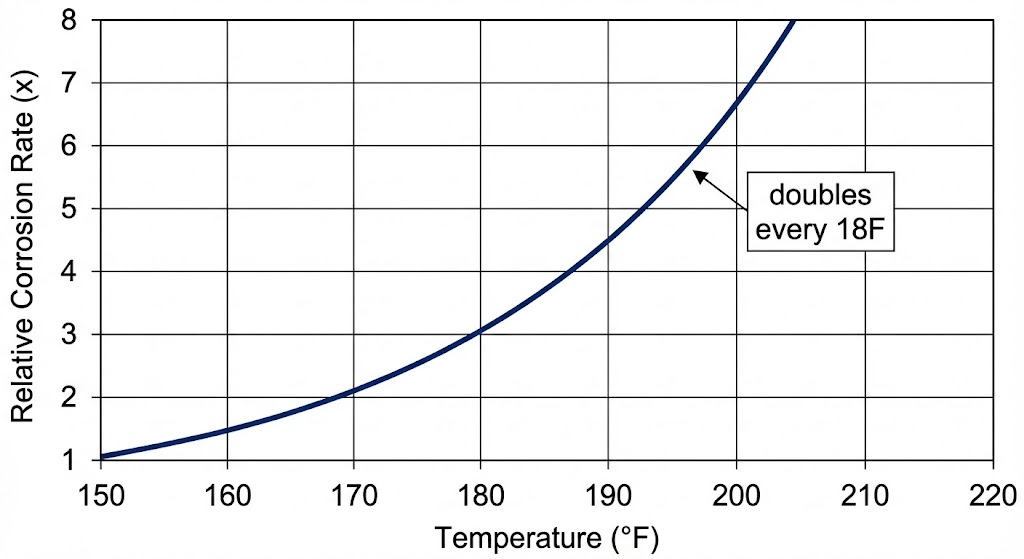

Every 18F increase in seal chamber temperature doubles the corrosion rate attacking your mechanical seal. A 36F difference means four times the chemical aggression. I’ve analyzed hundreds of chemical pump seal failures over the past 15 years, and the pattern is consistent: plants upgrade to expensive alloys while ignoring the temperature differential that’s accelerating the attack.

One practitioner on an engineering forum put it perfectly: “I installed a 316 SS pump in 98% sulfuric acid at 70F and had the case corrode through in 3 weeks. In that pump, there were areas within the pump where the temperature was much higher.” The spec sheet said 316 SS was compatible. The seal chamber disagreed.

This guide shows you how to protect mechanical seals in chemical pump applications by controlling the operating environment first and selecting materials second. The API 682 standard supports this approach, and decades of refinery experience prove it works.

Why Chemical Pumps Destroy Seals Despite “Correct” Material Specs

The seal chamber environment determines corrosion behavior more than the material selection alone.

I’ve seen this failure pattern dozens of times: a chemical plant specifies Alloy 20 seals for sulfuric acid service, expecting premium corrosion resistance. Then the seals fail repeatedly. A peer-reviewed case study in the Engineering Failure Analysis journal documented exactly this scenario at a nitrobenzene production facility. Four sulfuric acid pumps experienced 8 mechanical seal failures and over 30 maintenance interventions in a single year, despite using Alloy 20 materials specified for corrosion resistance.

The investigation revealed the real problem. Visual inspection, SEM, and EDS analysis showed the sealing gland’s chemical composition didn’t meet Alloy 20 standards. Galvanic corrosion developed between dissimilar materials, and intergranular corrosion attacked the sealing gland where it contacted the static ring seat.

What the spec sheet doesn’t tell you is that material selection is only half the equation. Even when you get the material right, the seal chamber conditions can overwhelm your corrosion resistance. Temperature, pressure, and fluid dynamics in the seal chamber often differ dramatically from the bulk process conditions you’re designing against.

The industry consensus focuses on material compatibility charts and alloy upgrades. Competitors provide extensive tables matching chemicals to seal materials. But these approaches share an implicit assumption: get the material right, and the seal will survive. Field experience tells a different story.

