Mechanical seals generate heat. Lots of it. As two precisely machined faces slide against each other thousands of times per minute, friction builds. That heat doesn’t just disappear—it accumulates and damages the seal, shortening its lifespan from years to months or even weeks.

For decades, engineers solved this problem with mechanical pumps. You’d install an external pump, run electricity to power it, maintain it regularly, and hope it didn’t fail at a critical moment. It worked, but it was expensive, complicated, and inefficient.

Then came the thermosyphon system—an elegantly simple solution that harnesses basic physics to solve this exact problem. No pumps. No electricity. No moving parts. Just passive natural convection doing the cooling work while your equipment runs undisturbed.

What Is a Thermosyphon System?

A thermosyphon system is a passive cooling and lubrication system designed specifically for mechanical seals. It circulates cooling fluid without any mechanical pumps, external power sources, or moving parts.

The name itself tells you how it works. “Thermo” refers to heat, and “syphon” refers to the circulation or siphoning action. The system uses heat to create fluid circulation—nothing more.

Unlike pump-driven systems that require electricity and constant maintenance, a thermosyphon system operates through natural convection alone. When your mechanical seal generates heat, that heat enters the cooling fluid. The fluid expands, becomes less dense, and naturally rises upward through piping to a reservoir tank. There, it releases that heat and cools down. The cooled fluid, now denser, flows back down to your seal chamber through gravity alone. This cycle repeats continuously as long as the seal generates heat.

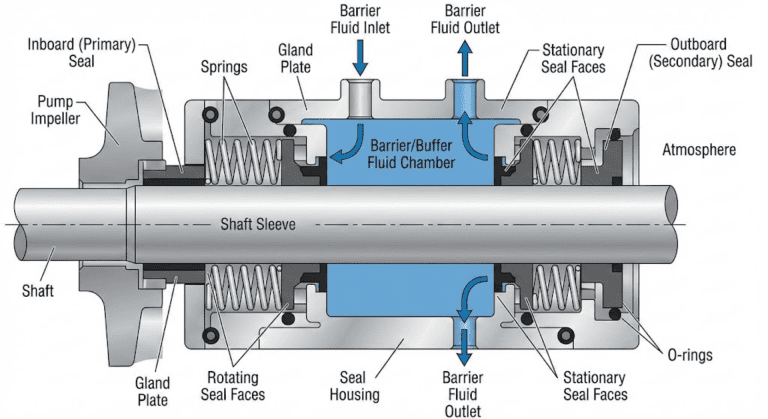

The system accomplishes three critical functions. First, it dissipates the heat generated by seal face friction, preventing thermal damage to seal components. Second, it provides continuous lubrication to prevent the seal from running dry—a condition that destroys seals almost instantly. Third, in double and tandem seal arrangements, it maintains the precise pressure differential required across the seal faces to keep them from separating or leaking.

System Components and Design

A thermosyphon system isn’t complicated. It consists of just five essential components, each playing a specific role in the cooling process.

The Seal Pot (Reservoir Vessel)

The heart of any thermosyphon system is the seal pot—the reservoir tank holding your cooling and lubrication fluid. This isn’t just a storage container. It’s where heat exchange happens.

Most seal pots include sight glasses—transparent tubes letting you visually monitor fluid level. They’re also equipped with fill ports for adding fluid, drain plugs for maintenance, and various connection ports for inlet, outlet, and pressure lines. The top features a pressurization port where you’ll connect your nitrogen gas supply or pressure maintenance system.

Piping and Connections

The piping system is your circulation pathway. Two main lines run between your seal chamber and reservoir: the top line and the bottom line.

The top line carries hot fluid from the seal chamber to the reservoir. This pipe typically has a 1/2-inch to 1-inch diameter depending on the seal system size. The larger the diameter, the lower the flow resistance—which seems good until you realize it also reduces the pressure differential driving circulation. There’s a sweet spot, typically around 3/4-inch diameter, that balances these competing needs.

