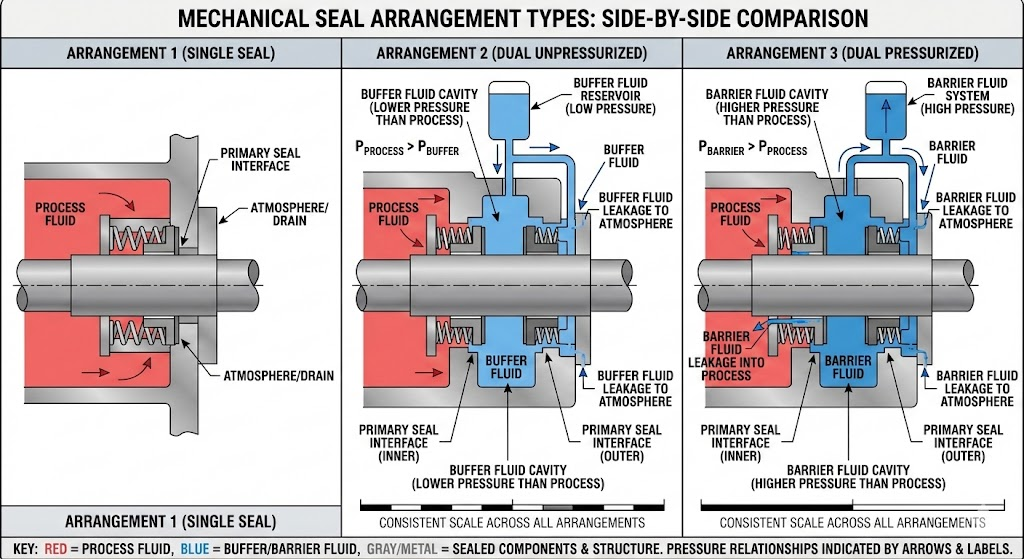

Mechanical seals are classified into three primary arrangements based on how many seals work together and how their supporting fluid gets pressurized. Think of arrangements like different levels of protection—each one solves a different problem.

Why does arrangement matter? Your choice directly impacts whether your pump runs for three years or fails in three months. It determines whether toxic chemicals stay contained or leak into the environment. It affects whether you’re doing maintenance once a year or calling the technician monthly.

Understanding these three arrangements—Arrangement 1 (single seal), Arrangement 2 (dual unpressurized), and Arrangement 3 (dual pressurized)—gives you the knowledge to make decisions that balance safety, reliability, and cost.

Arrangement 1: Single Mechanical Seals — The Workhorse for Standard Applications

How Single Seals Actually Work

A single mechanical seal consists of two main parts: a rotating seal face bolted to your shaft and a stationary seal face mounted on the pump housing. These faces press together with spring force, creating a thin film of liquid between them. That liquid does the real work—it lubricates, cools, and prevents metal-to-metal contact while stopping leakage.

Why Single Seals Win for Basic Jobs

Single seals dominate industrial equipment for good reason. They’re inexpensive—you’re not buying two seals for one application. Installation is straightforward, so your maintenance team won’t need specialized training. Parts are everywhere, so you’re never scrambling for replacement seals.

You also get minimal maintenance headaches. Single seals run quietly, don’t require external fluid circulation systems, and your operators can focus on the equipment rather than monitoring seal support systems.

For handling clean, non-hazardous liquids where a little controlled leakage is acceptable, single seals are your go-to choice. That’s why they’re the most widely used seal arrangement in industrial pumping applications.

The Serious Limitations

Here’s where single seals fall short: they offer zero redundancy. When that seal fails—and it will eventually—process fluid goes straight to atmosphere. For toxic chemicals, flammable liquids, or expensive specialty fluids, this isn’t just an environmental problem. It’s a liability nightmare.

Single seals also can’t handle applications where you absolutely need zero emissions. Modern EPA regulations are getting stricter. If you’re pumping fluids above 1.5 psia vapor pressure, you may face mandatory monitoring or forced compliance upgrades.

The physics matter here too. Single seals depend entirely on the process fluid for lubrication. With poor-lubricating fluids—thick oils, viscous chemicals, or certain solvents—seal face wear accelerates dramatically. Your seal life drops from years to months.

