If you’ve ever wondered how pumps, compressors, and industrial mixers keep their fluids from leaking out along a spinning shaft, the answer is mechanical seals. These precision devices sit at the heart of countless industrial operations, solving a problem that seems simple but is surprisingly complex: how do you prevent fluid from escaping when a shaft must rotate freely?

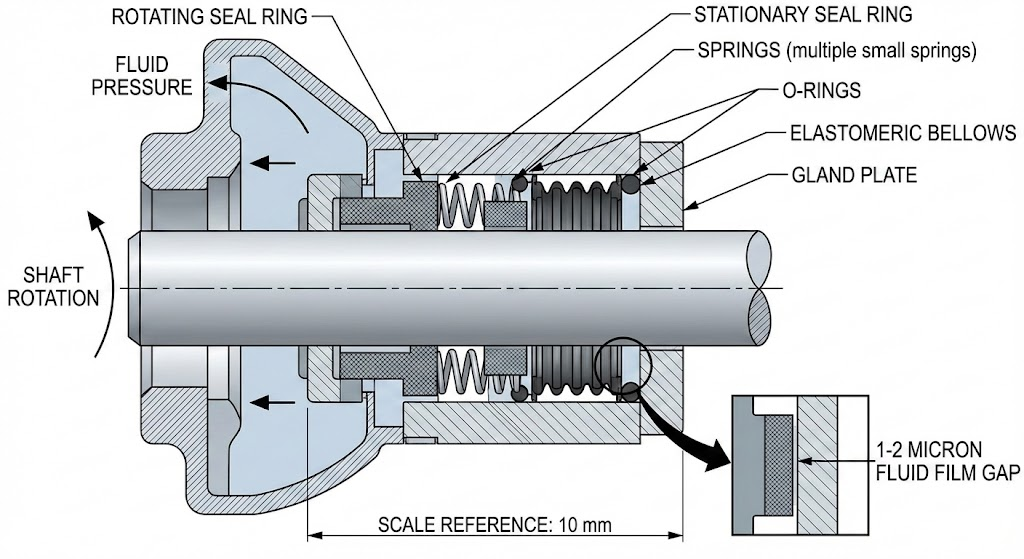

A mechanical seal is a precision-engineered sealing device that stops fluid leakage around rotating shafts in industrial equipment. It accomplishes this using two extremely flat surfaces—one spinning with the shaft and one stationary—that press against each other with spring-force precision. The gap between these faces is so small (as little as 1 micron, or 75 times narrower than a human hair) that fluid can barely squeeze through, creating an almost-perfect seal.

What Problem Does a Mechanical Seal Solve?

Every centrifugal pump faces the same fundamental challenge: the rotating shaft must pass through the stationary pump housing. That interface is where leakage wants to happen.

Traditional gland packing addressed this problem for decades. Braided rings of material wrapped around the shaft, compressed by a gland follower. Simple and cheap. But packing has serious drawbacks.

Packing requires constant contact with the shaft to reduce leakage. This friction generates heat and wears a groove into the shaft over time. You’ll burn through approximately 1,200 gallons of flush water per year on a 2-inch shaft just to keep packing cool—and real-world leakage rates often run 5-10 times higher than the theoretical minimum.

Packing also consumes 6 times more power than a balanced mechanical seal. Running pumps with packing is like driving with your parking brake on.

Mechanical seals solve these problems through a completely different approach. Instead of friction-based sealing, they create a controlled micro-gap between precision-machined surfaces. Leakage drops to roughly 10 drops per hour or less. Energy consumption plummets. And properly installed seals can run 10+ years without adjustment.