The bottom line carries cooler fluid from the reservoir back to the seal chamber. It follows the same sizing considerations as the top line.

Heat Exchanger or Cooling Coil

This component is optional, but it’s essential if you’re dealing with significant heat loads or high ambient temperatures.

A thermosyphon system without a cooling coil relies on the seal pot’s walls to dissipate heat to the surrounding air. For light to moderate duty applications in climate-controlled environments, this is fine. The fluid circulates, contacts the cool tank walls, and releases heat to the air.

But add a cooling coil—a finned tube bundle installed inside the seal pot—and you dramatically increase the cooling surface area. Fins extend from the cooling tubes, exposing far more metal to the air. As your circulating fluid flows past this cooling coil, heat transfers efficiently to the coil, then to the surrounding air.

Some systems use water-cooled coils, where cold water from a facility chiller circulates through the coil. Others use air-cooled coils with fans. These options add cost and complexity but give you precise temperature control.

Pressurization System

Your mechanical seal wants to operate under pressure. When the fluid around the seal is pressurized—typically 1–2 bar (15–30 psi) higher than the pump’s operating pressure—the seal faces press together with controlled force. Remove that pressure, and the seal can separate, causing catastrophic leakage.

The pressurization system maintains this required pressure. A nitrogen-charged bladder accumulator is the most common approach. Nitrogen gas on one side of a rubber bladder pushes against your cooling fluid on the other side, maintaining constant pressure.

Temperature Monitoring

This optional but highly recommended component lets you track the condition of your cooling system in real-time.

A simple thermometer well—a small tube inserted into the seal pot—allows you to read the temperature of your circulating fluid with a dial thermometer. Or you can install a temperature sensor connected to your control room, monitoring temperature continuously.

Performance Characteristics and Real-World Capabilities

Heat Dissipation Capacity

The amount of heat a thermosyphon system can dissipate depends on several factors. A standard seal pot without cooling coils can typically handle heat loads up to 5–10 kilowatts, assuming moderate ambient temperature and good installation.

Add a cooling coil, and capacity increases to 15–20 kilowatts. Install water-cooled coils with chilled water supply, and you can handle 25–30 kilowatts or more.

These aren’t hard limits. A well-designed system in a cool environment might exceed these figures. A poorly installed system in a hot facility might fall short. But these figures give you a realistic sense of capacity.

Operating Temperature Ranges

Standard thermosyphon systems operate reliably from 0°C to 150°C. Enhanced systems with cooling coils extend the range to 0–180°C. High-performance systems rated to -60°C to +200°C exist, but they’re specialized and expensive.

Within these ranges, the system performs reliably. Outside these ranges—too cold and the fluid becomes too viscous, too hot and the system’s effectiveness drops—performance degrades.

Pressure Specifications

Most thermosyphon systems operate at pressures between 0–20 bar, with typical operating pressures around 2–10 bar. System pressurization maintains 1–2 bar above the pump’s operating pressure to keep seal faces pressed together.

Relief valves typically open at 2–3 bar above normal operating pressure to protect the system from overpressurization.

Maximum rated pressures for seal pot vessels typically range from 15–40 bar depending on vessel design and wall thickness. But remember—thermosyphon systems aren’t designed to operate at these maximum pressures continuously. They’re designed for moderate pressures.

Reliability and Maintenance

The real advantage of thermosyphon systems shows up in operation. No pumps mean no pump maintenance. No seals in the circulation system mean no circulation seal failures. No control systems mean nothing to troubleshoot or replace.

Properly installed and maintained, a thermosyphon system operates reliably for years with virtually no maintenance beyond occasional fluid level checks and annual fluid changes. This reliability advantage is why thermosyphon systems remain popular despite newer alternatives.