The Temperature Effect Most Engineers Overlook

Corrosion rate doubles for every 10C (18F) rise in temperature. This is the Arrhenius rule, established in physical chemistry and validated across countless industrial applications.

The math is straightforward but the implications are dramatic. If your seal chamber runs 36F hotter than expected, you face four times the chemical attack rate. A seal designed for 5-year life at 150F might fail in 15 months at 186F. Most chemical pump seal failures I investigate trace back to this overlooked factor.

According to Chemistry LibreTexts, this temperature dependence is “a widely used rule-of-thumb for the temperature dependence of a reaction rate.” It’s not an exact law for every chemical reaction, but it’s reliable enough that API 682 builds its recommendations around it.

Seal chambers run significantly hotter than discharge temperature for several reasons. Heat soak transfers energy from the hot pump casing into the seal chamber fluid. Friction between seal faces generates additional heat. Poor circulation traps heated fluid in the seal chamber.

The heat soak calculation reveals the scale of this problem. According to seal engineering references, the formula is Hs = 12S x (pump temp – seal chamber temp), where S is the seal size in inches. A 3.5-inch dual seal in a 500F pump with a 150F barrier fluid target produces 14,700 Btu/hr of heat soak. That thermal load must go somewhere, and if your cooling capacity is inadequate, the seal chamber temperature rises until something fails.

Before upgrading materials, measure your seal chamber temperature. I recommend installing a thermowell in the seal gland for critical chemical services. The data often reveals temperature differentials that explain chronic failures better than any compatibility chart.

Corrosion Types in Chemical Service

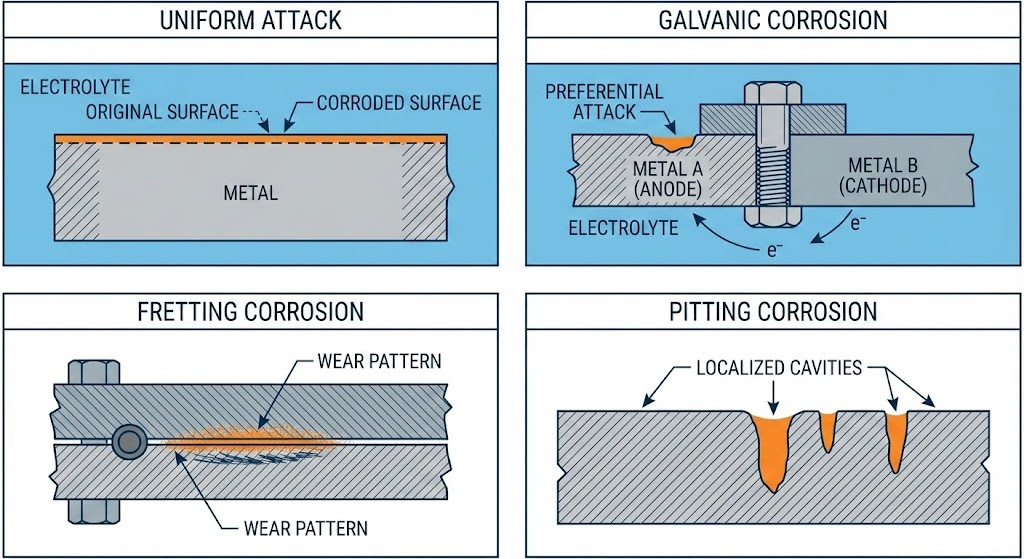

Different corrosion mechanisms respond differently to temperature control versus material changes. Understanding which type you’re fighting determines your defense strategy.

Uniform Chemical Attack

The aggressive chemical dissolves seal materials at a predictable rate across exposed surfaces. Temperature accelerates this dramatically through the Arrhenius effect. Lowering seal chamber temperature by 36F cuts the attack rate to one-quarter. Material upgrades also help, but temperature control often achieves the same result at lower cost.

Galvanic Corrosion

When dissimilar metals contact each other in an electrolyte, the more active metal corrodes preferentially. The nitrobenzene pump case study documented this failure mode: galvanic corrosion between seal components that weren’t properly matched. Temperature affects galvanic corrosion rates, but material pairing is the primary defense. Ensure all metallic seal components fall within the same galvanic series range.