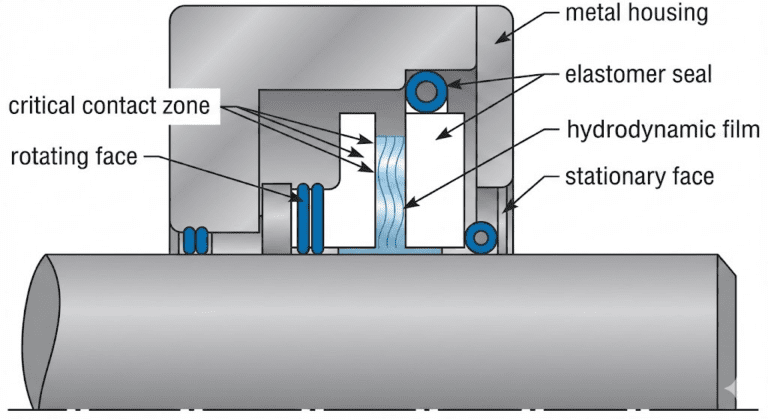

The Basic Principle: Two Faces, One Thin Film

Mechanical seals work on an elegant principle. Two extremely flat surfaces—one rotating at shaft speed and one fixed in place—are pressed together by springs and hydraulic pressure. Between these faces flows a microscopic fluid film, approximately 2 microns thick.

This film is critical. Without it, the metal or ceramic faces would grind against each other, generating devastating friction and heat. With it, the seal operates smoothly for years. The fluid film comes either from the fluid being pumped or from an external support system, depending on the application.

The pressure that keeps the faces together comes from two sources: the hydraulic pressure of the sealed fluid and the mechanical force of springs. This balance is everything. Too little pressure and fluid leaks past. Too much and the seal faces wear rapidly.

What Are the Core Components of a Mechanical Seal?

Every mechanical seal contains the same basic elements, regardless of manufacturer or configuration.

| Component | Function | Typical Materials |

|---|---|---|

| Rotating seal face | Spins with shaft, provides one sealing surface | Carbon graphite, silicon carbide |

| Stationary seal face | Fixed to housing, provides mating surface | Silicon carbide, tungsten carbide, ceramic |

| Spring mechanism | Maintains closing force on faces | Stainless steel, Hastelloy |

| Secondary seals | Prevent leakage at static interfaces | O-rings (elastomers), PTFE wedges |

| Drive mechanism | Transmits rotation from shaft to rotating face | Set screws, drive pins, sleeves |

The seal faces are the heart of the system. They’re lapped to optical flatness—typically 2-3 Helium light-bands, which translates to 0.0008mm or about 0.00003 inches. That’s flatter than you can achieve with any conventional machining process.

This extreme flatness prevents liquid from flowing between the faces. It’s not a gasket seal or a compression seal. It’s a precision interface where the surfaces are so perfectly matched that fluids simply can’t pass through.

How It All Works Together

Here’s the sequence: When the shaft rotates, the rotating seal ring rotates with it because it’s attached to the shaft. The stationary seal ring remains fixed inside the housing. The springs push these rings together.

The sealed fluid between the faces creates hydraulic pressure that pushes back against the springs, creating equilibrium. A thin film of fluid forms between the rotating and stationary faces. This film is your seal.

As the rotating face spins, it drags fluid with it through viscous shear, constantly replenishing the film. The film prevents the faces from touching directly, eliminating direct metal-to-ceramic friction. Temperature and pressure remain controlled, the fluid film stays intact, and the seal remains effective.

If the pump stops, springs alone hold the faces together. If the pump starts again, hydraulic pressure resumes. If something goes wrong—contamination gets in, alignment shifts, or the seal runs dry—the film breaks down, temperatures spike, and the seal fails. This is why mechanical seals demand such careful installation and maintenance.

What Are the Main Types of Mechanical Seals?

What Is the Difference Between Pusher and Non-Pusher Seals?

The distinction comes down to how the seal compensates for face wear.

| Feature | Pusher Seals | Non-Pusher (Bellows) Seals |

|---|---|---|

| Secondary seal | Dynamic O-ring slides on shaft | Static—bellows flexes |

| Spring type | Single coil, multiple springs, or wave springs | Bellows acts as spring |

| Cost | Lower | Higher |

| Temperature limit | Limited by O-ring material (~400°F typical) | Up to 800°F with metal bellows |

| Shaft corrosion tolerance | Poor—O-ring can hang up | Excellent—no sliding contact |

| Best applications | General service, clean fluids | High temp, crystallizing, or corrosive fluids |

Pusher seals dominate general industrial applications because they’re cheaper and available in more configurations. I’d estimate 70% of the seals in a typical refinery or chemical plant are pusher designs.

But when the application gets difficult—hot oil, crystallizing caustic, or services where the shaft might corrode—bellows seals pay for themselves quickly.

When Should You Use Balanced vs. Unbalanced Seals?