When You Should Use Arrangement 1

Arrangement 1 works perfectly for:

- Water and low-viscosity, non-hazardous liquids

- General industrial pumping where emissions are not a concern

- Applications where you prioritize low cost over redundancy

- Systems where controlled leakage is acceptable

- Equipment where simplicity and minimal maintenance win over complexity

If your biggest concern is cost and your fluid is benign, Arrangement 1 is your answer.

Arrangement 2: Dual Unpressurized Seals — Environmental Protection with Failsafe Redundancy

The Buffer Fluid System Explained

Arrangement 2 flips the script by adding a second seal and introducing a buffer fluid—a safe, clean liquid that circulates between your two seals at a pressure lower than the process fluid.

Here’s what happens: Your inner seal faces the dangerous process fluid, just like a single seal. But if it fails, any leakage doesn’t escape to the atmosphere. Instead, it flows into the cavity between the inner and outer seal. That’s where the buffer fluid catches it.

The outer seal then seals that buffer fluid under much lower pressure. You’ve created a safety net. Even if your inner seal fails completely, the outer seal keeps dangerous chemicals contained until you can schedule maintenance.

The buffer fluid isn’t just a container for leakage. It’s working hard. It flows past the inner seal, cooling the seal faces and providing lubrication that the dangerous process fluid couldn’t offer. For thick, poor-lubricating chemicals, this buffer fluid is crucial—it can triple seal life compared to single seal performance.

Three Physical Configurations You Need to Know

Arrangement 2 comes in three different physical layouts, each suited to different space constraints and operating conditions:

Back-to-Back Configuration: Both rotating seal faces point away from each other. This arrangement needs barrier fluid (pressurized higher than the process fluid) in the cavity between them. Back-to-back seals handle pressure reversals gracefully and maintain reliable lubrication even if pressure fluctuates. They’re the most common Arrangement 2 configuration for general applications.

Tandem (Face-to-Back) Configuration: Both seals face the same direction—one after the other—with buffer fluid flowing between them. Tandem seals shine in critical applications because the outboard seal acts as a true backup. If your inner seal fails, the outer seal takes over immediately. No downtime waiting for repairs. You can schedule maintenance at your convenience.

This redundancy comes at a cost: tandem seals need more space along your shaft. If you’re retrofitting into equipment with tight space constraints, you might hit shaft deflection problems.

Face-to-Face Configuration: The rotating faces share space between stationary faces. This compact arrangement fits where space is tight. It works with pressurized barrier fluid, but it sacrifices cooling efficiency compared to back-to-back or tandem designs. The tradeoff: compactness for thermal management.

Why Arrangement 2 Makes Hazardous Fluids Manageable

Companies pumping toxic chemicals, flammable liquids, carcinogenic substances, or explosive materials almost universally choose Arrangement 2. The redundancy is non-negotiable. One failed seal can’t release hazardous fluid to the environment—the backup seal protects you.

The environmental angle matters too. Captured leakage collects in the buffer cavity where you can access it, dispose of it properly, and even measure how much escaped. No surprises, no violations.

Equipment uptime improves significantly. Your maintenance crew doesn’t need to rush to prevent catastrophic leakage. They can plan repairs during scheduled downtime. The outer seal buys you time.

The Real Costs and Complexity

Arrangement 2 isn’t free. You’re buying two seal assemblies instead of one. Initial equipment cost jumps 50-100% compared to single seals. Installation requires more precision, so labor costs climb.

The infrastructure demands get serious. You need a seal support system: a reservoir to hold buffer fluid, cooling equipment to keep that fluid from overheating, filters to keep contamination out, and instrumentation to monitor pressure. That’s not a pump anymore—it’s a system.

Your operations team needs to maintain this system. Buffer fluid gets contaminated over time. It needs regular monitoring. Standards suggest complete fluid replacement at intervals, though the industry hasn’t standardized exact timings yet. You’re now managing a continuous maintenance task.

If buffer fluid pressure drops below process fluid pressure, the entire safety advantage evaporates. A faulty pressure gauge or failed circulation pump can turn your redundant system into a liability. That’s why monitoring isn’t optional—it’s essential.

Thermal management can challenge you, especially in tandem configurations. The inner seal’s location creates a stagnant zone where buffer fluid doesn’t flow efficiently. Heat builds up. Some applications see significantly reduced seal life unless you engineer cooling carefully.

