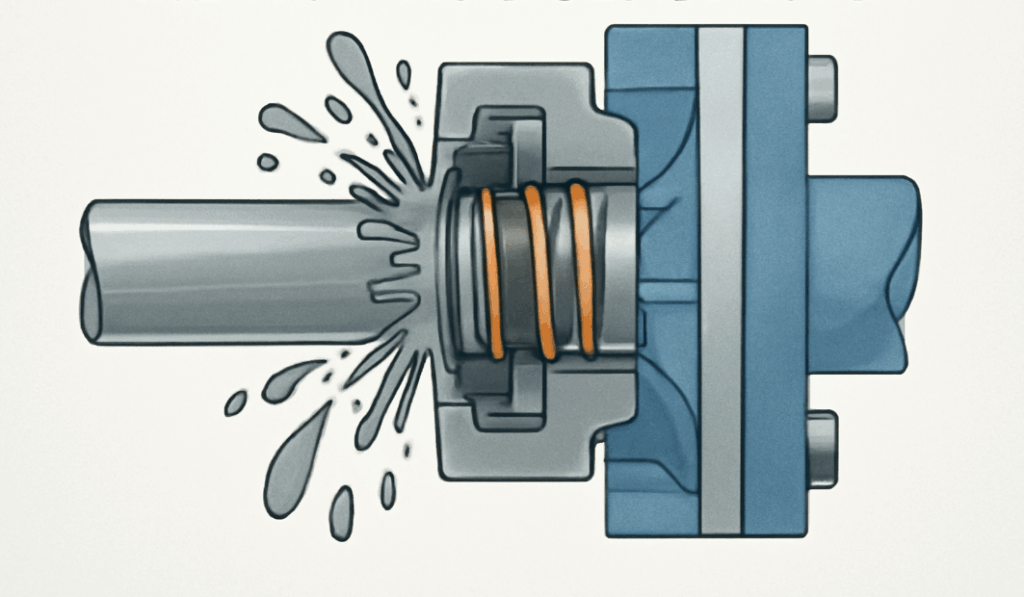

A mechanical seal will typically fail within 10-30 seconds of running completely dry, though some specialized designs can survive up to several minutes. The exact failure time depends on the seal face materials, shaft speed, temperature, and pressure conditions. Without proper lubrication, the seal faces generate extreme heat from friction, causing immediate damage that leads to catastrophic failure.

Why Do Mechanical Seals Fail So Quickly When Running Dry

Mechanical seals fail rapidly when running dry because friction between the seal faces generates temperatures exceeding 1,000°F (538°C) within seconds. This intense heat causes the seal faces to crack, warp, or even weld together.

During normal operation, a thin film of liquid (just 0.00002 inches thick) separates the seal faces and carries away heat. When this film disappears, direct contact between the rotating and stationary faces creates immediate problems.

The damage happens in three stages. First, the temperature spikes within 2-3 seconds. Then, thermal shock causes microfractures in hard face materials like silicon carbide or tungsten carbide. Finally, the seal faces either crack completely or the softer material (usually carbon) begins to melt and deposit on the harder face.

What Factors Determine How Long a Seal Can Survive Dry Running

Seal Face materials

Seal face materials make the biggest difference in dry-running survival time. Silicon carbide against silicon carbide can handle dry conditions better than most combinations, potentially lasting 1-2 minutes at lower speeds. Carbon against ceramic or tungsten carbide typically fails within 10-20 seconds.

Shaft Speed

Shaft speed directly impacts failure time. A seal running at 3,600 RPM will fail about four times faster than one at 1,800 RPM. Higher speeds mean more friction and faster heat buildup.

System Pressure

System pressure also plays a critical role. Higher pressure forces the seal faces together more tightly, increasing friction. A seal at 150 PSI might fail twice as fast as one at 50 PSI.

Temperature

Temperature before dry running starts matters too. If the seal is already hot from normal operation, it has less thermal capacity to absorb the additional heat from dry running.

FAQs

What is the absolute minimum time a standard mechanical seal can run dry?

Most standard mechanical seals will show signs of damage within 5-10 seconds of completely dry running, with catastrophic failure typically occurring within 30 seconds under normal operating speeds and pressures.

Can adding water save a seal that’s running dry?

Adding water immediately (within the first 5 seconds) might prevent permanent damage, but the thermal shock from adding cool liquid to hot seal faces can also cause cracking, so it’s better to stop the equipment first.

What’s the difference between dry running and dead heading?

Dry running means operating without liquid at the seal faces, while dead heading means running a pump with the discharge valve closed—both can damage seals, but dry running causes failure much faster.