Mechanical seal failure is the most common cause of pump downtime. Seal failure rates exceed 85% in many facilities. That’s a brutal number.

But here’s the thing: most of these failures are preventable. And when you’re pumping hazardous chemicals, toxic fluids, or corrosive media, a single seal just doesn’t cut it.

A double mechanical seal gives you a backup. It uses two independent seals arranged in series with a barrier or buffer fluid between them. If the inner seal fails, the outer seal keeps working. No leakage to atmosphere. No environmental incident. No unplanned shutdown.

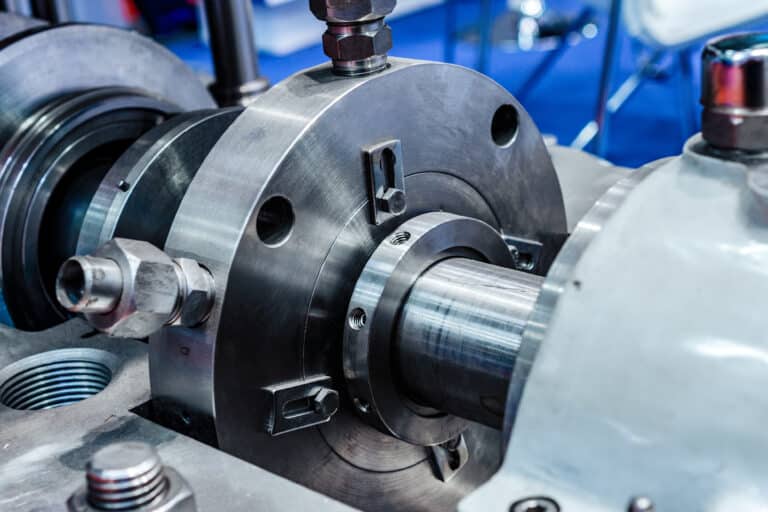

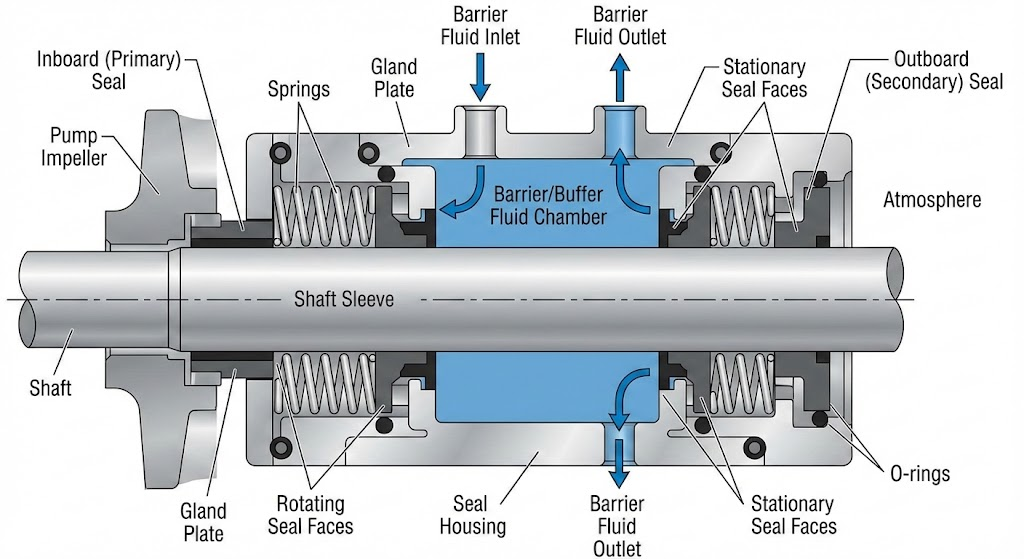

How Does a Double Mechanical Seal Work?

A double mechanical seal contains two complete sealing systems instead of one. The inner seal (called the inboard or primary seal) keeps your process fluid inside the pump. The outer seal (called the outboard or secondary seal) prevents the barrier fluid from escaping to atmosphere.