Where Arrangement 2 Belongs

Deploy Arrangement 2 for:

- Toxic or carcinogenic fluids

- Flammable liquids requiring environmental containment

- Volatile chemicals where zero emissions matter

- Viscous or abrasive fluids that would destroy single seal faces quickly

- Critical equipment where you can’t afford unexpected downtime

- Applications regulated by EPA or similar environmental agencies

If environmental protection or redundancy is non-negotiable, Arrangement 2 is your answer.

Arrangement 3: Dual Pressurized Seals — Maximum Containment for Extreme Hazards

How Barrier Fluid Creates Bulletproof Containment

Arrangement 3 takes safety to another level. Instead of a buffer fluid at lower pressure, you use a barrier fluid maintained at higher pressure than the process fluid. Think of it as a pressure shield.

Both your inner and outer seals now work on this pressurized barrier fluid, not the dangerous process liquid. The process fluid never touches the environmental seal. It never gets a chance to escape.

Here’s the physics that makes it work: Your pressurized barrier fluid creates a positive pressure differential pushing inward from all sides of the inner seal. Even if you had multiple simultaneous failures, pressure alone keeps process fluid contained. It’s not relying on seal face contact anymore—physics is doing the work.

For the inner seal, this pressurized barrier fluid offers superior lubrication. No poor-lubricating process fluid destroying your seal faces. The barrier fluid glides across those faces smoothly, extending seal life significantly compared to single seals.

The Guarantee: Near-Zero Emissions

Here’s the promise Arrangement 3 delivers: near-zero emissions of process fluid to atmosphere. This isn’t marketing talk—it’s physics. Process fluid simply can’t leak out when everything around it is at higher pressure.

This makes Arrangement 3 non-negotiable for carcinogenic chemicals, extremely toxic substances, or expensive proprietary fluids where even tiny leaks matter. Pharmaceutical companies, petrochemical plants, and specialty chemical manufacturers rely on Arrangement 3 when the consequences of failure are severe.

Regulatory compliance becomes straightforward. You’re not monitoring emissions—you’re preventing them. EPA exemptions exist for dual pressurized seals with properly maintained barrier systems. That regulatory relief alone can pay for the system over time.

The Cost of Ultimate Protection

Arrangement 3 represents the peak of complexity. You’re running two seals plus a sophisticated barrier fluid system. Equipment costs run $3,000-$10,000+ just for the seal assembly, then add the support infrastructure.

The barrier system demands constant attention. Pressure must stay higher than process pressure—always. Barrier fluid must stay clean and compatible with both the process fluid and your seal materials. Temperature must stay within limits. Everything must work perfectly.

Skilled personnel become mandatory. This isn’t a system an entry-level technician troubleshoots. You need engineers and experienced seal specialists. Training your maintenance team gets expensive.

System failures can happen at critical moments. If cooling fails, barrier fluid temperature climbs. If pressurization fails, you lose your advantage. If contamination gets into the barrier fluid, seal performance degrades. Each failure point is serious.

Long-term fluid management creates ongoing costs. Barrier fluid degrades. Contamination accumulates. Complete fluid replacement intervals need planning. You’re managing an active system continuously, not just a pump.

When the Highest Protection Pays Off

Arrangement 3 makes sense for:

- Carcinogenic or acutely toxic substances

- Extremely flammable or explosive chemicals

- Expensive specialty fluids where any loss impacts operations

- Food and pharmaceutical production with purity requirements

- Applications where failure consequences are catastrophic

- Regulatory environments with zero-emission mandates

If the cost of any leakage exceeds the cost of the system, Arrangement 3 is justified.

Quick Comparison: Which Arrangement Fits Your Application?

| Factor | Arrangement 1 | Arrangement 2 | Arrangement 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Cost | Lowest ($1-3K) | Moderate ($2-5K) | Highest ($3-10K) |

| Installation Complexity | Simple | Moderate | Complex |

| System Support Required | None | Moderate (reservoir, circulation) | Extensive (pressurization, cooling, monitoring) |

| Redundancy | None | Yes (one seal backup) | Yes (full containment) |

| Environmental Protection | None | Good (captures leakage) | Maximum (near-zero emissions) |

| Typical Seal Life | 18-36 months | 36-60 months | 36-60 months |

| Annual Maintenance Cost | Low | Moderate | High |

| Best For | Non-hazardous fluids, cost priority | Toxic fluids, redundancy needed | Hazardous fluids, zero leakage required |