I’ve seen pumps fail within weeks of a new seal installation. The culprit? Missing or improperly configured flush systems. The frustrating part is that these failures are almost always preventable.

A flush is simply a fluid introduced into the seal chamber to cool, lubricate, and clean the mechanical seal faces. Think of it as the lifeline that keeps your seal alive. Get it right, and your seals can last years. Get it wrong, and you’re replacing seals every few months.

What Is a Mechanical Seal Flush and Why Does It Matter?

What Exactly Does “Flush” Mean in Seal Terminology?

A flush is a fluid introduced on the process fluid side of the seal, in close proximity to the seal faces. The key word here is “process side.” This distinguishes flush from quench, which operates on the atmospheric side of the seal.

The technical definition from API 682 states it’s “a fluid which is introduced into the seal chamber on the process fluid side in close proximity to the seal faces and typically used for cooling and lubricating the seal faces.”

Flush serves four primary functions:

- Cooling – Seal faces generate significant heat from friction. The flush fluid carries this heat away, preventing thermal damage.

- Lubrication – A thin fluid film forms between the rotating and stationary seal faces. Without this film, the faces grind against each other and wear rapidly.

- Cleaning – The continuous flow sweeps away particles and debris that could scratch or damage the precision-lapped seal faces.

- Pressure Control – Flush maintains higher pressure in the seal chamber than the process side, preventing contaminated process fluid from reaching the seal faces.

Why Do Mechanical Seals Need Flushing?

Mechanical seals generate heat. Every time those two lapped faces spin against each other at 1800 or 3600 rpm, friction creates heat that must go somewhere. Without a flush system to remove that heat, temperatures climb until something fails.

I’ve seen seal faces warp from thermal distortion. I’ve seen carbon faces crack from thermal shock. These aren’t rare occurrences when the flush system isn’t doing its job.

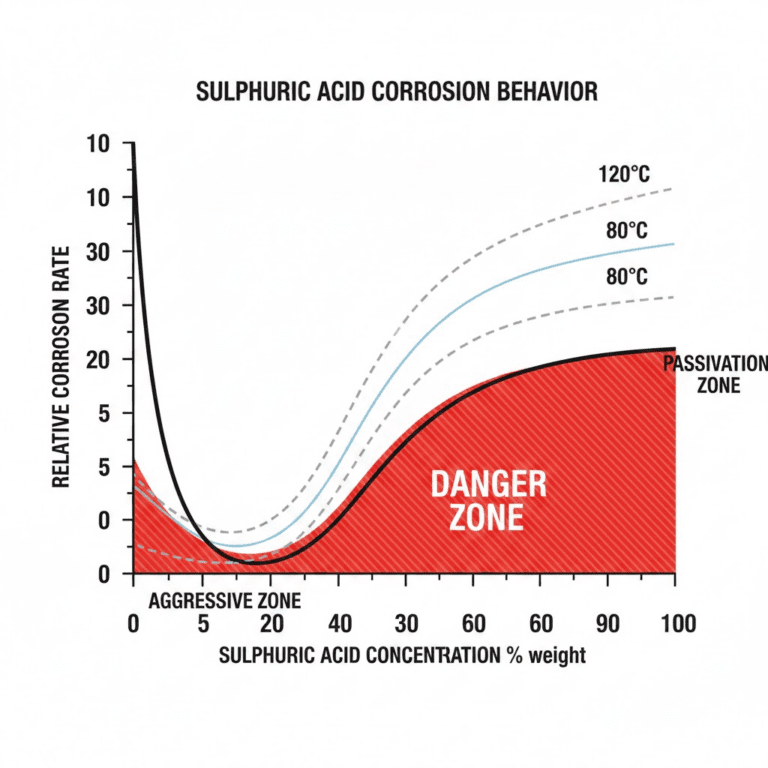

Process fluid contamination is another killer. Abrasive particles in the process stream act like sandpaper on seal faces. Corrosive chemicals attack seal materials. Fluids with poor lubricating properties cause accelerated wear.

A properly designed flush system addresses all these problems. It maintains the seal chamber environment within safe operating limits for temperature, cleanliness, and lubrication.