Fretting Corrosion

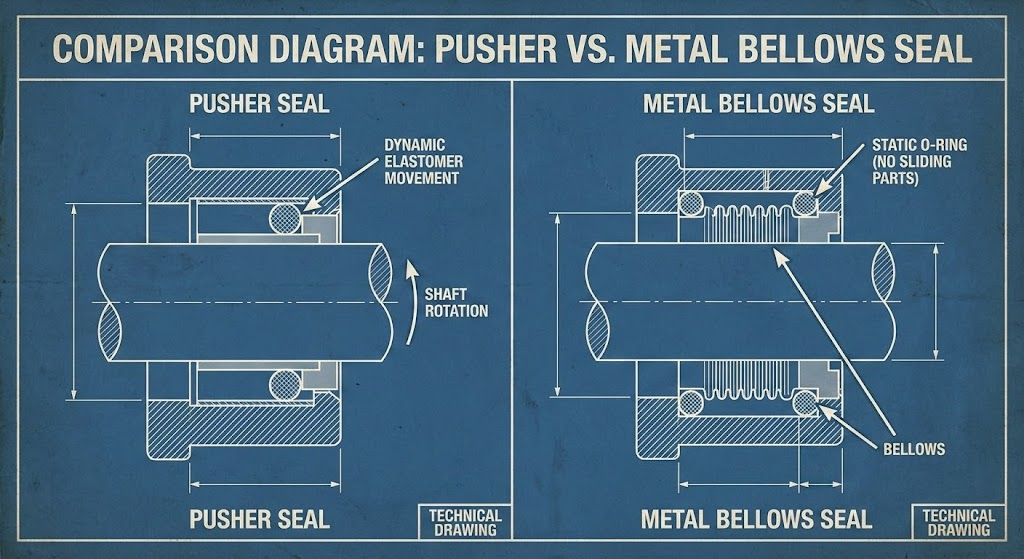

This is the most underdiagnosed failure mode in chemical service. According to practitioners on engineering forums, fretting damage comes from “movement of the dynamic elastomers” due to “run-out on the seal chamber face.” Each shaft rotation causes the O-ring to slide slightly, removing the passive oxide coating that normally protects the sleeve from corrosion.

Fretting corrosion is primarily a mechanical problem, not a chemical one. Temperature control helps somewhat by reducing elastomer stiffness, but eliminating dynamic elastomer movement is the real solution. This is why bellows seals use static secondary seals that don’t move during operation.

Pitting Corrosion

Localized attack creates small cavities that penetrate deep into the material while leaving surrounding surfaces relatively intact. A sour condensate NGL pump case study documented this failure mode: pitting corrosion in O-ring surfaces caused a 7-month mean time between failures. Pitting often starts at surface defects or inclusions, making material quality and surface finish critical.

