If you work with pumps, compressors, or any rotating equipment, you’ve probably heard about mechanical seals. But do you really understand what they do and, more importantly, what those “four sealing points” everyone talks about actually are?

Here’s the thing: mechanical seals are sitting right at the intersection of complexity and simplicity. They look like a small component, but they’re doing critical work—preventing fluid from escaping your system while keeping contaminants out. And they do this through four distinct sealing points that work together as an integrated system.

What Are Mechanical Seal Sealing Points?

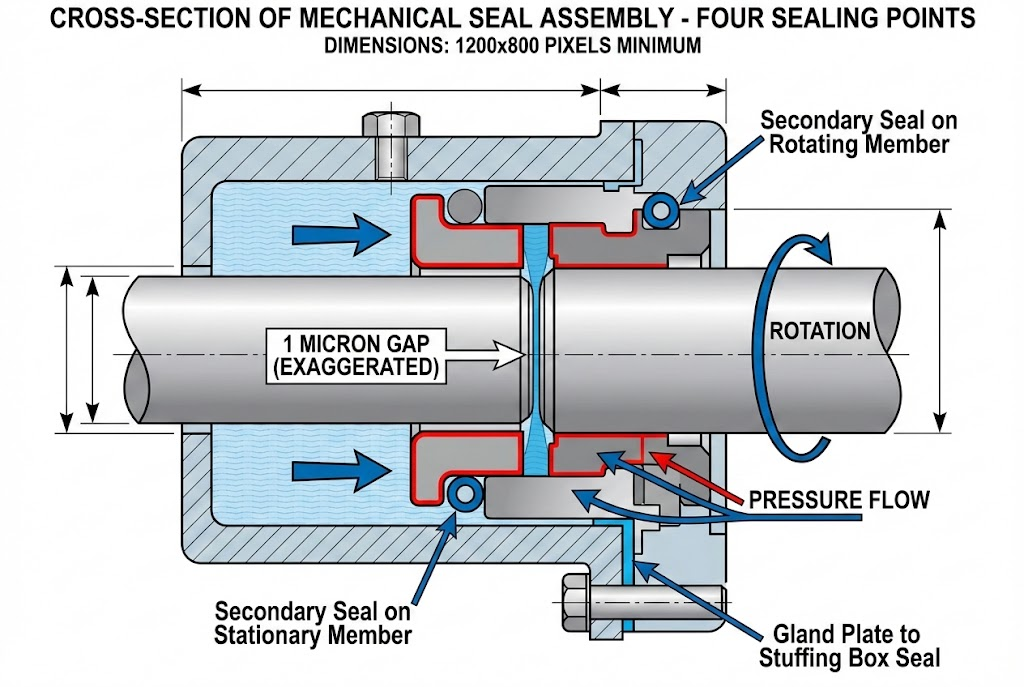

A sealing point is simply an interface—a place where two surfaces meet to create a barrier that prevents fluid from leaking. In a mechanical seal, you don’t have just one sealing point. You have four working together, each with a specific job.

Think of it like a security system. One lock isn’t enough—you need multiple layers of protection. A mechanical seal works the same way. If one sealing point fails, the others are there to catch the problem before it becomes a leak.