Not every application requires flushing. Clean water at moderate temperatures with good lubricating properties may seal fine without external flush. But most industrial applications involve at least one complicating factor that makes flush necessary: high temperatures, abrasive particles, corrosive chemicals, or poor lubricity.

How Does a Mechanical Seal Flush System Work?

Step 1: Flush Fluid Introduction

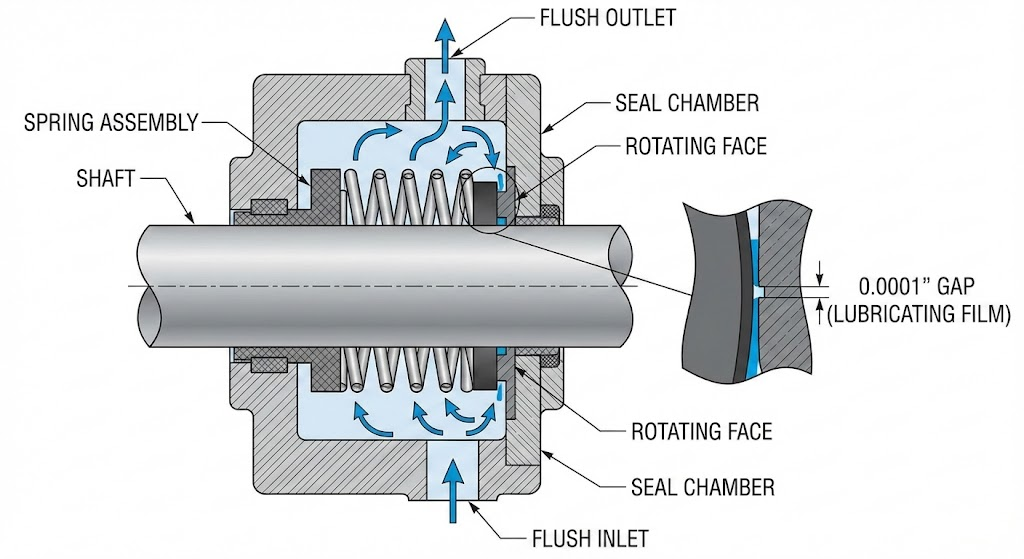

The flush fluid enters through a port on the seal gland plate. This port is positioned to direct flow toward the seal faces where it’s needed most.

Here’s the critical requirement: flush pressure must exceed seal chamber pressure. The typical target is 10-15 psi above seal chamber pressure. This positive pressure differential ensures flush fluid flows across the seal faces rather than process fluid flowing into the seal chamber.

For API Plan 32 external flush systems, the minimum requirement is 15 psi above stuffing box pressure. Some applications push this to 25 psi above seal chamber pressure for added margin.

The flush enters the seal chamber and flows across the seal faces. Tangential entry points work best, with the inlet at the bottom of the gland and outlet at the top. This promotes complete circulation and prevents dead zones where heat can accumulate.

Step 2: Seal Face Cooling and Lubrication

Once the flush fluid reaches the seal faces, it performs two simultaneous functions.

First, it absorbs heat. The friction between rotating and stationary faces generates substantial thermal energy, especially at higher speeds. The flush fluid acts as a heat transfer medium, carrying thermal energy away from the seal faces and into the bulk fluid in the seal chamber.

Second, it creates a lubricating film. The seal faces don’t actually touch during normal operation. A microscopic fluid film, typically 0.0001 inches thick, separates them. This film dramatically reduces friction and wear compared to dry contact.

API 682 recommends limiting seal chamber temperature rise to less than 10°F. If your flush system allows more temperature rise than this, you’re either under-flowing or your inlet temperature is too high.

Step 3: Contaminant Removal and Discharge

The continuous flow of flush fluid sweeps contaminants away from the seal faces. Particles that would otherwise accumulate and cause abrasive damage get flushed out of the seal chamber.

Where does the fluid go? That depends on your piping plan.

In recirculating systems like Plan 11, the flush returns to the pump casing. The fluid continuously cycles: pump discharge to seal chamber, seal chamber back to pump. No external fluid consumption.

In external flush systems like Plan 32, the clean flush fluid mixes with process fluid and exits through the pump. This does consume external fluid, but it keeps contaminated process fluid away from the seal.

The key point is continuous flow. A static fluid pocket won’t cool, lubricate, or clean effectively. You need movement to transfer heat and sweep away contaminants.

