I’ve seen engineers pick the wrong seal and watch it fail within weeks. Wrong material for the temperature. Wrong configuration for the pressure. Wrong design for the fluid. Each mistake costs money, causes downtime, and creates safety hazards that nobody wants to deal with.

This guide breaks down every major seal type, explains how they work, and tells you exactly when to use each one. You’ll learn to match seals to your specific application instead of guessing.

What Are the Main Types of Mechanical Seals by Arrangement?

Single Mechanical Seals

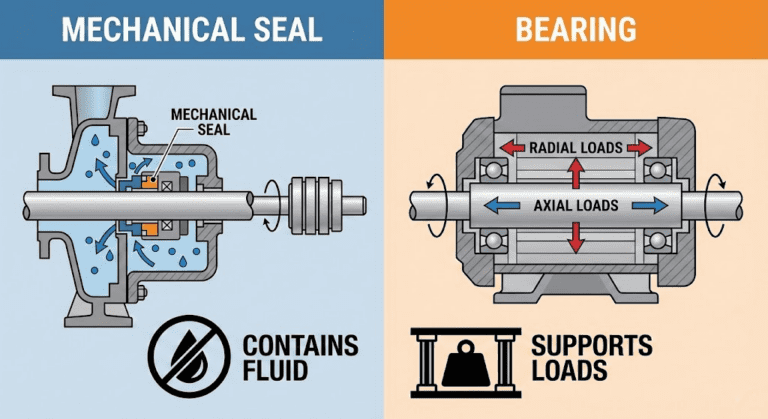

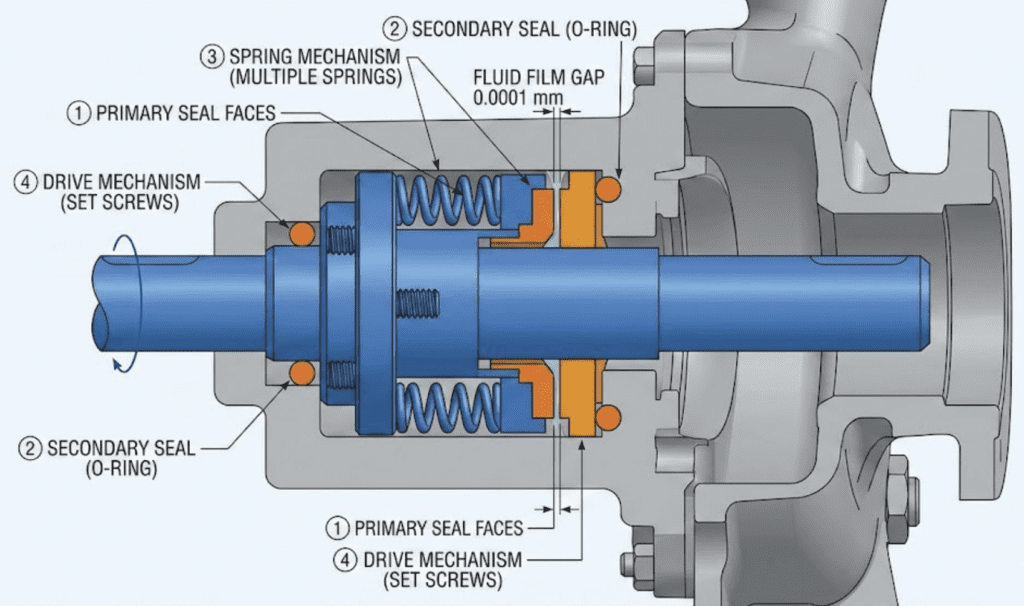

Single seals use one rotating face and one stationary face to create a barrier between the pump interior and the atmosphere. The pumped liquid itself lubricates and cools the seal faces.

This is the workhorse design for most pumping applications. If you’re moving water, light oils, or mild chemicals at reasonable temperatures and pressures, a single seal handles it fine. The design is simple, the cost is low, and replacement is straightforward.

Single seals work best when the pumped fluid has decent lubricity and doesn’t contain abrasive particles. Clean water at ambient temperature? Perfect application. Light hydrocarbons in a refinery utility service? Usually fine. Lubricating oils in a circulation system? No problem.