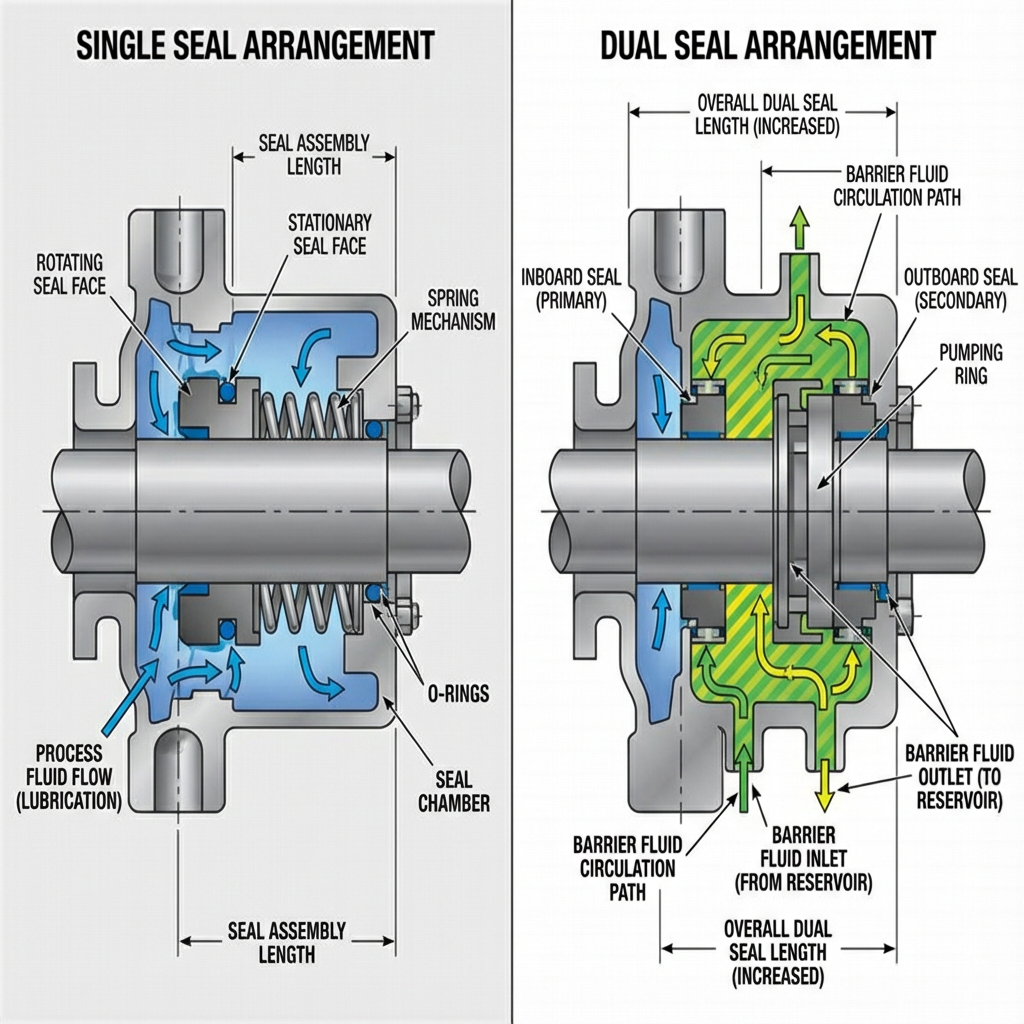

The four sealing points include one dynamic seal (where surfaces rotate relative to each other) and three static seals (where surfaces stay in place). This combination creates redundancy and ensures your system stays sealed under normal operating conditions.

The Four Critical Sealing Points Explained

Sealing Point 1: The Primary Face Seal (The Dynamic Seal)

The primary face seal is the star of the show—it’s the only dynamic sealing point in a mechanical seal. This is where the action happens.

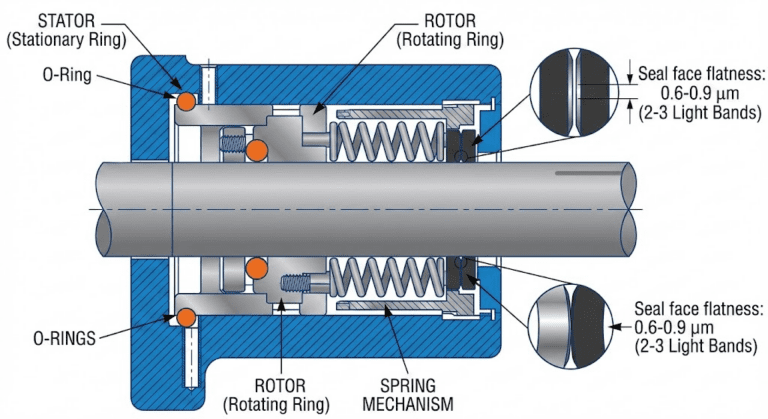

Picture two extremely flat surfaces, one rotating with your shaft and one staying stationary. These faces press tightly together, and the gap between them is incredibly small—typically just 1 micron, which is about 75 times narrower than a human hair. This tiny gap is where the magic occurs.

The rotating face spins against the stationary face, and as it rotates, it creates a hydrodynamic film—a thin layer of fluid that acts as a lubricant. This film is critical. Without it, the faces would grind against each other, generating heat and wearing out rapidly. With it, the seal can run for years with minimal wear.

The primary seal prevents process fluid from escaping along the shaft—it’s your first line of defense against leaks. When this seal works properly, almost no fluid passes through it during normal operation.

Sealing Point 2: The Secondary Seal on the Rotating Member

While the primary seal handles the main sealing job, the secondary seal on the rotating member (usually an O-ring) prevents fluid from leaking between the rotating seal ring and the shaft itself.

Think of this as a backup to your backup. The rotating seal ring needs to be attached to the shaft, but it also needs to move slightly to accommodate pressure changes and wear. An O-ring provides a flexible seal that allows this limited movement while preventing leakage.

This secondary seal sits in a groove on the rotating member and presses against the shaft. As pressure builds in the seal chamber, the O-ring gets pressed harder against the shaft, actually improving the seal. It’s a clever design that uses the process fluid itself to enhance sealing.

The secondary seal on the rotating member ensures that if the primary seal fails or allows small amounts of leakage, the fluid stays contained at this point and doesn’t escape along the rotating shaft.

Sealing Point 3: The Secondary Seal on the Stationary Member

Just as the rotating member needs a secondary seal, so does the stationary member. This sealing point sits between the stationary seal ring and the stuffing box (the housing that holds the seal).

This is a static seal—both surfaces stay in place. No rotation, no sliding action. It’s simpler in concept but equally important. A gasket or O-ring sits between these surfaces and prevents process fluid from escaping at this junction.

The stationary seal must handle the full pressure of your system without any help from movement or hydrodynamic action. It relies entirely on the compression force applied during installation and the elasticity of the sealing material.

This sealing point is your second safety barrier. It catches any fluid that somehow gets past the primary seal and the rotating secondary seal.

Sealing Point 4: The Gland Plate to Stuffing Box Seal

The final sealing point is where the gland plate (the component that holds everything in place) connects to the stuffing box. This is typically sealed with a gasket or O-ring, similar to the stationary member seal.

This external seal prevents process fluid from leaking where the gland assembly attaches to the housing. It’s the outermost barrier protecting your equipment and the environment from the process fluid.

Think of it as the outer shell of your defense system. While the other three sealing points are specifically designed for the rotating equipment, this one is protecting the external connection points.

The seal here must maintain its integrity even as the equipment vibrates and experiences pressure fluctuations. A properly installed gasket at this point virtually eliminates external leaks at the gland connection.

The Bottom Line

The four sealing points in a mechanical seal—the primary face seal, the rotating member secondary seal, the stationary member secondary seal, and the gland plate seal—work together to create a robust containment system. Understanding what each does and how they work together gives you the knowledge to select the right seal for your application, install it properly, and maintain it effectively.

Whether you’re specifying a new seal, troubleshooting an existing one, or planning a maintenance program, remember that each sealing point has a specific job. When all four are working together properly, your equipment stays sealed, your process stays clean, and your operations run smoothly. That’s the real power of understanding mechanical seal sealing points.