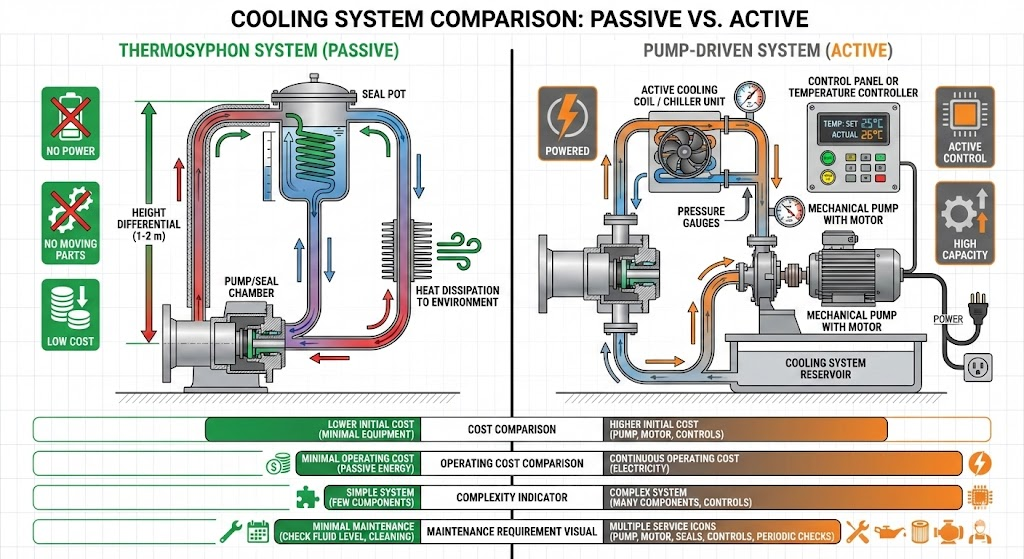

Comparison: Thermosyphon vs. Pump-Driven Cooling Systems

When should you choose thermosyphon? When should you choose a pump-driven system? The answer depends on your priorities.

Thermosyphon Advantages

Cost is the primary advantage. A thermosyphon system costs significantly less than a pump-driven system—often 40–60% less in initial capital investment. Operating cost is nearly zero—no electricity consumption, no pump maintenance, no replacement parts beyond occasional fluid changes.

Simplicity is the second major advantage. A thermosyphon has no moving parts. Nothing to lubricate, nothing to adjust, nothing to replace when it wears out. Installation is straightforward. Operation is passive—plug in and it works.

Reliability flows directly from simplicity. With no external power dependence, a thermosyphon works during power outages. With no pumps to fail or seals to leak, failure points are minimal. For many facilities, this makes thermosyphon systems far more attractive than pump-driven alternatives.

Environmental benefits are real. Zero electricity consumption means zero greenhouse gas emissions from power generation. Passive operation is inherently green technology. No pump waste, no complex controls requiring disposal—just simple, efficient cooling.

Pump-Driven System Advantages

Heat capacity is the primary advantage of pump-driven systems. Active circulation can handle heat loads two to three times higher than passive systems. For high-heat applications, pump-driven is often the only option.

Temperature control precision is the second major advantage. Pump-driven systems with active controls maintain temperature within ±2–5°C. Thermosyphon systems typically maintain ±10–15°C. For temperature-sensitive processes, pump-driven systems are required.

Pressure capacity is higher with pump-driven systems. They can reliably maintain pressures exceeding 40 bar—well beyond thermosyphon capability. For extreme high-pressure applications, pump-driven is necessary.

Flexibility is the final advantage. Pump-driven systems work in any physical orientation. Thermosyphon systems require height differential between reservoir and seal. If your installation space doesn’t allow proper positioning, pump-driven is your only option.

The Reality: It’s Application-Specific

For applications with moderate heat loads, reasonable operating temperatures, and cost sensitivity, thermosyphon wins. You save money, gain reliability, and reduce maintenance.

For applications with high heat loads, tight temperature control, or extreme pressures, pump-driven wins. You gain capability at the cost of complexity and expense.

Many facilities use both. Thermosyphon systems on the smaller, simpler pumps. Pump-driven systems on the critical, high-capacity equipment. This mixed approach balances cost and capability effectively.