The limitations are clear: if the seal fails, nothing stops the fluid from escaping. There’s no backup, no redundancy. For water or light oils, that means a mess and some lost product. For toxic or flammable chemicals, it means a serious safety incident.

Single seals also struggle with fluids that flash to vapor at seal face temperatures, fluids loaded with abrasive solids, and fluids with poor lubricity. When process conditions push these boundaries, you need a different solution.

Industries that rely heavily on single seals include water and wastewater treatment, HVAC systems, general manufacturing, and any application where the pumped fluid isn’t hazardous and operating conditions stay moderate.

Double (Dual) Mechanical Seals

Double seals use two complete seal assemblies—an inboard (inner) seal and an outboard (outer) seal—with a barrier or buffer fluid between them. This creates two lines of defense against leakage.

When you’re pumping something that absolutely cannot escape to atmosphere—toxic chemicals, carcinogens, flammable hydrocarbons, or expensive specialty fluids—double seals are often the only acceptable choice.

Two main arrangements exist:

Back-to-back configuration positions both seals facing away from each other, with the barrier fluid between them at higher pressure than the process fluid. The pressurized barrier actively prevents any process fluid from reaching the outer seal. If you need zero emissions, this is the setup.

Tandem configuration arranges both seals facing the same direction, with a buffer fluid between them at lower pressure than the process. The inner seal contains the process fluid normally; the outer seal acts as a backup and contains any leakage that gets past the first seal. This works well when you want containment of minor leakage but can tolerate some buffer fluid mixing with the process.

The barrier fluid system makes double seals more complex. You need a reservoir, circulation system, and pressure control to keep the barrier fluid flowing between the seals. API 682, the industry standard for pump sealing systems, defines several piping plans for these systems:

Plan 52 uses an unpressurized buffer fluid that circulates through natural convection. Simple and inexpensive, but provides no positive barrier against process leakage—just a way to detect and contain minor failures.

Plan 53A pressurizes the barrier fluid using an external gas source (usually nitrogen) in a reservoir. This is the most common approach for double seals handling hazardous fluids. The barrier fluid volume is limited to what’s in the tank, so contamination of the process stays controlled.

Plan 53B and 53C use bladder or piston accumulators to pressurize the barrier fluid. These provide more stable pressure control and can track system pressure changes dynamically.

Plan 54 supplies barrier fluid from an external pressurized source at a controlled flow rate. It handles the highest heat loads and is considered the most reliable double seal system, though it requires the most infrastructure.

When should you upgrade from single to double seals? Regulatory requirements often force the decision—handling listed hazardous materials typically mandates double seals. But even when regulations don’t require it, double seals make sense for expensive process fluids (where any loss hurts the bottom line), fluids with poor lubricity (where the barrier fluid provides better lubrication than the process), and situations where any visible leakage would trigger safety concerns.

What Are Balanced vs. Unbalanced Mechanical Seals?

The difference between balanced and unbalanced seals comes down to how much of the pump’s hydraulic pressure pushes the seal faces together.

| Feature | Balanced Seal | Unbalanced Seal |

|---|---|---|

| Recommended pressure | Above 200 PSIG | Below 200 PSIG |

| Heat generation | Lower | Higher |

| Face wear rate | Slower | Faster |

| Tolerance to poor lubrication | Better | Worse |

| Stability under vibration | Lower | Higher |

| Cost | Higher | Lower |

| Complexity | Higher | Lower |

Balanced Seals

Balanced seals use a stepped or tapered design that reduces the effective pressure acting on the seal faces. Instead of full system pressure pushing the faces together, only a fraction of that force applies to the sealing interface.

This matters enormously for seal life. Lower face loading means less friction, less heat, and slower wear. A balanced seal running at 400 PSIG might generate the same heat as an unbalanced seal at 100 PSIG.

Balanced seals handle challenging fluids better than unbalanced designs. Liquids with low viscosity, low lubricity, or high vapor pressure all benefit from the reduced face loading. The cooler operation keeps the fluid from flashing to vapor between the faces—a common failure mode with volatile liquids.