What Are the Key Components?

Every double seal has five essential elements:

- Inboard seal – contains the process fluid within the pump housing

- Outboard seal – prevents buffer or barrier fluid from leaking out

- Four seal faces – two rotating faces attached to the shaft, two stationary faces fixed to the housing

- Barrier or buffer fluid chamber – the space between the two seals filled with a clean lubricating fluid

- Spring mechanism and elastomers – provide face loading and secondary sealing

What Is the Operating Principle?

The magic happens in two stages. The inner seal creates a barrier between your process fluid and the fluid chamber. The outer seal keeps that chamber fluid from escaping to atmosphere.

Both seals rely on a thin fluid film between their faces. This film is typically only 0.25-1 micron thick. It provides hydrodynamic lubrication that prevents the faces from touching directly. Without this film, seal faces overheat and fail in under 30 seconds.

The pressure differential between the process fluid and the barrier fluid determines which direction any leakage flows. This is where the barrier vs. buffer distinction becomes critical.

What Is the Difference Between Barrier Fluid and Buffer Fluid?

The difference comes down to one word: pressure.

How Does a Pressurized Barrier System Work?

A barrier fluid runs at higher pressure than your process fluid. You maintain it 1-2 bar (15-30 PSI) above the seal chamber pressure.

This pressure difference means any leakage goes INTO the pump, not out to atmosphere. Your process fluid never reaches the outer seal faces. It never reaches the environment.

API 682 calls this Arrangement 3. The old term was “double seal” (now technically obsolete in the standard).

You’ll see these systems on pumps handling carcinogens, explosive vapors, and lethal chemicals. They deliver zero emissions when working properly. Dual unpressurized seals can achieve emissions below 50 ppm, but pressurized barriers do even better.

Common support systems include API Plan 53A (nitrogen-pressurized reservoir), Plan 53B (bladder accumulator), and Plan 54 (external pressurized loop).

How Does an Unpressurized Buffer System Work?

A buffer fluid runs at lower pressure than your process fluid. It acts as a containment system.

If the inner seal leaks, process fluid enters the buffer chamber. The outer seal prevents this contaminated buffer from reaching atmosphere. You get a warning (level change in the reservoir) before any environmental release.

API 682 calls this Arrangement 2. The old term was “tandem seal.”

Buffer systems cost less and require simpler support equipment. API Plan 52 circulates buffer fluid using a pumping ring during operation and thermosiphon effect during standstill. It’s economical and requires minimal maintenance.

The trade-off? Buffer systems don’t guarantee zero emissions. They’re not suitable for truly hazardous fluids where any atmospheric release is unacceptable.

Which Fluids Are Used as Barrier or Buffer?

Your choice depends on process compatibility and operating conditions:

- Glycol solutions – 50% ethylene glycol mixed with 50% water works for most applications. It’s the most common choice. Use uninhibited glycol only. Antifreeze with corrosion inhibitors can damage seal faces.

- Clean water – simplest option when your process tolerates water contamination

- Mineral or synthetic oils – necessary for hydrocarbon service where water isn’t compatible

- Nitrogen or air – used in dry gas seal applications on compressors

The rule is simple: your barrier fluid must be compatible with both your process media and your seal materials. Getting this wrong leads to chemical attack on elastomers or face degradation.

