A compressor seal is a mechanical device that prevents process gas from escaping where the rotating shaft passes through the stationary compressor casing. It creates a controlled barrier between the high-pressure gas inside the compressor and the external atmosphere.

How Does a Compressor Seal Work?

A compressor seal works by creating a controlled barrier at the point where a spinning shaft meets a stationary housing. The seal faces—one rotating with the shaft, one fixed to the casing—work together to contain pressurized gas while allowing the shaft to spin freely.

Think of it like the seal around a pressure cooker lid, except one part is rotating at thousands of RPM.

The Basic Sealing Principle

Every compressor has a fundamental design challenge. The rotating shaft must pass through the stationary casing to connect with the driver (usually a motor or turbine). This creates a gap that high-pressure process gas desperately wants to escape through.

The pressure differential can be enormous. Some compressors push gas to 500+ bar on the inside while atmospheric pressure sits at just 1 bar on the outside. That’s a pressure difference of 7,000+ psi trying to force its way out.

The seal’s job is to contain that pressure while handling shaft speeds that can exceed 20,000 RPM. Not an easy task.

Step 1: Creating the Seal Interface

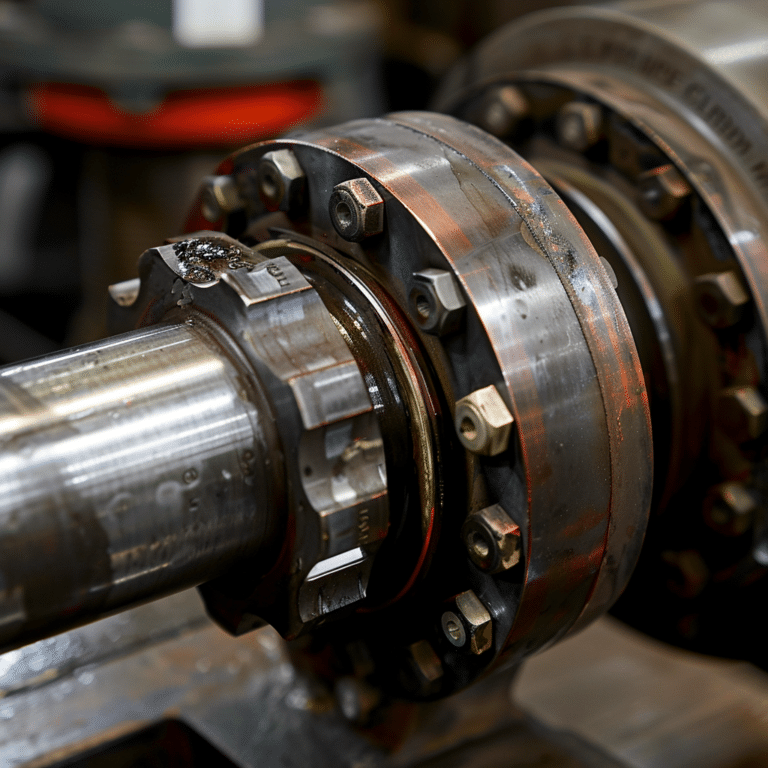

The seal interface consists of two precision-machined faces. The rotating face attaches directly to the compressor shaft and spins with it. The stationary face mounts in a holder fixed to the compressor housing.

Spring force pushes these faces together. In older designs, the faces actually touched and relied on oil or liquid for lubrication. Modern dry gas seals work differently—they maintain a tiny gap between the faces.

The materials matter enormously here. Most seal faces use silicon carbide, tungsten carbide, or carbon graphite. These materials can handle extreme temperatures and pressures while maintaining the flatness required for proper sealing.

