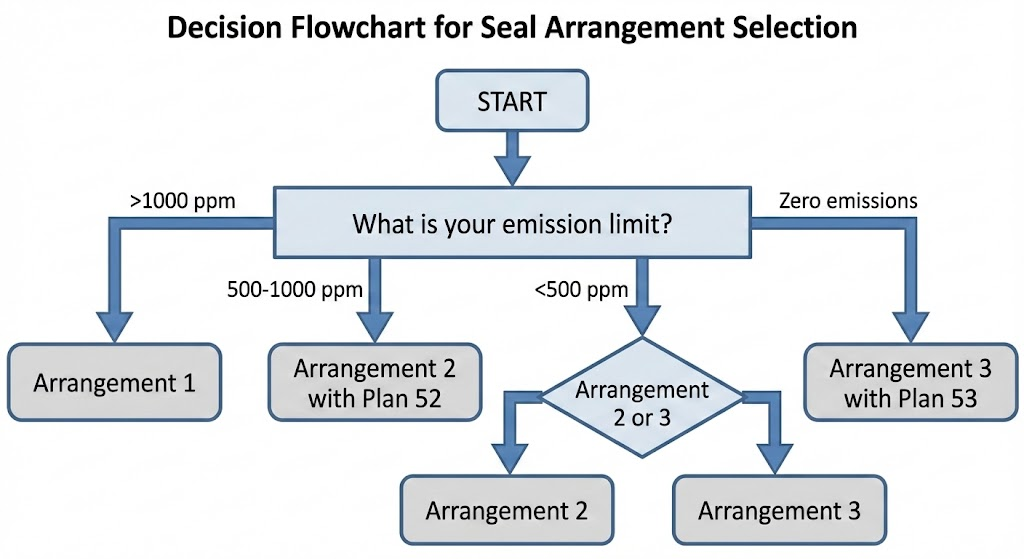

How to Choose the Right Seal for Your Emission Requirements

Start with two questions: What is your regulatory emission threshold? What is the hazard classification of your process fluid?

New pumps in light liquid service containing 5% VOC by weight AND 5% HAP (Hazardous Air Pollutant) by weight must be equipped with dual cartridge seals per EPA and API requirements. This is not optional.

For applications without mandatory dual seal requirements, match your arrangement to the emission threshold:

| Emission Requirement | Recommended Arrangement | Plan |

|---|---|---|

| >1000 ppm | Arrangement 1 | 11, 13, 21, or 23 |

| 500-1000 ppm | Arrangement 2 | 52 |

| <500 ppm | Arrangement 2 or 3 | 52 or 53 |

| Zero emissions | Arrangement 3 | 53A, 53B, or 53C |

There is an ongoing debate about when Arrangement 2 is sufficient versus when Arrangement 3 is required. The practical answer depends on two factors: your regulatory threshold and your fluid hazard class.

For truly hazardous or toxic fluids, or situations under consent decree, only Arrangement 3 provides acceptable protection. For moderately hazardous fluids where the regulatory threshold is achievable with <50 ppm performance, Arrangement 2 is typically sufficient and much less complex to maintain.

A northeast U.S. oil refinery demonstrated this approach on their Hydrofluoric Acid Alkylation Unit. Their original single-cartridge seals with Plan 32 external flush were failing every six months due to inadequate flush supply. They upgraded to dual unpressurized gas buffer tandem seals (API 682 Category II) with proper flush infrastructure. Mean time between repair increased from 6 months to over 1 year, and emissions stayed well below mandated levels.

The upgrade did not require Arrangement 3. Proper execution of Arrangement 2 met their emission requirements at lower cost and complexity. Before you start specifying the most expensive option, verify whether it is actually required for your regulatory threshold and fluid class.

Making the Right Selection

Begin by identifying your actual emission limit, not the assumed one. Check your facility permit, state regulations, and any consent decrees that apply. Then match that threshold to the arrangement capability table above.

When emission control beyond single-seal capability is needed, Arrangement 2 with Plan 52 provides a practical balance of performance, cost, and maintainability. Reserve Arrangement 3 with Plan 53 for applications that genuinely require zero atmospheric emissions or involve highly toxic fluids.

If you have not verified shaft runout before seal installation, the arrangement and plan selection will not matter. A correctly specified emission-control seal installed on a shaft with excessive runout will fail just as quickly as any other seal.