Most manufacturers recommend balanced seals for applications above 200 PSIG. In practice, I’d consider them for any service with demanding fluids, even at lower pressures. The longer life often justifies the higher initial cost.

High-pressure pumping in refineries, volatile hydrocarbon service, and boiler feed applications typically use balanced seals as standard.

Unbalanced Seals

Unbalanced seals let full hydraulic pressure act on the seal faces. The design is simpler—no stepped sleeve or other balance features needed. This makes them less expensive and easier to manufacture.

The higher face loading creates more friction and heat, which limits unbalanced seals to lower-pressure applications. Push an unbalanced seal too hard and the faces will overheat, destroying the lubricating film and accelerating wear.

But unbalanced seals have a real advantage: stability. The higher face loading makes them more resistant to opening under vibration, shaft deflection, or pressure fluctuations. In applications with rough operating conditions but low pressures, unbalanced seals often outlast their balanced counterparts.

Water pumping, low-pressure chemical service, and general industrial applications commonly use unbalanced seals. They’re the economical choice when operating conditions fall within their capabilities.

What Is the Difference Between Pusher and Bellows Seals?

Pusher Seals (Spring-Loaded)

Pusher seals use springs to maintain contact between the seal faces, with a dynamic O-ring that slides along the shaft or sleeve to accommodate wear and axial movement.

The springs can be a single large coil or multiple smaller springs arranged around the seal circumference. Multiple springs distribute the load more evenly and are less sensitive to shaft deflection, which is why they’re more common in process applications.

Pusher seals dominate general industrial pumping because they’re economical, versatile, and available from numerous suppliers in a wide range of sizes. When a maintenance technician needs a replacement seal quickly, a pusher design is usually the easiest to source.

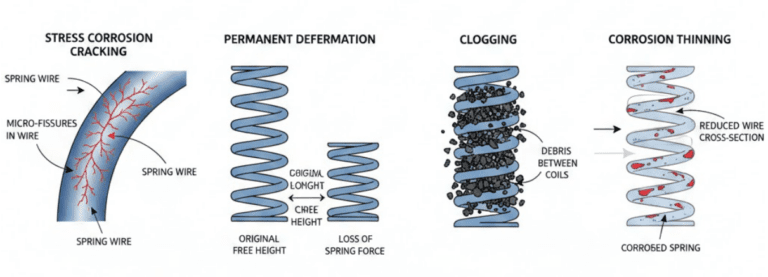

The weaknesses of pusher seals trace back to that sliding O-ring. As the seal faces wear and the spring pushes the rotating assembly forward, the O-ring must slide along the shaft or sleeve. This creates two problems:

Hangup occurs when the O-ring sticks in place instead of sliding smoothly. Process fluid crystallizing behind the seal, corrosion on the shaft surface, or swelling of the elastomer can all cause the O-ring to bind. When this happens, the spring can no longer compensate for face wear, and the seal fails.

Fretting is the wear damage caused by the O-ring’s small cyclic movements under the seal as the shaft rotates. Over time, this creates grooves in the shaft or sleeve that make hangup more likely and can themselves become leakage paths.

Temperature limits pusher seals to around 150°C for most elastomer materials. Higher temperatures require special O-ring compounds that may compromise chemical resistance or flexibility.

For general-purpose pumping, moderate temperatures, and applications where cost matters more than absolute reliability, pusher seals remain the standard choice.

Bellows Seals (Non-Pusher)

Bellows seals replace the spring and sliding O-ring with a flexible metal or elastomeric bellows that provides both spring force and a static secondary seal. The bellows flexes to accommodate wear without any sliding parts.

This eliminates hangup and fretting entirely. No sliding O-ring means no friction damage to shafts, no sticking, and no dependency on perfect shaft surface finish.

Metal bellows seals can operate at temperatures up to 425°C with appropriate face materials. The all-metal construction tolerates temperature ranges that would destroy elastomeric O-rings. For high-temperature applications—hot oil, thermal fluid, some chemical processes—bellows seals are often the only viable option.