Step 2: Managing the Running Gap

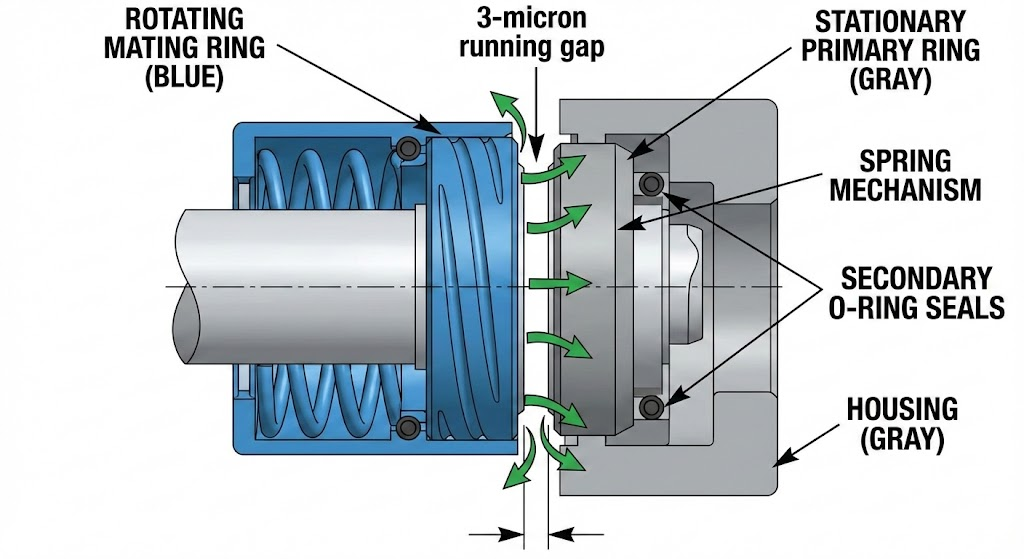

Here’s where dry gas seal technology gets clever. The rotating face has shallow spiral grooves machined into its surface. As the shaft spins, these grooves act like tiny pumps.

Gas gets “scooped up” by the grooves and forced toward the center of the seal face. This creates a hydrodynamic lifting force that separates the two faces by approximately 3 microns—about 1/25th the thickness of a human hair.

This 3-micron gap is the sweet spot. It’s small enough to limit leakage to acceptable levels but large enough to prevent contact between the faces. No contact means no friction, no wear, and significantly longer seal life.

The gap stays stable because the lifting force is self-regulating. If the gap decreases, pressure builds up and pushes the faces apart. If it increases, the pressure drops and springs push them closer together.

Step 3: Controlling Leakage

Even with a 3-micron gap, some gas escapes. This is normal and expected.

The primary vent system captures this leakage and routes it safely—usually to a flare system for hazardous gases or to atmosphere for inert gases. Monitoring the primary vent flow tells you a lot about seal health. A sudden increase often signals developing problems.

Buffer and barrier gas systems add extra protection. Clean, dry nitrogen (or another inert gas) gets injected at higher pressure than the process gas. This creates an outward flow that keeps dirty process gas away from the seal faces.

The seal gas supply is critical. It must be clean (filtered to 3 microns or smaller), dry (at least 20°K above dew point), and at adequate pressure (higher than process pressure). Get any of these wrong, and you’re looking at premature seal failure.

What Are the Main Types of Compressor Seals?

Compressor seals fall into four main categories: dry gas seals, wet seals, labyrinth seals, and carbon ring seals. Each type has specific strengths that make it better suited for particular applications.

Dry Gas Seals

Dry gas seals are non-contacting mechanical face seals that use pressurized gas as the sealing medium. They’ve become the industry standard for centrifugal compressors.

The seal faces separate during operation, riding on a thin gas film just 3 microns thick. This eliminates wear and extends service life dramatically—5 to 10 years is common, with some seals running 15+ years.

Dry gas seals leak 90% less than wet seals. A typical wet seal vents 40-200 cubic feet per minute, while a dry gas seal loses only about 6 cubic feet per minute. That difference translates to massive cost savings and reduced emissions.

The downside? Dry gas seals are highly sensitive to contamination. Dirty gas, liquid droplets, or particles larger than 3 microns can damage the seal faces quickly. They demand clean, conditioned seal gas.

You’ll find dry gas seals on high-speed centrifugal compressors in oil and gas, petrochemical, and power generation applications. About 99% of new centrifugal compressors ship with dry gas seals installed.