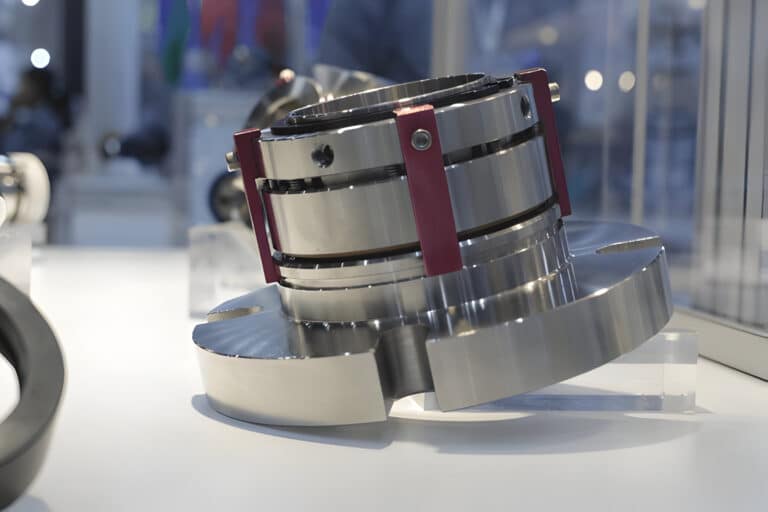

What Are the Three Double Seal Configurations?

Double seals come in three arrangements. Each has distinct advantages.

| Configuration | Description | Best Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Back-to-Back | Seal faces oriented away from each other | General hazardous fluid applications | Compact design, handles barrier pressure well | Outboard seal rated for lower pressure |

| Tandem (Face-to-Back) | Seals arranged in series, both facing same direction | Critical equipment, toxic fluids | Full-pressure backup if primary fails | Longer axial length |

| Face-to-Face | Both seal faces oriented toward each other | Space-constrained equipment | Easier installation and maintenance | Outer seal cannot provide full-pressure backup |

Back-to-back is the most common configuration in the field. I prefer it for most applications because it handles pressurized barrier systems well and doesn’t require excessive axial space.

Tandem configurations shine on critical equipment where you need absolute backup capability. If your primary seal fails, the secondary takes over at full system pressure. Oil refineries love tandem seals for this reason.

Face-to-face works when you’re retrofitting existing equipment with limited stuffing box depth. But know the limitation: that outer seal won’t hold full pressure if the inner seal fails completely.

When Should You Use a Double Mechanical Seal?

What Applications Require Double Seals?

You need a double seal when single-seal failure would cause serious consequences:

- Hazardous fluid containment – toxic, carcinogenic, or explosive fluids that must never reach atmosphere

- Corrosive service – aggressive chemicals that would destroy single seal faces quickly

- High-pressure applications – where single seals can’t handle the pressure differential

- Abrasive fluids – where you need clean barrier fluid lubricating the seal faces instead of contaminated process fluid

- Zero-emission requirements – EPA and local regulations now require emissions below 500 ppm in many areas

- Critical equipment backup – where unplanned downtime costs exceed the price of dual seal systems

A typical hydrocarbon facility with 2,500 pumps expects about 4 years MTBF (mean time between failures) for mechanical seals. Double seals can extend this significantly because the faces run on clean barrier fluid instead of contaminated process.

How Do Double Seals Compare to Single Seals?

The decision between single and double seals involves trade-offs.

| Factor | Single Seal | Double Seal |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Cost | Lower | 5-10x higher |

| Lifecycle Cost | Higher (frequent failures) | Lower (3-5 year life) |

| Complexity | Simple design | Requires support system |

| Leakage Protection | Basic | Redundant backup |

| Maintenance | Easier access | Requires barrier fluid monitoring |

| Pressure Capability | Low to medium | High |

| Space Required | Compact | Larger footprint |

| Best For | Non-hazardous fluids | Hazardous, toxic, corrosive fluids |

I’ve seen facilities switch to double seals and achieve 30% reduction in maintenance costs with 25% increase in pump uptime. The initial investment pays back in about 9 months on critical equipment.

Making the Right Choice

A double mechanical seal provides redundancy you can’t get from a single seal. It keeps hazardous fluids contained. It extends seal life by providing clean lubrication. It meets environmental regulations that single seals can’t satisfy.

The technology isn’t complicated once you understand the fundamentals. Two seals, a fluid chamber, and proper pressure management.

Choose pressurized barrier systems for zero-emission applications. Use buffer systems when you need backup protection at lower cost. Match your configuration to your space constraints and backup requirements.

Work with seal manufacturers on your specific applications. They’ve seen thousands of installations and know which configurations work best for your service conditions. That expertise is worth more than any guide.