The bellows design is also more forgiving of dirty or crystallizing process fluids. Deposits that would cause a pusher seal to hang up don’t affect a bellows seal the same way—there’s no sliding interface to bind.

The tradeoffs are real though. Bellows seals cost more than equivalent pusher designs. The thin metal bellows can be damaged by mishandling during installation. Size availability is more limited than for pusher seals. And while the bellows itself is robust in operation, physical damage from dropping the seal or impact during installation can cause immediate failure.

For high-temperature service, chemical environments where hangup is likely, or applications where seal reliability is critical enough to justify the premium, bellows seals are worth the investment.

Should You Choose Cartridge or Component Seals?

| Feature | Cartridge Seal | Component Seal |

|---|---|---|

| Initial cost | 2-3x higher | Lower |

| Installation time | 60% faster | Longer |

| Skill required | Basic | Skilled technician |

| Installation error risk | Low | Higher |

| Pre-set spring tension | Yes | Must be set in field |

| Factory tested | Yes | No |

| Pump compatibility | More limited | Wider |

| Spare parts cost | Higher | Lower |

Cartridge Mechanical Seals

Cartridge seals come as complete, pre-assembled units that include the seal, sleeve, gland plate, and all necessary hardware in a single package. Installation means sliding the assembly onto the shaft and bolting it in place.

No measurements required. No calculations for spring setting. No risk of forgetting a component or installing things in the wrong order. The seal arrives ready to run, with spring tension pre-set and the whole assembly factory-tested under pressure.

This simplicity translates directly to reliability. Studies consistently show that cartridge seals have lower failure rates than component seals, primarily because installation errors drop dramatically. Even technicians with limited mechanical seal experience can install a cartridge seal successfully.

The time savings are substantial. Where a component seal installation might take two hours, a cartridge seal installation often takes 45 minutes. In plants where downtime costs thousands of dollars per hour, that difference pays for the seal premium several times over.

Cartridge seals fit naturally into critical applications—services where seal failure causes safety incidents, environmental releases, or major production losses. Pharmaceutical manufacturing, hazardous chemical processing, and continuous operations with high uptime requirements commonly standardize on cartridge seals.

The higher upfront cost is the obvious downside. Cartridge seals typically cost two to three times more than equivalent component seals. Spare parts and replacements cost proportionally more too. And not every pump can accept a cartridge seal—some stuffing box configurations and limited space envelopes require component-style installation.

Component Mechanical Seals

Component seals arrive as individual parts that maintenance technicians assemble onto the pump. This requires measuring the seal chamber dimensions, calculating the correct spring setting, and carefully assembling each element in the proper sequence.

When everything goes right, a component seal performs identically to a cartridge seal. The lower initial cost makes them attractive for general-service applications where seal failures cause inconvenience rather than catastrophe.

Component seals also fit more pumps. Since the parts install individually, they can work in tight spaces and unusual configurations that won’t accommodate a bulky cartridge assembly. Older pumps designed before cartridge seals became popular often require component installations.

Stocking component seal parts—faces, O-rings, springs—costs less than stocking complete cartridge assemblies. A maintenance storeroom can support many different pumps with a modest inventory of common parts.

The risk is installation error. Incorrect spring setting is the most common mistake—too much compression overloads the faces and causes rapid wear; too little compression allows leakage from the start. Contaminating the seal faces during installation, damaging O-rings, or incorrect positioning all lead to premature failure.

Plants with experienced seal technicians and established maintenance procedures can achieve excellent results with component seals. But if your maintenance team changes frequently, training is limited, or critical pumps need to run without downtime for quality control, cartridge seals reduce your risk.

How Do You Select the Right Mechanical Seal?

Step 1: Determine Single vs. Double Seals

The first decision is containment level. Do you need a single line of defense or two?

Choose a single seal when your pumped fluid isn’t hazardous and environmental release isn’t a concern. Water, light oils, and general-purpose chemicals in typical industrial applications work fine with single seals. The simplicity and lower cost make single seals the standard choice.

Upgrade to double seals when you’re pumping toxic chemicals, flammable hydrocarbons, expensive specialty fluids, or any liquid where environmental release would create regulatory, safety, or financial consequences. Hazardous chemical plants, petroleum refineries, and pharmaceutical manufacturing routinely require double seals.

