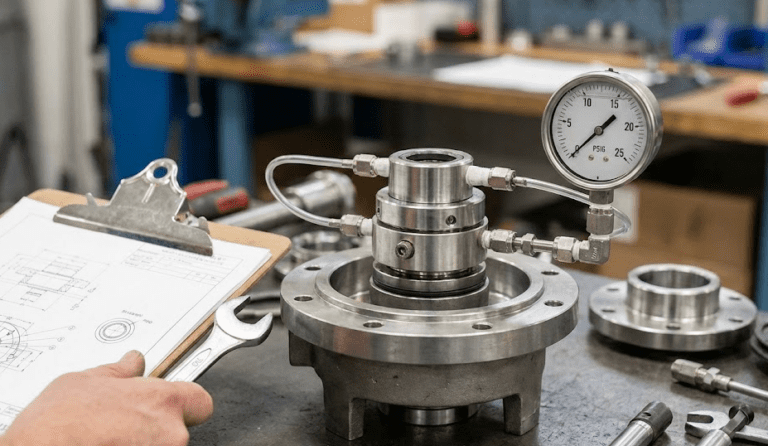

“There is a shocking lack of awareness of the full implications of several pieces of legislation” regarding mechanical seals in food processing. This observation from industry compliance specialists captures a problem I encounter regularly: engineers specifying “FDA-compliant” or “sanitary” seals without understanding which standards actually apply to their application.

Three primary frameworks govern mechanical seals in food and beverage processing: FDA 21 CFR 177.2600 for material safety, 3-A Sanitary Standard 18-03 for design specifications, and EHEDG Guideline 25 for hygienic performance validation. What the spec sheet often fails to communicate is that these standards serve fundamentally different purposes. FDA regulates what materials can contact food. 3-A prescribes how equipment must be designed. EHEDG tests whether designs actually achieve cleanability.

Confusing these distinctions leads to two costly outcomes: over-specification that wastes budget, or compliance gaps that fail audits. This guide examines each standard’s requirements, explains their differences, and provides a framework for selecting the right approach for your application.

FDA 21 CFR 177.2600 Material Requirements

FDA 21 CFR 177.2600 establishes extraction limits for rubber articles intended for repeated food contact. The regulation does not certify seals or approve specific products. It defines maximum extractable matter that materials may release when tested under specific conditions.

The critical detail most specifications overlook: extraction limits differ dramatically based on food type. According to the Code of Federal Regulations, water extraction (for aqueous foods) permits “total extractives not to exceed 20 milligrams per square inch during the first 7 hours of extraction.” Hexane extraction (for fatty foods) permits up to 175 milligrams per square inch under the same test duration.

This ninefold difference in allowable extraction means material selection must match the specific food contact application.

| Test Method | Food Type | Max Extraction (7 hours) | Secondary Limit (next 2 hours) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water at reflux | Aqueous foods | 20 mg/sq inch | 1 mg/sq inch |

| Hexane at reflux | Fatty foods | 175 mg/sq inch | 4 mg/sq inch |

The regulation further categorizes rubber compounds into types (A-D, A-E, A-F) based on their intended food contact applications. Type A-D compounds suit dry foods only. Type A-E compounds are cleared for aqueous and acidic foods. Type A-F compounds handle fatty foods within specific temperature limits.

I’ve seen this specification error dozens of times: engineers write “FDA compliant” on requirements documents without specifying which CFR section, which extraction test, or which food category applies. When that seal contacts a fatty food product, compliance assumptions may prove incorrect.

For mechanical seal materials, FDA compliance verification requires matching the specific elastomer compound to both the food type and the processing temperature. Generic “food grade” claims without CFR references offer insufficient documentation for audit purposes.

3-A Sanitary Standard 18-03 Requirements

3-A Sanitary Standard 18-03 governs mechanical seals, diaphragms, and gaskets used in dairy and food processing equipment. Unlike FDA’s material-focused approach, 3-A prescribes detailed design specifications that equipment must meet exactly.

The standard mandates surface finish of Ra 0.8 um (32 microinch) maximum for all product contact surfaces. Corner radii must be minimum 3 mm for internal angles of 135 degrees or less. Permanent joints require continuous welding, grinding, and polishing to the same surface standard as the base material.

3-A classifies elastomeric materials into temperature categories:

| Category | Maximum Temperature | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Class I | 150C | High-temperature processing |

| Class II | 121C | Steam sterilization |

Testing requirements include milk fat resistance and chemical resistance per defined protocols. Materials must demonstrate no more than 5% volume change when exposed to test media under specified conditions.