What Are the Main Types of Flush Systems?

Internal Flush vs. External Flush: What’s the Difference?

Internal flush uses the process fluid itself. You’re recirculating what’s already in the pump. External flush brings in clean fluid from an outside source.

| Aspect | Internal Flush | External Flush |

|---|---|---|

| Source | Process fluid from pump discharge or casing | Clean fluid from external supply |

| Operating Cost | Lower (uses existing fluid) | Higher (consumes external fluid) |

| Best Applications | Clean, non-abrasive fluids | Dirty, abrasive, or corrosive fluids |

| System Complexity | Simpler (minimal external equipment) | More complex (reservoir, supply lines, controls) |

| Process Dilution | None | Some mixing occurs |

I prefer internal flush whenever the process fluid allows it. Simpler systems have fewer failure points. But when you’re pumping slurry, corrosive chemicals, or fluids that crystallize, external flush becomes necessary to protect the seal.

One limitation of internal flush that catches people off guard: if the process fluid contains solids, centrifugal action concentrates those solids at the pump volute periphery. That’s exactly where Plan 11 draws its flush supply. You end up sending the dirtiest fluid to the seal faces. In these cases, Plan 31 with a cyclone separator or Plan 32 with external flush is the better choice.

Single Flush vs. Double Flush Configurations

A single flush configuration uses one set of seal faces with a flush port. This is the standard setup for most industrial pumps. The flush maintains conditions at that single sealing interface.

Double flush, or dual seal arrangements, use two sets of seal faces with barrier or buffer fluid between them. The flush system maintains fluid circulation through this inter-seal space.

When should you use dual seals with double flush? When single seals can’t provide adequate safety margin. Hazardous fluids, toxic chemicals, and environmentally sensitive products often require dual seals. The barrier fluid provides a second line of defense if the primary seal leaks.

Dual seals with pressurized barrier fluid achieve near-zero emissions. Plan 52 and Plan 53 systems can meet the strictest environmental requirements. But they’re more expensive to install and maintain than single seal configurations.

What Are the Common API Flush Plans?

Which Plans Work for Single Mechanical Seals?

The American Petroleum Institute standardized flush piping arrangements as API 682, now in its 4th edition. These “piping plans” give engineers a common language for specifying seal support systems.

Plan 11 – The default. Recirculates process fluid from pump discharge through an orifice to the seal chamber, then back to the pump. Works for clean fluids with good lubricating properties. This is where you start unless conditions force you to something else.

Plan 13 – Similar to Plan 11, but flow direction reverses. Fluid goes from seal chamber through an orifice to pump suction. Creates lower pressure at the seal faces, which helps with high-temperature services where you want to suppress vaporization.

Plan 14 – Combines Plan 11 and Plan 13. Flow enters from discharge and exits to suction. This self-venting design is ideal for vertical pumps where air pockets can form.

Plan 21 – Plan 11 with a heat exchanger added. For high-temperature services where the process fluid needs cooling before reaching the seal.

Plan 23 – Pumps fluid from the seal chamber through a heat exchanger and back. The seal chamber becomes a closed loop with dedicated cooling. Works well for boiler feed water and other fluids with poor lubricating properties. Typical temperature drops of 20-50°F are achievable.

Plan 32 – External clean fluid injection. For abrasive, corrosive, or contaminated process fluids that would damage seals. The external flush protects the seal by keeping process fluid away from the faces.

Conclusion

Flush systems are the lifeline of mechanical seals. That’s not an exaggeration. The difference between a seal lasting 6 months versus 6 years often comes down to flush system design and maintenance.

Here’s what you should take away:

Pressure matters. Target 10-15 psi above seal chamber pressure. Low pressure allows contamination. High pressure crushes the lubricating film.

Flow matters. Start with 0.5-2.0 gpm per inch of shaft diameter. Adjust based on seal manufacturer recommendations and observed temperature rise.

Plan selection matters. Plan 11 is the default for clean fluids. Plan 32 protects seals from abrasive, corrosive, or contaminated process streams. Don’t force Plan 11 onto applications that need external flush.

Monitoring matters. Pressure and temperature trends catch problems before catastrophic failure. Invest in instrumentation proportional to pump criticality.