Temperature Control Methods That Actually Work

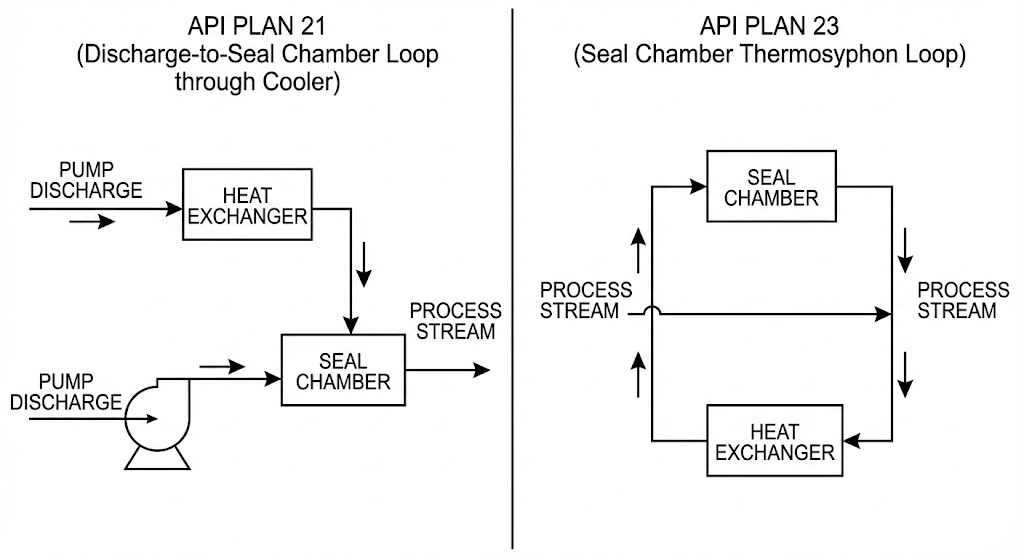

API 682, the governing standard for pump shaft sealing systems, recommends flushing the seal to limit chamber temperature increase to less than 10F. The standard prefers temperature reduction over pressure increase for managing vapor pressure margin.

Plan 21 vs Plan 23 Comparison

Plan 21 recirculates process fluid from the pump discharge through a heat exchanger and back to the seal chamber. It’s effective but inefficient because it cools the entire process stream, not just the seal chamber fluid.

Plan 23 circulates only the fluid in the seal chamber through a heat exchanger using thermosyphon action. According to seal manufacturers including Flowserve and AESSEAL, Plan 23 provides the most effective and efficient cooling for mechanical seals. Typical temperature reductions range from 20F to 50F depending on application conditions.

The efficiency difference matters because Plan 23 removes only seal face heat and heat soak, not bulk process heat. This targeted approach achieves the same seal chamber temperature with smaller heat exchangers and lower utility costs.

Plan 23 is the most underutilized tool in chemical service. I’ve converted dozens of chronic failure applications from Plan 21 to Plan 23 and seen immediate improvement. One distillery documented their experience: converting from single seals with external flush (Plan 32) to double seals with Plan 53A eliminated seal failures while significantly increasing production throughput.

API 682 Temperature Limits

The standard specifies that vapor pressure margin in the seal chamber shall be a minimum of 50 psi, or a minimum ratio of 1:3 between absolute pressure and absolute vapor pressure. For water-based buffer and barrier fluids, the allowable temperature rise is 15F.

These aren’t arbitrary numbers. They reflect decades of field experience showing where seals survive long-term versus where they fail prematurely.

Dual Seal Options for Severe Service

When single seals can’t maintain adequate vapor pressure margin, dual seals with barrier or buffer systems provide an additional defense layer. Plan 52 uses an unpressurized buffer fluid for services where minor process leakage is acceptable. Plan 54 uses a pressurized barrier fluid for hazardous services where zero process leakage is required.

The barrier or buffer fluid also provides thermal isolation between the hot process and the outboard seal. This additional cooling effect can extend seal life in high-temperature services significantly.

Refinery best practices dating to the mid-1970s demonstrate what’s achievable: proper flush plan selection routinely delivers multiple years of reliable seal operation for bottoms and gas oil pump applications.

Material Selection: What Temperature Control Cannot Fix

Temperature control reduces corrosion rate but cannot change fundamental material compatibility. When the chemical attacks the seal material through mechanisms that don’t respond to temperature, material upgrades become necessary.

When Material Upgrades Are Necessary

Highly oxidizing chemicals like nitric acid and chlorine require specific alloys regardless of temperature. Strong alkalis above pH 11 attack silicon carbide seal faces, requiring conversion to tungsten carbide or ceramic alternatives. Hydrofluoric acid service demands Hastelloy C or specialized alloys that resist fluoride attack.

Material selection becomes primary defense when the chemical reacts with the seal material at any temperature you can practically achieve in the seal chamber.

Elastomer Selection

Elastomers often fail before hard seal faces in chemical service. FKM (Viton) handles most hydrocarbon services but degrades in ketones, esters, and strong amines. EPDM resists water, steam, and many polar solvents but swells in hydrocarbons. FFKM (Kalrez, Chemraz) offers the broadest chemical resistance but at 10-20x the cost of FKM.

Match your elastomer to the worst chemical in your process stream, not just the primary fluid. Trace contaminants cause more elastomer failures than bulk chemicals.

Standard Testing Limitations

If your seal fails in the first 60 days, blame the material. After that, blame the environment.