The 3-A standard specifies these requirements for a reason: if your design deviates from the specifications, you cannot achieve certification. Period. There is no flexibility for alternative approaches that might achieve equivalent hygiene outcomes.

This prescriptive nature stems from the standard’s history. Before 2003, 3-A Symbol authorization relied on self-certification. Plant inspectors found equipment bearing the 3-A Symbol that did not actually conform to standards. The response was implementing Third Party Verification (TPV) requirements and creating the Certified Conformance Evaluator (CCE) accreditation program. The first CCE exam in 2003 certified 27 individuals qualified to perform conformance evaluations.

Today, USDA relies on 3-A symbol authorization and no longer independently inspects such equipment. The symbol carries regulatory weight because the verification process has teeth.

EHEDG Guideline 25 Classification System

EHEDG Guideline 25 (Design of Mechanical Seals for Hygienic and Aseptic Applications) takes a fundamentally different approach from 3-A. Rather than prescribing exact design specifications, EHEDG establishes performance classes and validates achievement through standardized cleaning tests.

The guideline defines three equipment classes with distinct seal requirements:

Aseptic Class: For sterile products where no microorganism ingress is acceptable. Single mechanical seals cannot meet aseptic requirements. The guideline explicitly requires dual seals with a sterile barrier fluid between the product and atmosphere sides.

Hygienic Equipment Class I: For equipment cleaned in place (CIP) without dismantling. Single mechanical seals are acceptable when properly designed for cleanability. The product-wetted surfaces must be CIP-compatible and the seal must not create dead zones.

Hygienic Equipment Class II: For equipment requiring disassembly for cleaning. Guideline 25 does not cover Class II applications, as the cleaning approach differs fundamentally from CIP-compatible designs.

For equipment to achieve EHEDG certification, the cleanability test must be repeated successfully at least three times. This empirical validation approach means that innovative designs not matching traditional specifications can still achieve certification if they demonstrate actual cleanability performance. EHEDG certificates remain valid for five years.

I’ve seen this specification error dozens of times: engineers specify “hygienic seal” or “EHEDG compatible” without recognizing that single seals fundamentally cannot meet aseptic class requirements. For applications processing sterile products, dual seals with barrier fluid are non-negotiable.

When evaluating elastomer options for mechanical seals, EHEDG certification requires considering both the seal configuration (single vs. dual) and the elastomer’s cleanability characteristics.

3-A vs EHEDG: Prescriptive Specifications vs Performance Testing

The fundamental distinction between 3-A and EHEDG lies in their validation philosophy. While a 3-A certification requires only theoretical review of design requirements against published specifications, EHEDG certification reviews the design both theoretically and practically using standardized hygiene tests.

| Aspect | 3-A Sanitary Standard | EHEDG Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Approach | Prescriptive (design must match specs) | Outcome-based (must pass cleaning test) |

| Validation | Document review against specifications | Physical testing in authorized laboratory |

| Flexibility | None – specifications are mandatory | Permits compensation through demonstrated cleanability |

| If specs not met | Certification impossible | Alternative designs may still qualify if they pass tests |

| Primary market | United States (dairy, food) | Europe (food, pharmaceutical) |

| Certificate validity | Symbol authorization ongoing | 5 years, renewal required |

This difference creates distinct strategic implications. If your seal design cannot precisely match 3-A dimensional specifications, perhaps due to space constraints or legacy equipment adaptation, 3-A certification becomes impossible regardless of actual hygiene performance. EHEDG permits compensatory design elements when cleanability can be proven through standardized testing.

Both standards pursue identical hygiene goals: preventing product contamination and enabling effective cleaning. The difference lies in how they validate achievement of those goals.

For global operations, choose based on your target markets. US dairy and food processing primarily recognize 3-A. European markets expect EHEDG certification. Pharmaceutical applications often require both, plus ASME BPE compliance. For equipment sold globally, dual certification provides the broadest market access.

The comparison between sanitary standards and industrial API mechanical seal standards reveals a similar pattern: each standard serves specific industries and validation approaches.