Wet Seals (Oil Seals)

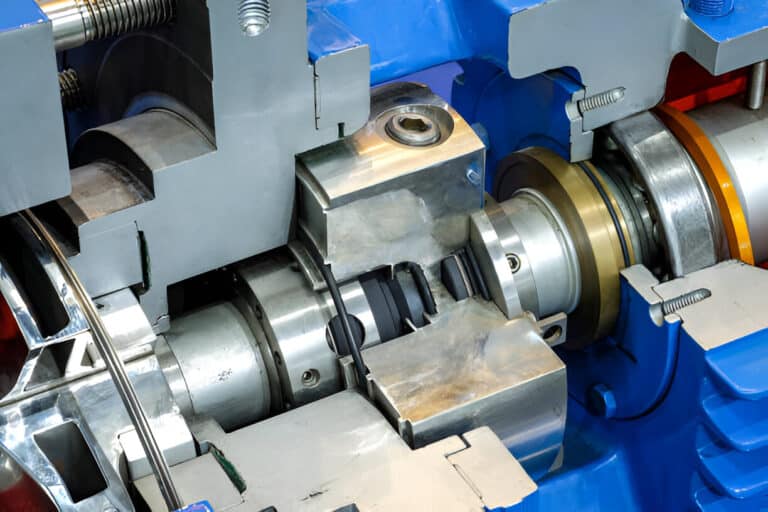

Wet seals use a liquid film—usually oil—to lubricate and cool the seal faces. Oil circulates continuously through the sealing system, creating a barrier between the process gas and atmosphere.

These seals dominated the industry before dry gas technology matured. Many legacy compressors still run wet seals, and some applications genuinely benefit from them.

Wet seals handle contaminated gas streams better than dry gas seals. The oil film can tolerate particles and some liquid without immediate damage. If your process gas is inherently dirty, wet seals might actually be more reliable.

The trade-offs are significant. Wet seals leak 10-30 times more gas than dry seals. The oil system requires pumps, coolers, filters, and constant monitoring. Oil can contaminate your process gas. And service life typically maxes out at 1.5-2 years.

Energy consumption is another factor. Wet seal systems use 50-100 kW of power—roughly 10-20 times what dry gas seal systems consume.

Labyrinth Seals

Labyrinth seals take a completely different approach. Instead of face-to-face sealing, they use a series of interlocking teeth or fins that create a tortuous path for gas to travel.

Each tooth creates a pressure drop. Stack enough teeth together, and you can reduce pressure from high to low gradually. No contact means no wear, and the simple design offers excellent reliability.

The catch is higher leakage. Labyrinth seals can’t match the tightness of face seals. They’re best suited for low-pressure applications or situations where some leakage is acceptable.

You’ll find labyrinth seals on low-pressure air compressors and in applications handling non-hazardous gases. They’re also used as separation seals within dry gas seal assemblies to keep bearing oil away from the main seal.

Carbon Ring Seals

Carbon ring seals split the difference between labyrinth and face seals. Spring-loaded carbon rings contact the rotating shaft, creating a dynamic seal that adjusts to shaft movement.

The carbon material provides natural lubrication and can handle moderate temperatures and pressures. Clearances are smaller than labyrinth seals, resulting in lower leakage.

Carbon ring seals work well for air compressors, nitrogen service, and CO2 applications. They’re simpler and cheaper than dry gas seals while offering better sealing than labyrinths.

The limitation is wear. Carbon rings eventually need replacement as they contact the shaft. They also can’t handle the extreme speeds and pressures that dry gas seals manage.

What Are Common Seal Configurations?

Seal configuration refers to how many seal stages you use and how they’re arranged. The right choice depends on your process hazards, pressure levels, and reliability requirements.

Single Seals

Single seals use one set of seal faces—the simplest and cheapest configuration. One rotating face, one stationary face, one sealing point.

They work fine for moderate-pressure applications handling clean, non-hazardous gases. If the seal fails, you get leakage to atmosphere, but that’s acceptable when the gas isn’t toxic or flammable.

The limitation is obvious. No backup. If the primary seal fails, you’re shutting down.

Tandem Seals

Tandem seals stack two seals in series with buffer gas between them. The primary (inboard) seal handles the process pressure. The secondary (outboard) seal provides backup.

Buffer gas—typically nitrogen at lower pressure than the process—flows between the two stages. This creates a safe intermediate zone and provides redundancy.

If the primary seal degrades, the secondary seal contains any leakage. You can monitor the buffer gas flow to detect problems before they become failures.

Most industrial dry gas seal installations use tandem configurations. The redundancy is worth the extra cost.

Double Seals

Double seals use two seal faces with barrier gas at higher pressure than the process. The barrier gas (usually nitrogen) flows inward toward the process side.

This configuration guarantees zero process gas emissions to atmosphere. Any leakage goes inward, toward the process, not outward.

Double seals are essential for toxic or extremely hazardous gases where any atmospheric release is unacceptable. They’re more complex and require reliable barrier gas supply, but they provide the highest level of containment.