Regulations often force the decision. Check environmental and safety requirements for your specific fluid before choosing single seals for critical applications.

Step 2: Choose Between Balanced and Unbalanced Based on Pressure

Pressure is the primary driver of this decision.

Balanced seals are the clear choice for applications above 200 PSIG. The stepped design reduces face loading, which means less friction, less heat, and longer service life. Any service with challenging fluids, poor lubricity, or high vapor pressure fluids benefits from balanced seals, even at lower pressures. The higher initial cost is justified by extended service life.

Unbalanced seals work fine below 200 PSIG in stable operating conditions. The simpler design makes them less expensive and easier to source. They’re also more resistant to opening under vibration and shaft deflection, which can be an advantage in rough operating environments.

Between 100-200 PSIG, evaluate your specific conditions. If fluids are demanding or operating conditions stressful, upgrade to balanced seals even at lower pressures.

Step 3: Select Pusher or Bellows Based on Temperature and Reliability Needs

This choice depends on operating temperature and how critical seal reliability is.

Pusher seals are the economical standard for general-purpose applications. They handle temperatures up to about 150°C with standard elastomers. Most industries—water treatment, HVAC, general manufacturing—use pusher seals successfully.

Choose pusher seals when cost matters, temperatures are moderate, and your maintenance team can handle routine installations. Most replacement seals available quickly are pusher designs.

Bellows seals are necessary for high-temperature service above 150°C. Metal bellows can tolerate temperatures up to 425°C with appropriate face materials. Bellows seals also eliminate the hangup and fretting problems that sometimes plague pusher seals in dirty applications or with crystallizing fluids.

Upgrade to bellows seals for high-temperature service, critical applications where seal reliability directly affects safety or production, or situations where hangup has caused past failures. The premium cost is justified by superior performance in demanding conditions.

Step 4: Decide on Cartridge vs. Component Assembly

This decision balances installation simplicity against cost and flexibility.

Cartridge seals come pre-assembled and factory-tested. Installation is straightforward—no measurements, no calculations, minimal skill required. Downtime is shorter and installation errors are rare.

Specify cartridge seals for critical applications where seal failure has serious consequences, facilities with less experienced maintenance teams, or where installation speed matters (every minute of downtime is expensive). The 2-3x cost premium is easily justified when it reduces downtime from 2 hours to 45 minutes.

Component seals consist of individual parts assembled on-site. This requires more skill and takes longer but costs less and fits more pump configurations. Component seals work well in established maintenance operations with experienced technicians.

Use component seals when flexibility matters (unusual pump configurations), spare parts strategy drives decisions (stocking common parts for various pumps), or installation labor is in-house and highly skilled.

Step 5: Match Seal Type to Application Requirements

Now combine your decisions into a specification.

Standard industrial applications (water, light oils, moderate temperatures, pressures below 200 PSIG): Single seal, unbalanced, pusher design, component or cartridge based on your maintenance capability. Cost is minimal; reliability is proven.

High-pressure applications (above 200 PSIG with demanding fluids): Single seal, balanced, pusher or bellows depending on temperature, cartridge design for critical service. The balanced design handles pressure stress; pusher works if temperatures are moderate; bellows if temperatures are high.

Hazardous chemical service (toxic, flammable, or restricted-release fluids): Double seal with barrier fluid system (Plan 53 or 54), balanced design to minimize heat, cartridge installation for installation quality. Environmental and safety regulations usually drive this choice.

High-temperature service (above 150°C): Single or double seal depending on containment needs, balanced design for pressure control, bellows instead of pusher to handle temperature, cartridge for reliability. Metal bellows eliminate elastomer limitations.

Slurry and abrasive applications (solids-laden process fluids): Double seal with external flush system (Plan 32), balanced design, hard face materials (silicon carbide), cartridge assembly. The flush system keeps abrasives away from the sealing interface.

Calculate total cost of ownership for your specific application. A more expensive seal that runs 3 years costs less than a cheap seal that fails every 18 months. Include downtime costs in your analysis—they often exceed equipment costs many times over.