Material Selection for CIP/SIP Compatibility

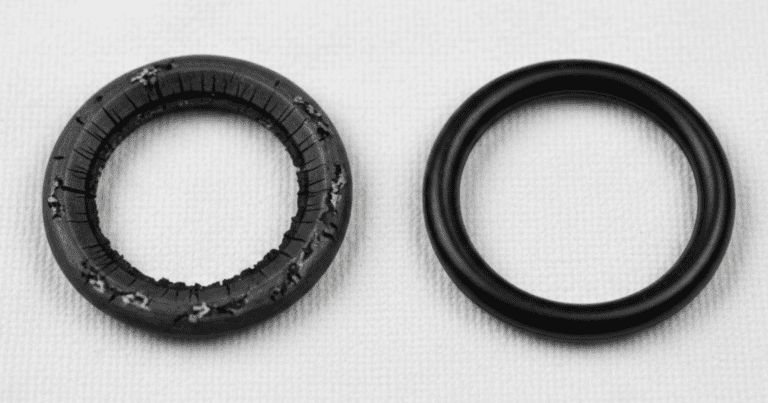

Cleaning-in-place (CIP) and sterilization-in-place (SIP) processes subject seal materials to aggressive chemical and thermal environments. Material selection must match the specific cleaning chemistry, not rely on generic “chemical resistant” claims.

Standard CIP conditions as documented in industry testing protocols:

| Chemical | Concentration | Temperature | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) | 4% | 80C | Protein and fat removal |

| Nitric acid | 2% | 80C | Mineral deposit removal |

| Peracetic acid | 2% | 80C | Disinfection |

SIP steam sterilization requires sustained exposure to saturated steam at 121-134C under 1-3 bar pressure for minimum 20 minutes at the coldest point. FDA CBER 21 CFR 600.11 establishes the 121.5C for 20 minutes time-temperature relationship as the sterilization standard.

Testing of elastomer materials under these conditions reveals significant performance differences:

| Material | CIP Alkaline | CIP Acid | SIP Steam | Max Temp | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFKM | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | 230C | Highest chemical resistance, highest cost |

| EPDM | Excellent | Good | Good | 150C (with O2), 200C (without) | Most cost-effective for typical CIP |

| FKM (Viton) | Weak | Good | Good | 200C | Vulnerable to alkaline attack |

| Silicone | Unsuitable | Unsuitable | Good | 200C | Not recommended for CIP applications |

Claiming FFKM is universally “best” without context wastes significant budget. Premium EPDM handles most CIP regimes at temperatures below 150C with excellent alkaline resistance. FFKM becomes necessary only for aggressive oxidizing chemicals, temperatures above 150C, or applications requiring the absolute broadest chemical compatibility.

For metal bellows mechanical seals, the elastomer selection focuses on secondary sealing elements since the primary seal is metallic. This configuration offers advantages for high-temperature SIP applications where elastomer temperature limits would otherwise constrain operation.

The practical decision: match material to your specific cleaning protocol. If your CIP uses 4% NaOH at 80C followed by 2% acid, EPDM provides excellent service. If your SIP reaches 150C+ steam temperatures, FFKM or metal bellows designs become necessary. Running FFKM in a mild CIP application that EPDM handles perfectly represents unnecessary expense.

Surface Finish and Design Requirements

Both 3-A and EHEDG converge on surface finish requirements despite their different validation approaches. Product contact surfaces must achieve Ra 0.8 um (32 microinch) or better. This consensus reflects decades of research on bacterial adhesion and cleanability.

Surface finish comparison across standards:

| Standard | Designation | Ra Maximum | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-A / EHEDG | Food contact | 0.8 um (32 microinch) | Dairy, food processing |

| USDA | Food contact | 0.8 um (32 microinch) | Meat, poultry processing |

| ASME BPE SF1-SF3 | Mechanically polished | 0.51-0.76 um (20-30 microinch) | Pharmaceutical |

| ASME BPE SF4 | Electropolished | 0.38 um (15 microinch) | High-purity pharmaceutical |

Sanitary mechanical seals typically specify 15-20 Ra microinch (0.38-0.51 um) for seal faces, exceeding the 32 Ra minimum. This enhanced finish improves both sealing performance and cleanability.

Beyond surface finish, hygienic design principles require:

- No dead legs or crevices where product can accumulate and resist cleaning

- Self-draining geometry to prevent pooling

- Continuous welded joints ground and polished to parent material standards

- Radii at internal corners (minimum 3 mm per 3-A) to prevent bacterial harborage

For pharmaceutical applications crossing from food into bioprocessing, ASME BPE surface finish designations become relevant. SF4 electropolished finish at Ra 0.38 um maximum represents the pharmaceutical benchmark, significantly smoother than food-grade requirements.

Regional Standards and Global Compliance

Regional differences in sanitary standards require careful attention for equipment operating across multiple markets or sold internationally.

United States: FDA 21 CFR 177.2600 governs food contact materials. 3-A Sanitary Standards provide the primary design and certification framework for dairy and food processing. USDA requirements align closely with 3-A for meat and poultry processing.