Balance ratio is the ratio of the closing area (where sealed pressure pushes the faces together) to the opening area (the actual face area where fluid pressure acts to separate the faces).

Unbalanced seals have a balance ratio greater than 1.0. The full sealed pressure acts on the closing side, creating high face loading. They’re stable and resistant to vibration, but they generate more heat and wear faster under pressure.

Balanced seals have a balance ratio between 0.65 and 0.85. A step or shoulder on the seal ring reduces the area exposed to closing pressure. This drops face loading significantly, reducing heat generation and extending seal life.

The practical cutoff: use unbalanced seals below 250 psid sealed pressure. Above that, you need balanced designs. API 682—the standard for seals in petroleum and chemical service—requires balanced seals for all applications.

How Do Single and Double Seal Arrangements Differ?

A single seal has one pair of faces and vents directly to atmosphere. Simple, cheap, and suitable for most non-hazardous services.

Double seals add a second pair of faces, creating a barrier chamber between the process fluid and atmosphere. This chamber contains a barrier fluid—typically a clean, compatible liquid at higher pressure than the process.

If the inboard seal fails, the barrier fluid leaks into the process instead of process fluid leaking to atmosphere. If the outboard seal fails, barrier fluid leaks out—but it’s generally a safer fluid than what you’re pumping.

Double seals are mandatory for hazardous, toxic, or flammable fluids where any atmospheric release is unacceptable. They’re also required when the process fluid has poor lubricating properties or would damage a single seal.

The trade-off is complexity and cost. Double seal systems need barrier fluid reservoirs, circulation systems, and monitoring instrumentation. API 682 piping plans like Plan 52 (unpressurized buffer) or Plan 53A (pressurized barrier) define how to configure these systems.

What Materials Are Used for Seal Faces?

Face material selection determines seal life more than almost any other factor. Get it wrong, and you’ll be pulling seals monthly. Get it right, and the same seal design runs for years.

| Material | Mohs Hardness | Max Temperature | Thermal Conductivity | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon graphite | 1-2 | 350°C (660°F) | 5-8 BTU/hr-ft-°F | General service, self-lubricating |

| Reaction-bonded SiC | 9-9.5 | >500°C (930°F) | 40-100 BTU/hr-ft-°F | Abrasive media, high pressure |

| Direct-sintered SiC | 9-9.5 | >500°C (930°F) | 40-100 BTU/hr-ft-°F | Corrosive chemicals |

| Tungsten carbide | 9 | High | 30-50 BTU/hr-ft-°F | Extreme abrasion |

| Alumina ceramic | 9 | High | 10-15 BTU/hr-ft-°F | Chemical resistance |

The most common pairing in industrial applications is carbon graphite running against silicon carbide. Carbon provides self-lubrication and conformability. Silicon carbide provides hardness and wear resistance. They complement each other well.

For abrasive services—slurries, fluids with suspended solids—you’ll need silicon carbide against silicon carbide. Both faces must resist the grinding action of particles passing through. These hard-on-hard pairings run hotter and need excellent lubrication, but they’ll survive conditions that would destroy softer materials in hours.

Mechanical Seals vs. Gland Packing

Compared to gland packing, mechanical seals win decisively on every metric that matters. Packing leaks 1 to 5 gallons per hour while mechanical seals leak 0.1 to 0.5. Packing needs adjustment every 3 to 6 months and replacement every 12 to 18 months. Mechanical seals can run 3 to 5 years without intervention.

Energy efficiency tells the story: mechanical seals reduce energy consumption by 2 to 3% compared to packing. In a facility with hundreds of pumps running continuously, this translates to thousands of dollars in annual savings.

The only advantage packing retains is ease of installation for retrofits and the ability to adjust it while the pump operates. For applications handling abrasive slurries with sand or crystals, packing is sometimes preferred because replacing damaged packing is cheaper than replacing damaged seal faces.

The Bottom Line

Mechanical seals work through an elegant balance of forces. Spring pressure and hydraulic pressure push precision-lapped faces together. Fluid film pressure pushes them apart. The result is a microscopic gap—roughly 2 microns—that allows just enough leakage to lubricate the faces while preventing significant fluid escape.

Understanding this principle changes how you approach seal selection and troubleshooting. Every decision—material selection, balance ratio, seal arrangement—affects how well the seal maintains that critical fluid film.