Industry research suggests that standard 28-day compatibility testing may miss a significant portion of materials that ultimately fail in service. ASTM D2000 requires only 70 hours of exposure, far less than the months or years of service life you’re designing for. Extended testing (60-90 days) reveals failures that standard testing misses.

This uncertainty argues for conservative material selection combined with robust environmental control. If temperature management can achieve your reliability targets with standard materials, you avoid the risk that exotic alloys still fail due to undetected long-term incompatibility.

Seal Architecture for Corrosive Service

The mechanical design of the seal affects corrosion resistance independent of material selection.

Bellows vs Pusher Seals

Pusher seals use a dynamic elastomer (O-ring or wedge) that slides along the shaft sleeve as the seal faces wear. This movement creates fretting corrosion risk in corrosive chemicals. According to AESSEAL, “The major advantage of using a metal bellows seal is the removal of a semi-dynamic sliding elastomer from a conventional pusher type mechanical seal. This removes the potential for mechanical seal hang-up or shaft/sleeve fretting.”

Bellows seals are non-negotiable for corrosive service with shaft runout. If your pump exhibits detectable runout at the seal chamber face, the dynamic elastomer in a pusher seal will move with each rotation, scrubbing away protective oxide layers and initiating fretting corrosion. Bellows seals eliminate this failure mode by using a static secondary seal that doesn’t move during operation.

Double vs Single Seals

Double seals provide a barrier between the process fluid and atmosphere. In corrosive service, the barrier fluid can be selected for compatibility with both the process and the outboard seal materials. This isolates the outboard seal from the corrosive process entirely.

Cartridge seals simplify installation and eliminate field measurement errors that can cause premature failure. For API 682 compliance in chemical service, pre-assembled cartridge seals reduce the risk of installation-induced failures.

API 682 Seal Type Classification

API 682 classifies seals into Type A (pusher, unbalanced), Type B (pusher, balanced), and Type C (bellows). For corrosive service:

- Type A: Low-pressure, mild corrosives where fretting risk is minimal

- Type B: Higher pressure, moderate corrosives with adequate shaft concentricity

- Type C: Corrosive service with any shaft runout, or where hang-up risk exists

The standard specifies Type C seals for services where the dynamic elastomer would be exposed to conditions causing hang-up or excessive wear.

Root Cause Analysis When Seals Still Fail

Material selection and temperature control address the majority of corrosion-related failures, but operational factors cause failures that look like corrosion but aren’t.

The Oceaneering 40-Pump Study

A North Sea oil and gas operator experienced repeated mechanical seal failures across 40 production pumps. They engaged reliability engineers to identify root causes. The investigation found 12 distinct root causes contributing to premature failures. None were material failures.

The actual causes included:

- Operating pumps away from best efficiency point

- Incomplete venting during system startups

- Inconsistent monitoring of seal system operating parameters

- Barrier fluid contamination from improper tank refilling

- Wrong filter specifications on seal systems

The API 682 standard specifies this for a reason: seal reliability depends on the entire system, not just the seal itself.

Diagnostic Checklist

When investigating corrosion-related seal failures, verify:

- Temperature differential: Measure actual seal chamber temperature versus process temperature

- Barrier/buffer fluid condition: Check for contamination, degradation, or incorrect fluid

- Pump operating point: Confirm operation within 70-120% of best efficiency point

- Startup procedures: Verify complete venting before starting

- Material verification: Confirm installed materials match specification (SEM/EDS analysis if necessary)

- Surface condition: Inspect for fretting marks, pitting patterns, or uniform erosion

Before replacing the seal, check the operating conditions. Many “corrosion” failures are actually thermal, mechanical, or operational problems that corrode the evidence after the initial damage occurs.

Key Takeaways

Temperature control in the seal chamber prevents more corrosion failures than material upgrades. This isn’t theory; it’s demonstrated by the Arrhenius rule (corrosion doubles every 18F), API 682 recommendations, and decades of refinery best practice.

Environment first. Materials second. That’s how you protect mechanical seals in chemical service.

For complex applications where standard approaches haven’t delivered the reliability you need, request an application review. Sometimes the combination of temperature, pressure, chemistry, and pump dynamics requires a customized solution.