European Union: EC 1935/2004 establishes the framework for food contact materials. A critical gap exists: no EU harmonized standard covers rubber and silicone materials. Member states maintain national provisions, creating a patchwork of requirements. Germany’s BfR recommendations, France’s DGCCRF requirements, and Italy’s ministerial decrees each apply within their jurisdictions. EHEDG guidelines provide voluntary but widely-recognized hygienic design certification.

China: GB 4806.11-2023 establishes requirements for rubber materials in food contact. Testing protocols differ from FDA methods, requiring separate validation for Chinese market access.

Multi-certification becomes the practical path for global operations. Equipment destined for both US and European markets typically requires both 3-A and EHEDG certification. Adding FDA material compliance documentation completes the regulatory package for most applications.

Regional regulations are not equivalent in stringency. A material compound meeting FDA extraction limits may not satisfy BfR requirements. A design certified by 3-A may require modification for EHEDG cleanability testing. Assuming one certification transfers to another market creates audit risk.

Certification vs Compliance: Understanding the Difference

A fundamental distinction that frequently causes confusion: compliance and certification are not synonymous.

Compliance means meeting the technical requirements of a standard. An elastomer compound with extraction values below FDA 21 CFR 177.2600 limits is FDA compliant. A seal design matching 3-A dimensional specifications is 3-A compliant.

Certification means third-party verification and formal recognition of compliance. The 3-A Symbol, EHEDG Certificate, and similar credentials document that an authorized evaluator has confirmed compliance.

The certification landscape varies by standard:

| Standard | Certification Body | Process | Credential |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-A | 3-A SSI with CCE evaluators | TPV inspection of design and manufacturing | 3-A Symbol authorization |

| EHEDG | EHEDG with authorized labs | Physical testing + design review | EHEDG Certificate (5-year validity) |

| FDA | None – self-declaration | Manufacturer maintains compliance data | Compliance statement (no FDA “certification”) |

| EC 1935/2004 | Notified Bodies for specific materials | Varies by material type | Declaration of Conformity |

FDA does not certify products or approve specific seals. Manufacturers self-declare compliance by maintaining test data demonstrating their compounds meet CFR requirements. Claims of “FDA certified” or “FDA approved” mechanical seals misrepresent how the regulatory framework operates.

A seal can be compliant without being certified. A custom seal using FDA-compliant elastomer in a 3-A-compliant design holds no certifications but may fully meet regulatory requirements. Certification provides the audit trail that plant inspectors and quality auditors expect. For new equipment purchases, certification typically represents a procurement requirement rather than a technical option.

Selecting the Right Standards for Your Application

Sanitary seal specifications require matching standards to your specific market, process, and validation requirements. The following decision framework provides a systematic approach:

Step 1: Identify Target Markets

- US only: 3-A certification primary, FDA material compliance required

- EU only: EHEDG certification primary, EC 1935/2004 material compliance required

- Global: Plan for dual 3-A and EHEDG certification

Step 2: Determine Hygiene Class

- CIP without dismantling: EHEDG Class I, single seals acceptable

- Aseptic processing: EHEDG Aseptic, dual seals with sterile barrier mandatory

- Disassembly for cleaning: EHEDG Class II, different design approach

Step 3: Match Materials to Application

- Aqueous foods: Verify FDA water extraction compliance

- Fatty foods: Verify FDA hexane extraction compliance

- CIP chemistry: Select elastomer for specific chemicals and temperatures

- SIP requirements: Verify temperature rating covers sterilization cycle

Step 4: Specify Standards Explicitly

- Reference CFR section (e.g., “FDA 21 CFR 177.2600 Type A-E”)

- State EHEDG class (e.g., “EHEDG Certified to EL Class I”)

- Include 3-A standard number (e.g., “3-A Sanitary Standard 18-03”)

- Avoid vague terms (“food grade,” “hygienic,” “sanitary”)

Step 5: Verify Certification vs Compliance

- Determine if formal certification is required or compliance is sufficient

- Request certification documentation for critical applications

- Maintain material test reports for FDA compliance verification

Sanitary certifications are non-negotiable for food safety. The processing equipment that handles what people eat must meet appropriate standards. Understanding which standards apply, what they require, and how they differ prevents both the waste of over-specification and the risk of compliance gaps.

For applications requiring custom seal solutions or guidance on standard selection, consulting with seal application engineers who understand both the technical requirements and certification processes ensures specifications meet actual operational needs.